Wer genau ist Arnika und warum beschäftigt sich die Forschung mit ihr?

Who exactly is Arnica, and what is its interest for research?

Ein Pflanzenleben

Arnika gehört zu den Korbblütengewächsen / Asteraceae, also zum selben „Pflanzen-Clan“ wie Sonnenblume, Gänseblümchen, Löwenzahn oder Chicorée. Unter diesen sticht sie jedoch hervor: Im Gegensatz zu den meisten ihrer Verwandten wachsen ihre Blätter nicht einzeln, sondern stehen sich immer paarweise (selten zu dritt) gegenüber. Die meisten Blätter bildet sie direkt über dem Boden in einer Blattrosette und nur wenige an den Stängeln, die sie ausschließlich dann hervor bringt, wenn sie blühen will. Nach ihrer Blütezeit von Juni bis August sterben die Stängel ab. Auch die Rosettenblätter verwelken im Herbst, sodass nur die unterirdischen Pflanzenteile von einem Jahr zum nächsten überleben – mit Knospen für den nächsten Frühling.

The life and times of Arnica

Arnica is part of the sunflower family / Asteraceae – that is the same „clan“ of plants to which also daisies, dandelions or chicory belong. Yet among these, it sticks out: in contrast to most of its relatives, its leaves do not grow singly, but always in pairs (rarely triplets) opposite each other. It forms most leaves directly on top of the soil in a leaf rosette, and only few along the stalks it only produces when it wants to flower. After its flowering time from June to August, the stalks die back. Since the rosette leaves wither as well, only the underground plant parts survive from one year to the next – with buds for the next spring.

end of the year

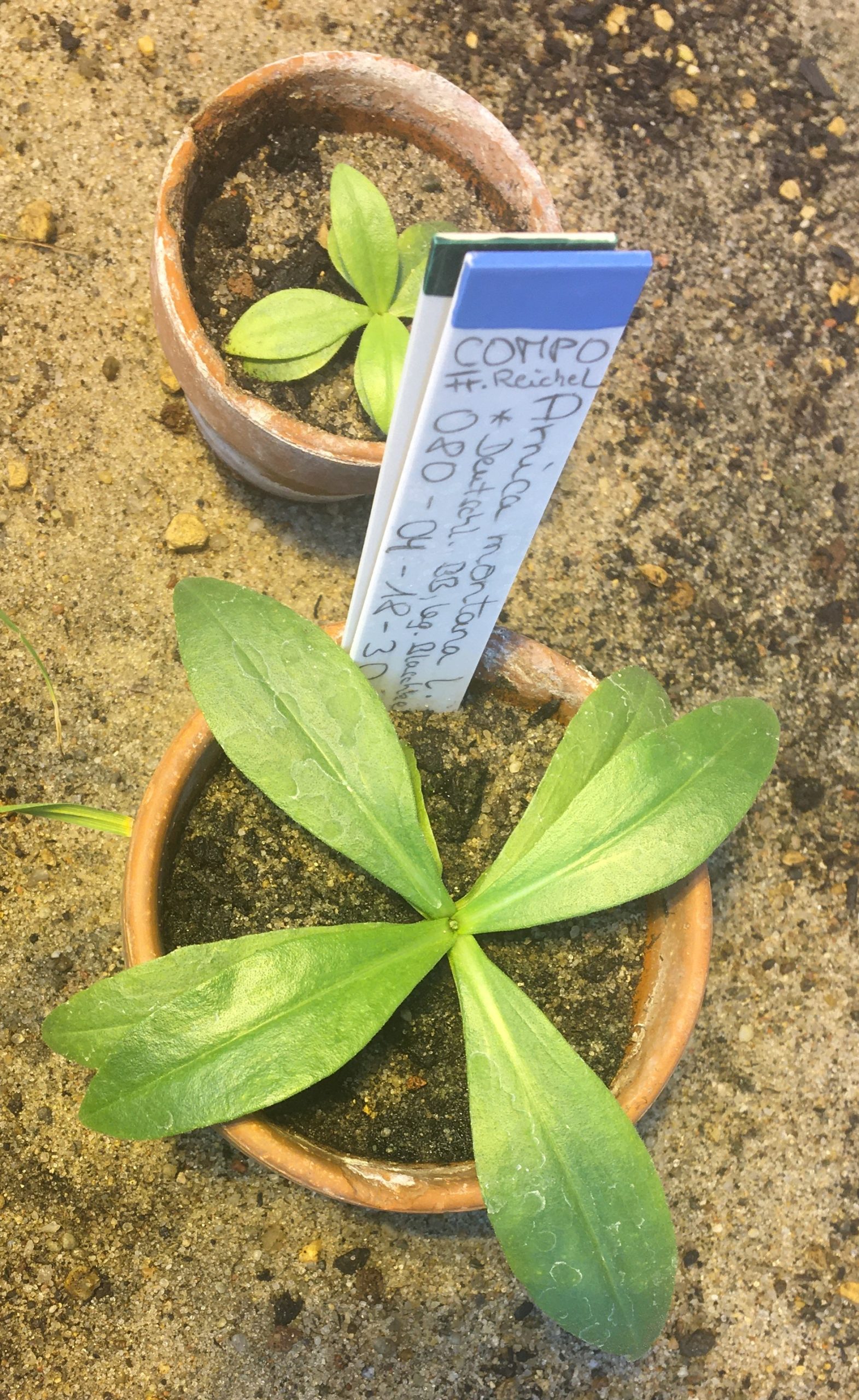

seedlings

leaf rosettes

leaves

flowerhead buds

all pollinated?

from flower to fruit

in the greenhouse

Blütenköpfe

Die sonnengelben Arnika-Blütenköpfe wirken zwar wie eine einzelne Blüte, bestehen aber – ähnlich wie die Facetten-Augen einer Fliege – aus ganz vielen Einzelblüten. Werden diese von Insekten bestäubt, dann entsteht aus jedem einzelnen Blütchen eine winzige, harte braune Frucht. Genau wie beim Löwenzahn („Pusteblume“) hat diese Frucht ein Schirmchen, mit dem es sich vom Wind wegtragen lässt – nur ist dessen Stiel bei der Arnika so kurz, dass der Schirm eher ein Haarkranz ist. Landet die Frucht an einer günstigen Stelle, kann sie im nächsten Frühling auskeimen und es sich am neuen Wuchsort gemütlich machen.

Als Schutz gegen knabbernde Tiere enthalten Arnika-Blütenköpfe eine hohe Konzentration des Giftstoffes Helenalin. In geringer Dosis und als Salbe aufgetragen wirkt diese Substanz bei Säugetieren wie uns Menschen jedoch entzündungshemmend. Das ist zwar gut für uns, aber schlecht für die Arnika, die keine schwebenden Früchte mehr bilden kann, wenn wir ihre Blütenköpfe abschneiden und zu Medizin verarbeiten. Das „Ernten“ von wilder Arnika für die Arzneiherstellung ist deshalb europaweit verboten – nur bei speziell dafür angebauten Pflanzen oder bei besonders großen Vorkommen, für die eine Sondergenehmigung erteilt wurde, ist es noch erlaubt.

Flowerheads

Though the sunny yellow Arnica heads appear to be just single flowers, they really consist of multiple small florets, much like the facet eyes of a fly. If pollinated by an insect, each floret can form a single tiny, hard brown fruit. Just as in dandelion, these fruits have tiny umbrella-like parachutes, which can be picked up by a gust of wind to carry the fruit away – except that the Arnica’s umbrella lacks a handle and looks more like a crown of bristles. If the fruit lands in a suitable place, it can germinate in the next spring and get settled down at its new home.

As a protection against peckish animals, Arnica flowerheads contain the poison helenalin. In a low dose and applied externally as a cream, this substance does, however, soothe inflammations in mammals, including humans. What’s good for us is now bad for Arnica, since it cannot form its flying fruits anymore if we cut off its flowerheads for medicine. „Harvesting“ wild Arnica is therefore prohibited throughout Europe – only for cultivated plants or at exceptionally large stands, for which a special licence has been obtained, it is still permitted.

[Karte Rückgang Arnika]

Verlust

In den letzten Jahrzehnten ist die Anzahl der Arnika-Vorkommen in Europa immer weiter zurück gegangen. Am häufigsten findet man sie noch in den Bergen, wo sie weit weniger von der Intensivierung der landwirtschaftlichen Praxis (z.B. durch Umwandlung von Wiesen- und Weide- in Ackerfläche, Entwässerung von Feuchtwiesen, stärkere Düngung) betroffen ist. Auch der Klimawandel mit extrem trockenen Sommern und immer zeitigerem Frühlingsbeginn, durch den anderen Pflanzen einen Vorsprung bekommen, könnte eine Rolle spielen. Kommt dazu noch illegaler Blütenklau, ist es nicht mehr verwunderlich, dass viele Arnika-Populationen am Rand des Zusammenbruches stehen.

Der Verlust wäre um so schmerzlicher, als die Arnika ein Geheimnis umgibt: Auf dem Europäischen Kontinent ist die Art Arnica montana eine Waise. Ihre Verwandten aus der Gattung Arnica leben in der Nordpolarregion, in Sibirien, Japan und vor allem Nordamerika – wann und wie ist sie also hierher gekommen? Und wer sind ihre unmittelbaren Geschwister? Als gesichert gilt, dass die europäische Arnika schon vor der letzten Eiszeit hier gewesen sein muss – aber wo und wie hat sie diese überlebt? Und wirkt sich die Vorgeschichte der Art wohlmöglich heute noch auf das Überleben von Populationen aus?

Loss

Over the last decades, the number of Arnica occurrences in Europe has been steadily declining. In the mountains they are still more numerous, since there they are less heavily affected by the intensivation of agriculture (e.g. turning hay meadows and grazing land into fields, draining of wet meadows, increased fertilization). Also climate change may play a role, leading to extremely dry summers and early springs which give other plants a head start. With illegal flower theft on top, it‘s not surprising to see many Arnica populations on the brink of a breakdown.

The loss would be even greater, as Arnica is surrounded by a mystery: On the European continent, the species Arnica montana is an orphan. Its relatives from the genus Arnica live in the northern polar region, Siberia, Japan and above all North America – so when and how did it get here? And who are its closest siblings? It is certain that Arnica was already here during the last ice age – but where and how did it survive? And could the history of the species perhaps still affect the survival of populations today?

[Verbreitung Gattung Arnika]

Ein Aufruf

Arnika hilft uns — und wir helfen ihr!

Arnika ist nicht nur nützlich, wenn wir uns gerade mal wieder das Knie gestoßen haben. Sie ist auch eine schöne und spannende Pflanze, die stellvertretend für viele Organismen steht, denen wir aktuell das Leben schwer machen. Was können wir also tun, um Arnika und ihren Nachbarn zu helfen? Hier ist schon mal eine kleine Liste:

- Nachhaltige und faire Landwirtschaft fördern — indem wir saisonale, regionale und zertifizierte Produkte kaufen

- Energie und Treibhausgase sparen — um den Klimawandel zu bremsen

- Geschützte Arten in Ruhe lassen — insbesondere in extra ausgewiesenen Schutzgebieten: Die Blütenköpfe bleiben dran und mit dem Fernglas ist man der Natur auch vom Weg aus ganz nah.

- Informieren — nicht jede*r liest diesen Blog, aber alle sollten Bescheid wissen; ganz besonders diejenigen, die Macht haben um Entscheidungen zu treffen

Und können wir die Arnika nicht auch in unsere Gärten holen, oder ihre Früchtchen mitnehmen und gezielt in die Landschaft streuen? Die Antwort ist ein klares “Jein“: Wenn wir unkontrolliert Früchte aus ohnehin schon kleinen Populationen wegnehmen und sie an Orte bringen, wo sich die Pflanzen wahrscheinlich nicht wohl fühlen, erweisen wir ihnen einen Bärendienst. Deshalb gibt es wissenschaftlich begleitete Projekte zum Erhalt und zur Wiederansiedelung seltener und bedrohter Arten, die man als Mitglied in lokalen Naturschutzvereinen aktiv unterstützen kann. Und natürlich Forschungsprojekte wie das unsere, mit denen wir grundlegend verstehen wollen, welche natürlichen Wege Arnika und andere Pflanzen zum Überleben in schlechten Zeiten nutzen und wie wir diese fördern können!

A call for action

Arnica helps us — let‘s help Arnica!

Arnica is not only useful when we have hit our knee yet another time. It is also a beautiful and intriguing plant, which stands as a model for many organisms whose lives we currently make very tough. So what can we do to help Arnica and its neighbours? Let’s have a short list:

- Support sustainable and fair agriculture — by buying seasonal, regional and certified products

- Save energy and greenhouse gasses — to slow down climate change

- Leave protected species in peace — especially in protected areas: the flowerheads stay on, and with binoculars we can also get close to nature while staying on the path

- Inform — not everyone reads this blog, but everybody should know what‘s going on; especially those with the power to make decisions

And can‘t we take Arnica into our gardens, or collect their small fruitlets to sow them out somewhere in the landscape? Well, yes and no: If we just randomly remove fruits from populations which are already small, and put them some place the plants probably won’t like to live in, we risk doing them a great disservice. This is just why there are scientifically coordinated protection and restoration projects for rare and threatended species, which we can support by becoming active members of local nature conservation societies. And there are also research projects like ours, by which we aim to get a deeper understanding of how Arnica and other plants cope with hard times in nature, and what we can do to support them in this!