- Oktober 2023 von Thomas Peeters

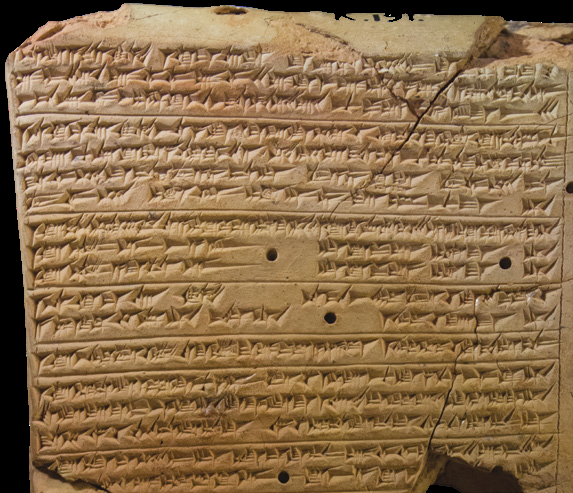

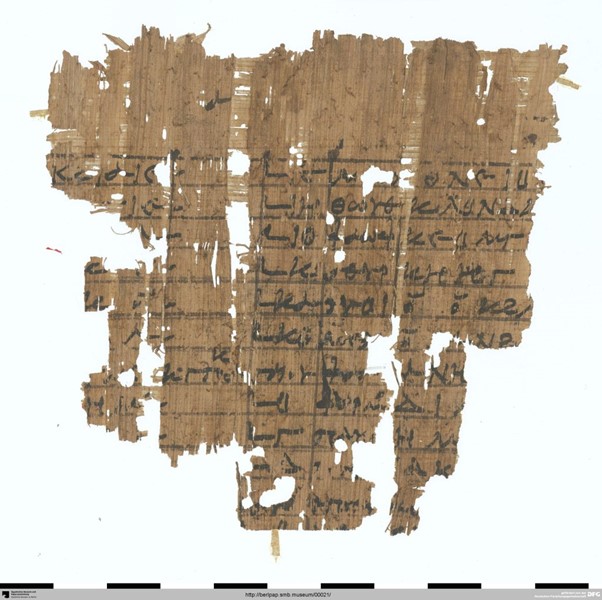

P. 16511 V

Wer heute die genaue Position von Sternen oder Planeten am Himmel bestimmen will, öffnet seinen Computer und findet mit ein paar Klicks in moderner Software alles, was er sucht. In der Antike war das ein wenig schwieriger. Astronomische Daten wurden zunächst genutzt um das Schicksal von Königen und Reichen zu bestimmen, später auch für die Erstellung von Horoskopen für Einzelpersonen. Auch in die Berliner Papyrussammlung sind mehrere Horoskope erhalten (siehe z.B. das älteste erhaltene, griechische Horoskop auf Papyrus).

Der Philosoph Sextus Empiricus (2. Jh. n. Chr.) hat in seinem Werk Πρὸς ἀστρολόγους „Gegen die Astrologen“ (26-28) beschrieben, wie die Babylonier die Beobachtung der Planetenpositionen bei der Geburt eines Kindes durchführten. Ein Astronom saß auf einer Bergkuppe, während ein Assistent neben der Frau in den Wehen saß. Wenn die Entbindung stattfand, läutete der Assistent einen Gong und der Astronom notierte sofort alle relevanten Beobachtungsdaten. Dies ist eine recht fantasievolle Geschichte, welche jedoch nicht der Realität entspricht. Beobachtungen waren oft nicht möglich: nicht alle Planeten sind immer sichtbar. Deswegen verwendete man Algorithmen, um astronomische Tabellen zu erstellen. Die Positionen in den Horoskopen wurden dann anhand der Tabellen berechnet.

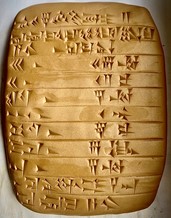

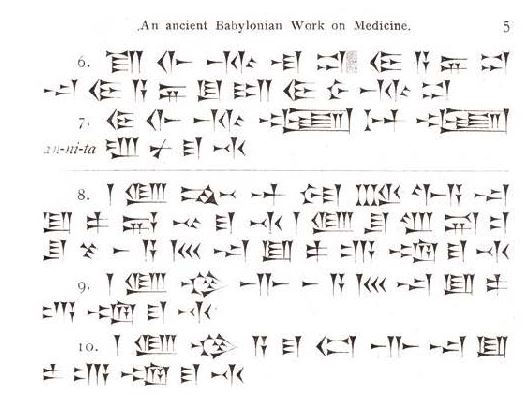

Auf dem hier vorgestellten Objekt, einem Papyrus aus Oxyrhynchus im griechisch-römischen Ägypten, findet sich ein Teil einer solchen Tabelle. Das Fragment besteht aus fünf Spalten mit schwarzen Linien und ist in einer kleinen, schnellen, kursiven dokumentarischen Schrift aus dem 1. Jh. n. Chr. geschrieben.[1] Die Tabelle ist an der linken, unteren und rechten Seite abgebrochen; der obere Teil ist jedoch vollständig. Ein zweites Fragment der gleichen Tabelle, das aus Teilen der Spalten 3, 4 und 5 besteht, befindet sich in Oxford. Auf der anderen Seite, der Vorderseite des Papyrus, befindet sich ein Gerichtsverfahren. Nachdem dieses nicht mehr relevant war, wurde auf der Rückseite diese astronomische Tabelle geschrieben, bis auch sie nicht mehr notwendig war und weggeworfen wurde. Wie alle Papyri aus Oxyrhynchus, stammt der Papyrus von einer Mülldeponie.

P. 16511 V: Astronomische Tafel, https://berlpap.smb.museum/00021/

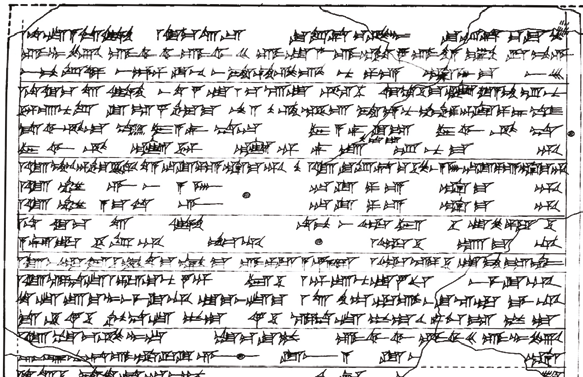

Die dritte Spalte besteht aus Jahreszahlen, die durch das griechische L-förmige ἔτος („Jahr“)-Zeichen zusammen mit einer Zahl dargestellt werden. Die Jahreszahlen erhöhen sich in der Regel um 1, manchmal aber auch um 2. So finden wir in den ersten vier Zeilen die Jahre ιϛ, ιη, ιθ, κ: 16, 18, 19, 20. Dies sind Regierungsjahre römischer Kaiser, und in Zeile 7 wird auch klar, welcher Kaiser. Hier steht in Spalte 3 keine Jahreszahl, sondern nur Γαίου, und in Spalte 2 noch zur Verdeutlichung κγ το κ(αὶ) α, was zusammen „23, auch 1 von Gaius“ bedeutet. Es geht hier um das Jahr 23 des Kaisers Tiberius, 37 n. Chr., was auch das Jahr 1 des Kaisers Gaius (Caligula) ist. Der Rest der zweiten Spalte besteht nur aus horizontalen Strichen und soll offenbar die Spalte 1 von den anderen Spalten trennen.[2]

Spalte 4 enthält ägyptische Monatsnamen in griechischer Schrift, mit vollständigen Schreibungen für kurze Namen wie Θωύθ „Thouth“ (Zeile 2), Ἁθύρ „Hathyr“ (Zeile 4) und Τῦβι „Tybi“ (Zeile 5); sowie abgekürzten für längere Namen wie Φαῶφ „Phaoph“ für Φαῶφι „Phaophi“ (Zeile 3), und Φαρμο „Pharmo“ für Φαρμοῦθι „Pharmouthi“ (Zeile 8). Das ο von Φαρμο ist dabei hochgestellt, um zu betonen, dass es sich um eine Abkürzung handelt.

In Spalte 5 steht immer erst eine Zahl zwischen 0 und 29, dann noch eine oder oft auch mehrere Zahlen. Diese geben die Tage des Monats an, mit anschließenden Brüchen dieser Tage im babylonischen Sexagesimalsystem. Dies ist eindeutig die Folge einer Berechnung und zeigt bereits, dass wir es nicht mit einer rein ägyptischen Tabelle zu tun haben. Ungewöhnlich ist auch die Verwendung des Tages 0, anstelle des Tages 30 des Vormonats, in den Zeilen 5 und 6.

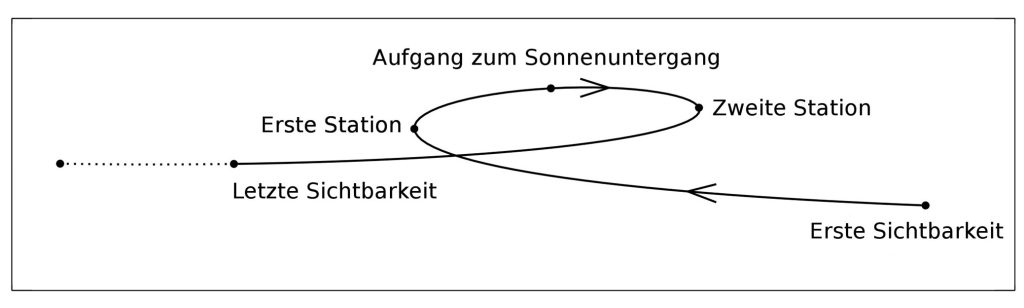

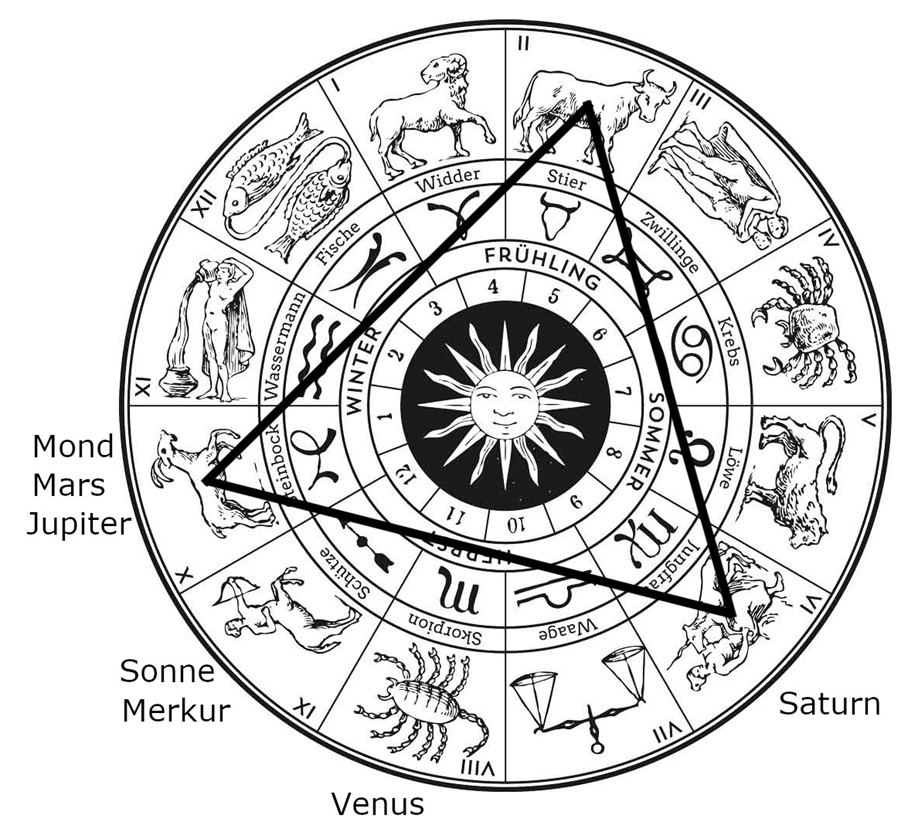

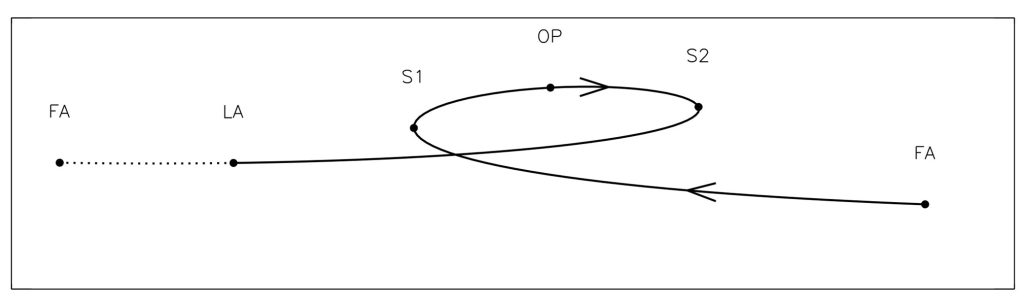

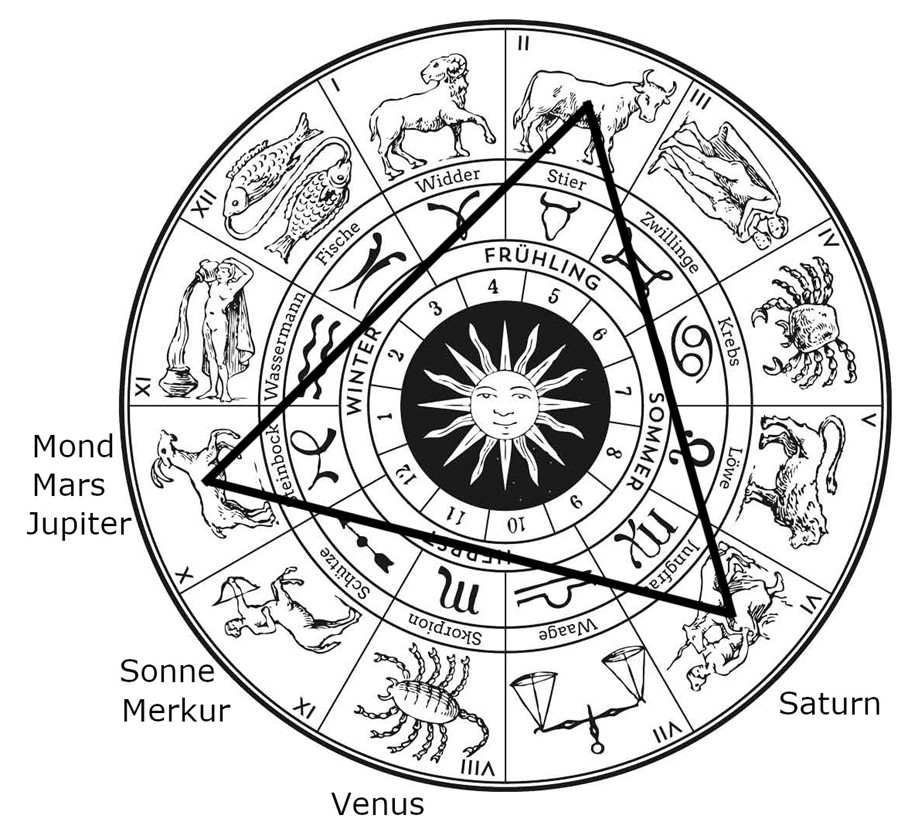

Zusammengefasst enthält jede Zeile einen Zeitpunkt, mit Zeitsprüngen von jeweils circa 13 Monaten. Diese Zeitspanne ist charakteristisch für den Planeten Jupiter, und die Analyse anhand moderner Daten zeigt, dass es sich um Zeitpunkte handelt, in denen sich Jupiter an der so genannten ersten Station befindet: dem Ort, an dem die Bewegung des Planeten rückläufig wird. Der Buchstabe α über der Tabelle könnte für die Zahl 1 stehen und sich somit darauf beziehen, diese Interpretation ist jedoch unsicher.[3] Interessanterweise war für astronomische Berechnungen noch lange Zeit der unreformierte ägyptische Kalender in Gebrauch, d. h. ohne Schalttage, da es einfacher war mit diesem Kalender zu rechnen. Im täglichen Leben war der reformierte ägyptische Kalender bereits seit anderthalb Jahrhunderten in Gebrauch, als dieser Papyrus verfasst wurde.

Die meiste Tabellen dieser Art enthielten neben den Zeitpunkten auch die entsprechenden Positionen der Planeten, ausgedrückt im zodiakalen Koordinatensystem. Diese waren vermutlich in Spalte 6 und den folgenden enthalten. Was stand aber in der ersten Spalte? Es sind deutlich Zahlen, aber da der Anfang abgebrochen ist und es sich hauptsächlich um Bruchzahlen handelt, ist es schwierig, daraus eine Schlussfolgerung zu ziehen. Es könnte sich um Himmelspositionen eines anderen Jupiterphänomens handeln, oder vielleicht um Positionen desselben Phänomens, aber vor dem Jahr 16 des Tiberius. Dass die Tabelle willkürlich mit dem Jahr 16 beginnt, ohne den Namen Tiberius zu erwähnen, spricht für die Hypothese, dass vielleicht etwas anderes vorausging.

Es war erstaunlich, mit babylonischen Methoden erstellte Tabellen in Ägypten zu finden. Die Übertragung der babylonischen Algorithmen auf Ägypten ist nicht trivial: Die komplizierten babylonischen Algorithmen mussten an den ägyptischen Kalender angepasst werden, und für die Himmelspositionen mussten aufgrund der veränderten geographischen Lage lokale Beobachtungen herangezogen werden. Dies zeigt, dass es in Ägypten fortgeschrittene Kenntnisse von babylonischen Algorithmen gab. Die Tabelle ist außerdem erstaunlich genau: das Datum weicht nie mehr als 2 Tage vom Phänomen ab, während man Jupiter bei Beobachtung bis ungefähr 10 Tage vor oder nach dem berechneten Zeitpunkt sehen kann.[4]

Literatur

Brashear, W.M. & Jones, A., 1999. An Astronomical Table Containing Jupiter’s Synodic Phenomena, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 125: 206-210.

Jones, A. (ed.), 1999. Astronomical papyri from Oxyrhynchus (P. Oxy. 4133-4300a), Volumes I, 145-148, and II, 88-91. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Britton, J. P., & Jones, A., 2000. A New Babylonian Planetary Model in a Greek Source, Archive for History of Exact Sciences 54/4: 349-373.

[1] Brashear & Jones (1999), 206.

[2] Britton & Jones (2000), 350.

[3] Britton & Jones (2000), 350.

[4] Britton & Jones (2000), 370.

Dieser Beitrag wurde zuerst auf der Webseite von BerlPap – Berliner Papyrusdatenbank unter „Stück des Monats“veröffentlicht.