8. März 2015 von Britta Schneider

Kriol as a written language…

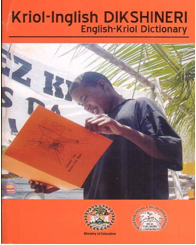

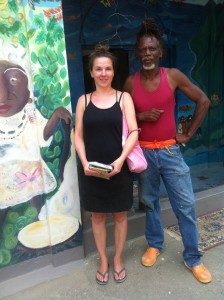

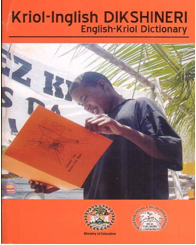

During the last weeks, I met some really interesting people – for example Silvaana Udz from the National Kriol Council. She is teaching in the education department at the University of Belize and is a language activist, striving for making Kriol a written, standard language. She and other members of the Council have developed a spelling system for Kriol and a Kriol-Inglish dikshineri.

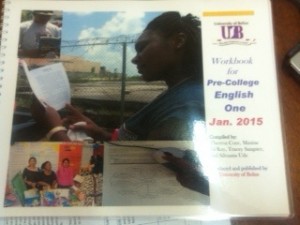

Next to supporting Kriol for strengthening Creole culture in Belize, Silvaana finds it important for improving literacy abilities of pupils in Belize. Many pupils in Belize face difficulties in English. One reason may be that the differences between English and Kriol are usually not taught systematically. Linguistic research, as well as the UNESCO, actually support native language tuition as learning to read and in a language you do not know is obviously problematic (a ‘classic’ on this is, for example, Cummins 1995, see also UNESCO 1953). Indeed, language skills do represent a problem in Belizean education. Sylvanna showed me a curriculum she developed to improve standard English language skills at university level as many students come to university whose standard English is not sufficient. Supporting literacy in Kriol thus may be a sensible idea.

… or as ‘anti-standard’ in an age of global mass communication???

I also met with Corinth Morter-Lewis, an educator who used to be the president of the University of Belize, and a writer of poetry and prose. More about her works and her person can be found here.

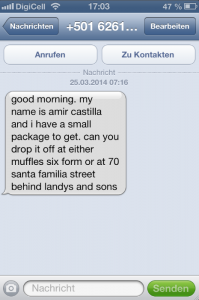

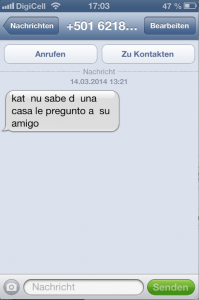

Interestingly, Corinth said that statistically, pupils’ level of standard English used to be better in the past – when there neither existed any teaching of Kriol. She suggested that a lack of exposure to standard English is one reason, as kids nowadays generally read very little but listen to radio, internet videos and TV where the boundary between English and Kriol is oftentimes not very clear. Even teachers commonly use grammatical forms that would not be regarded as ‘standard’ by people from outside of Belize. Another interesting aspect she mentioned was that pupils have started to use forms of language in class that they also use in texting and chatting – where they use a lot of non-standard and a lot of Kriol forms (see also examples from texting in my entry from 27th of January).

So it seems, firstly, that the model of what is ‘standard’ English is not very clear in Belize. Secondly, the role of standard language in general may become different in a world where oral but also written language is less regimented – as in email communication, chatting and texting – and where reading books is not often done to entertain oneself (with youtube, Netflix, facebook, and I do not know what, available even to people who have no access to a washing machine – or books, for that matter). The role of writing and literacy may become a very different one in a world where people use digital media (see also Günter 2014) and this of course impacts on the role of standard language. Corinth and I thus spoke about whether or not Kriol will ever reach the status of a standard written language in Belize, where she expressed doubts.

Actually, several of my informants here have told me that they did not like the idea of Kriol being standardised as it is the fact that there is no standard they like so much (see Romaine 2005 on similar discussions in Hawai’i). I often wondered why all kids in school seem to quickly learn Kriol, even if there parents do not know it, and why everyone told my that they love Kriol because it is ‘easy’ (I do not find it easy at all…). But maybe it is just easier to learn something if you can appropriate to your own needs, without official institutions telling you what is ‘right’ and what is ‘wrong’? Without wanting to suggest that any Kriol will be considered ‘cool’ or ‘authentic’ in a local context, maybe the idea of a non-standardised Kriol is very inclusive?

Cummins, Jim. 1995. „The Discourse of Disinformation: The Debate on Bilingual Education and Language Rights in the United States.“ In: Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove and Robert Phillipson, Linguistic Human Rigths. Overcoming Linguistic Discrimination. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 159-177.

Günther, Markus: „Nur noch Analphabeten“, Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung – FAS, 25. Mai 2014, S. 2

Romaine, Suzanne. 2005. „Orthographic Practices in the Standardization of Pidgins and Creoles: Pidgin in Hawai’i as Anti-Language and Anti-Standard.“ In: Mühleisen, Susanne, Creole Language in Creole Literatures. Special Issue of Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 20. 101–140.

UNESCO. 1953. The Use of Vernacular Languages in Education. Paris: Unesco.

Die

Die