Tagesspiegelbeilage vom 02.07.2022

Das Institut für Wissensgeschichte des Altertums wird neue Aspekte des menschlichen Wissens in der Antike ausleuchten: Das Projekt „Zodiac“ erforscht die Erfindung des Tierkreises durch die Babylonier

Ist es irreführend zu fragen, ob die Einweihung eines neuen Instituts an der Freien Universität unter einem glücklichen Stern stand? Am 17. Juni 2022 geboren, hat das Institut für Wissensgeschichte des Altertums das Sternzeichen Zwilling mit Aszendent Jungfrau. Dass zum Zeitpunkt seiner Eröffnung, um 11 Uhr, die Sonne im 9. Haus und der Merkur im 8. Haus stand, deutet darauf hin, dass das Institut besonders neugierig und darauf ausgerichtet sein könnte, seine Mitmenschen zu verstehen. Jupiter im 6. Haus spricht dafür, dass es hohe Standards im beruflichen Umgang mit anderen beachten und einfordern wird.

Wissenschaft oder Aberglaube?

Nun man kann derlei Vorhersagen und Horoskopie als Aberglauben abtun. Tatsächlich aber gehen all ihre Bestandteile – der Tierkreis (lat. zodiacus, von griechisch zodiakós), die Sternzeichen, die astronomische Berechnung der Planetenpositionen und die astrologische Interpretation des Ganzen – auf eine wissenschaftliche und kulturelle Revolution zurück, die in genau diesem Institut für Wissensgeschichte des Altertums in Zukunft unter anderem erforscht und gedeutet werden soll.

Der Wissenschaftshistoriker Professor Mathieu Ossendrijver wird eben diesen „zodiacal turn“, der sich im antiken Babylonien vor 2500 Jahren, also um 500 vor Christus, vollzogen hat, als Leiter des im neuen Institut angesiedelten Forschungsprojekts „ZODIAC – Ancient Astral Science in Transformation“ während der kommenden fünf Jahre erforschen.

Matthieu Ossendrijver ist nicht nur Althistoriker und Assyriologe, sondern auch Astrophysiker. Das ist insofern von Vorteil, als das ZODIAC-Projekt sich mit der Geburt der babylonischen Astralwissenschaft, also der Horoskopie, beschäftigen will.

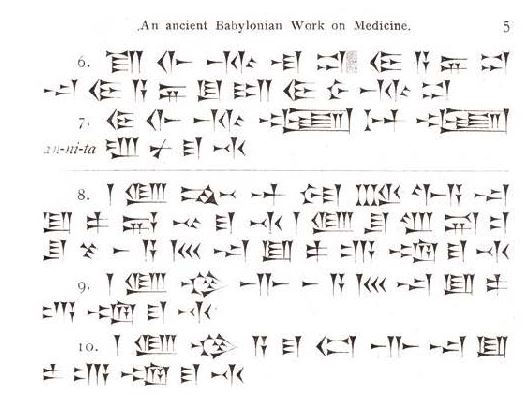

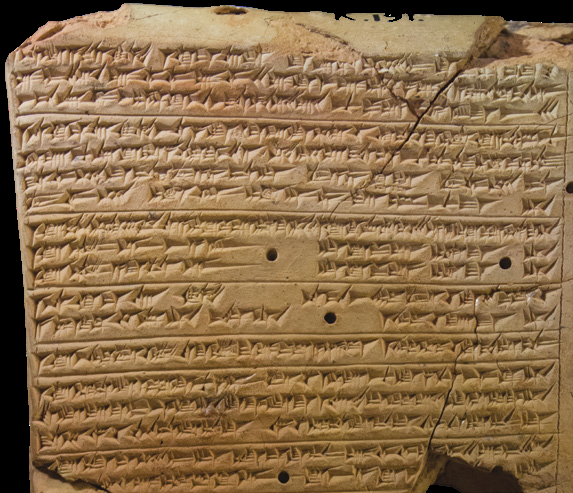

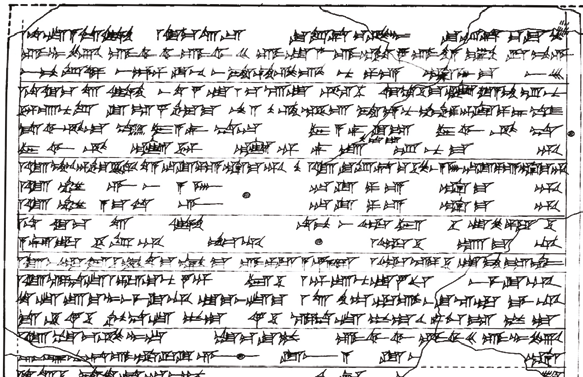

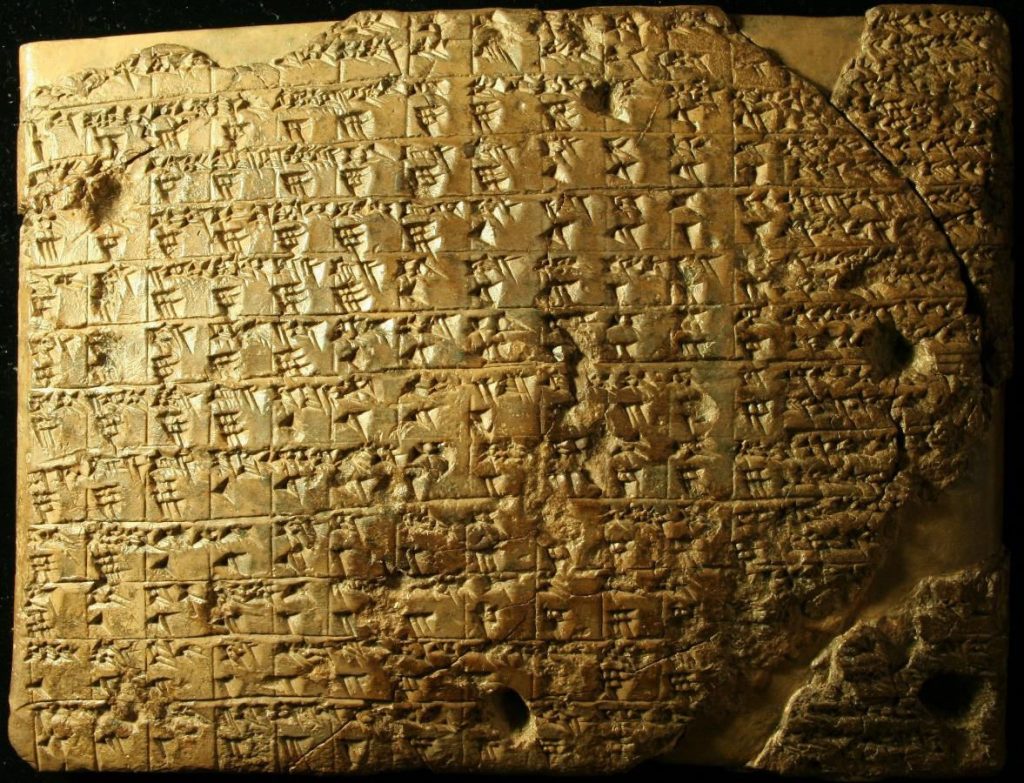

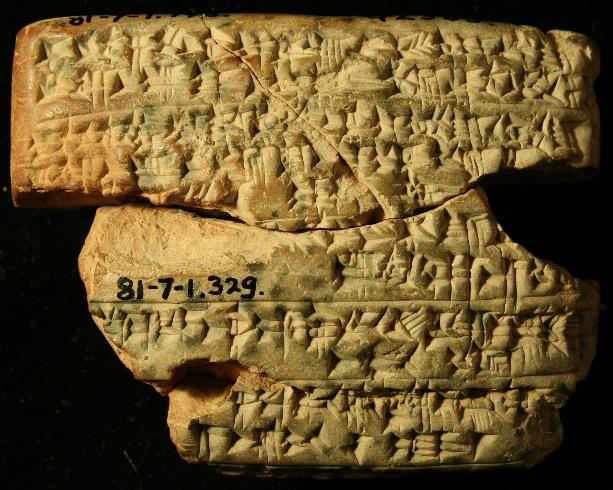

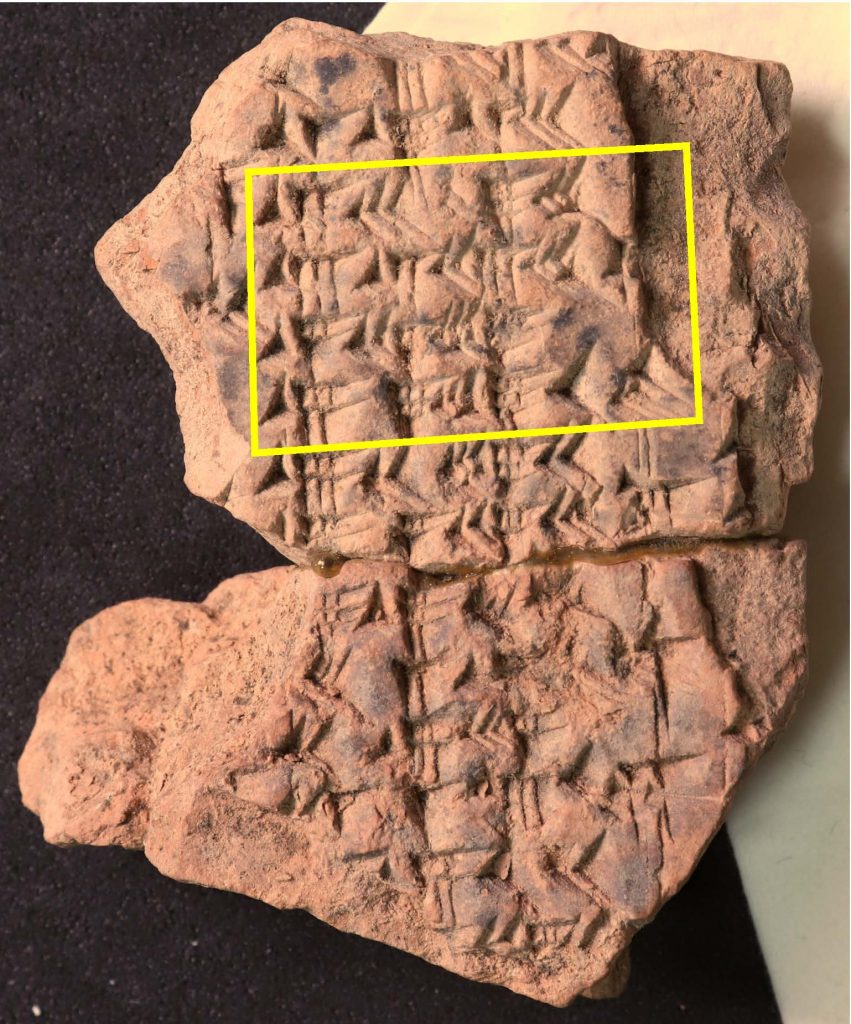

Matthieu Ossendrijver nennt mehrere Elemente, die zusammenkommen mussten, damit die Babylonier die Sternzeichen und das Horoskop erfinden konnten: Erstens hatten sie schon über lange Zeit die Bewegungen der Himmelskörper, der Sterne und Planeten, beobachtet, aufgezeichnet und darin Regelmäßigkeiten und Muster erkannt. Zweitens entwickelten die Babylonier über die bloße empirische Beobachtung hinaus mathematische Techniken und Werkzeuge, mit deren Hilfe sie die Bahnen der Planeten und Sterne mathematisch berechnen und vorhersagen konnten. Ossendrijver nennt das den „mathematical turn“, der Teil des „zodiacal turn“ gewesen sei.

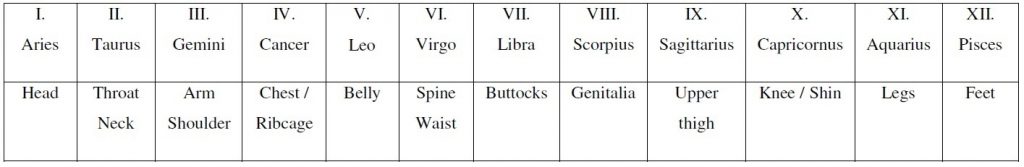

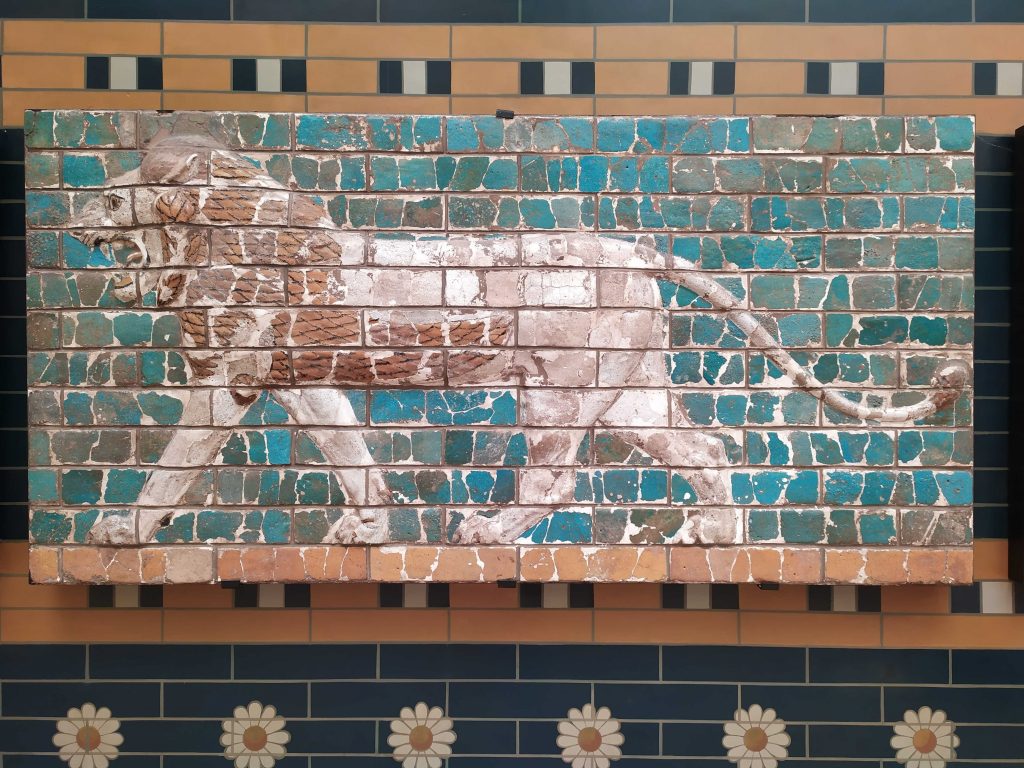

Erst dann wird verständlich, welche Bedeutung die Erfindung des Tierkreises vor 2500 Jahren hatte: Die Babylonier teilten nun den Himmel in zwölf Bereiche auf, denen jeweils eine Figur, ein Name und eine bestimmte Bedeutung zugeordnet wurde: den Tierkreis mit seinen zwölf Sternzeichen wie Widder, Zwilling, Jungfrau oder Löwe.

Bildquelle: Lorenz Brandtner

Schließlich verbanden die babylonischen Astralwissenschaftler diese zu einem Wissenskorpus, aufgrund dessen Berechnungen, zu welchem Zeitpunkt welche Planeten wo im Tierkreis standen, Bedeutungen und Bedeutungszusammenhänge formuliert werden konnten.

Doch was ist eigentlich der Tierkreis, den die Babylonier erfanden und der bis heute in Zeitschriften als Grundlage für Horoskope dient? „Eigentlich handelt es sich dabei um ein Band, einen Himmelsstreifen, der den Bereich ein paar Grad unter und ein paar Grad über der scheinbaren Sonnenbahn und den scheinbaren Mond und Planetenbahnen umfasst“, sagt Matthieu Ossendrijver. „Mit dem freien Auge ist der Tierkreis nicht zu sehen: Vielmehr erfanden die Babylonier eine mathematische Konstruktion, die sie nun in zwölf Teile zu jeweils 30 Grad einteilten, und bei der sie jeden Abschnitt nach dem in ihm markanten Sternbild benannten.“

Erst durch diese Art der berechnenden Astrologie, die etwa die Sonne im 8. und den Saturn im 5. Haus verortet, kann darüber gerätselt werden, was das für ein Kind – oder ein Institut – bedeutet, das an diesem Tag das Licht der Welt erblickt.

Wie hielt sich die Deutung alter babylonischer Zeichen bis heute?

„Für die Babylonier waren die Sterne und die Himmelsphänomene göttliche Zeichen an die Menschen“, erläutert Mathieu Ossendrijver. Die Stellung der Planeten bei der Geburt eines Kindes verrät also etwas über dieses Kind. Und die Astrologie dient dazu, diese göttliche Botschaft zu entziffern und zu verstehen.

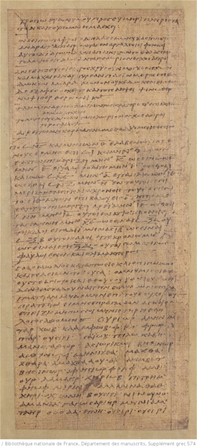

Warum aber war – und ist – die Horoskopie dermaßen erfolgreich? Wie konnte sich die babylonische Astralwissenschaft zuerst über die antike Welt ins Römische Reich, dann ins Judentum, in den Islam und ins Christentum hinein weiterverbreiten? Und sich so hartnäckig halten, dass heute noch Menschen zu Jahresbeginn ihr Horoskop studieren, um zu erfahren, ob zum Beispiel das Glück in der Liebe winkt oder ein Rückschlag im Beruf droht?

Für deren Attraktivität spricht dem Wissenschaftler zufolge, dass die Horoskopie einerseits das menschliche Bedürfnis anspricht, etwas über die eigene Zukunft zu erfahren.

Andererseits überzeugt das abstrakte System aus Zahlen und Sternbildern: Es lässt sich unabhängig von einer bestimmten Sprache, Geschichte oder Schrift sehr leicht übersetzen. Man stehe noch am Anfang, sagt Mathieu Ossendrijver, das Institut für Wissensgeschichte – unter der Leitung von J. Cale Johnson, Professor für Wissensgeschichte – ist schließlich gerade erst eröffnet worden. Aber man verrät wohl nicht zu viel, wenn man sagt: Die Antwort steht auch in den Sternen.