Looking Back on Our International Conference in Mainz, 17–20 June 2024

Katharina Wendl & Annett Martini

When we launched the organization of this conference with a call for papers last October, we were overwhelmed by the large number, high quality and, above all, the incredible thematic breadth of abstracts. It was virtually impossible for us to select only a limited number of speakers based on this rich pool of submissions. This is why we decided to turn our idea of holding one conference into two: an in-person event in Mainz and a virtual conference slated for September. At this point, we would again like to express our gratitude to all the researchers from Algeria, Azerbaijan, Brazil, Canada, Egypt, European countries, Ghana, India, Iran, Israel, Turkey, the USA and Vietnam who are involved in making these two conferences possible. Thanks to all of them, we were able to put together two incredibly rich and diverse programs.

Fast forward to four days in June 2024, which were devoted to questions about how a book, a scroll, a woodblock or an icon can become a sacred object for a particular community and how sacredness is connected to the material used for manufacturing them. What rituals are associated with these extraordinary artefacts during their production and handling? What stories are told about them and their manufacturers? What place do the materials, the script or the layout occupy in the cultural memory of religious communities or within secularized societies?

Scholars presented research on what makes books, icons, woodcuts, inscriptions, banners and sutras sacred artefacts. Some asked how narratives, rules and customs surrounding writing tools and materials have evolved. What emerged from the panels and discussions is that all these sacred objects under investigation are somehow connected to script and text respectively.

BUI THI THANH MAI (Hanoi) presented her research on ancient sacred woodblock art and how Buddhist monks of the Truc Lam-Yen Tu tradition have approached them in the light of technological advances. MOHAMMAD HOSAIN FOROUGHI (Teheran) traced the history of the Negel Qur’an, which is revered by the people of the Iranian village of Negel and beyond as a special manuscript granting blessings and security. His presentation led to discussions about the veneration of religious books, which was picked up again after presentations by CLEMENA ANTONOVA (Vienna), CORNELIA SOLDAT (Cologne) and MIGUEL GALLÉS MAGRI (Barcelona) who talked about the making, sanctification and changing purpose and meaning of icons in Orthodox Christian traditions across different centuries.

UTA LAUER (Hamburg) and RAJENDRA SINGH THAKUR (New Delhi) shared their research about Buddhist sacred literature and changing attitudes to its literary and architectural heritage. Papers on medieval English poetry as an embodiment of Christ (NATALIE JONES, London) and the highly decorative chessboard-plenarium of Otto the Mild (KRISZTINA ILKO, Cambridge), Shia Muharram banners as expressions of mourning or protest (ZEINAB VESSAL, Berkeley), and hidden numerological meanings in Ottoman culture (MUSTAFA ÖZAGAC, Istanbul) and the Sufist Hurufi sect (SLOBODAN ILIC, Nicosia) contributed to a nuanced and insightful discussion of sacredness in religious texts beyond genres that are commonly considered sacred.

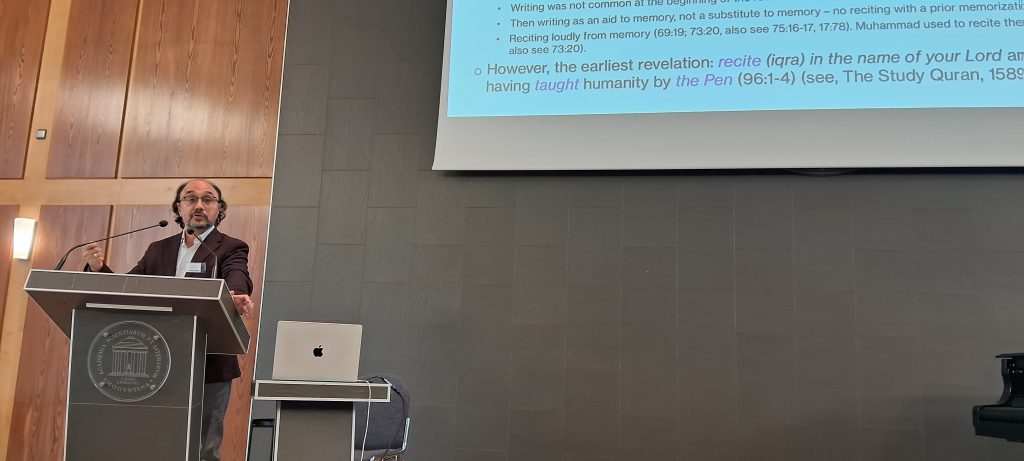

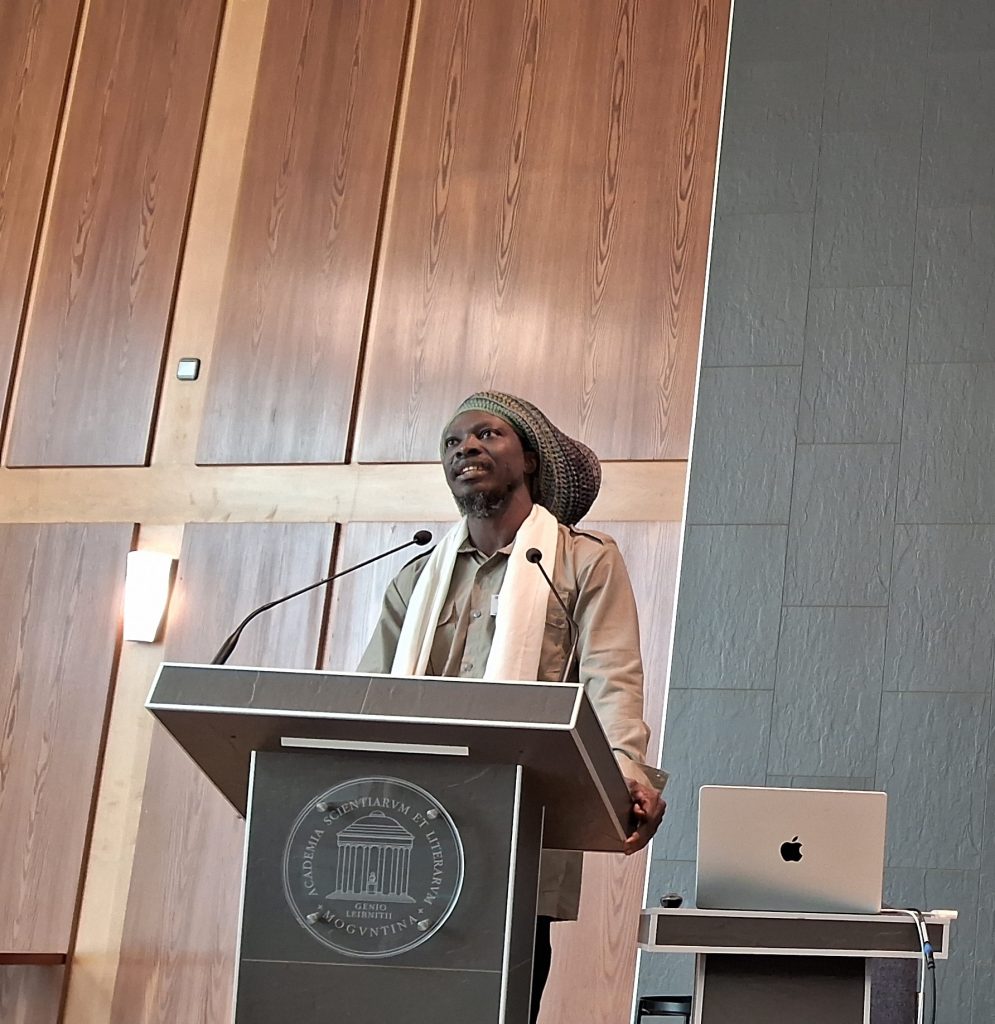

Holiness, however, is not only found in the written word but also in performance, liturgy and the traditions that develop around religious texts. In an insightful presentation on Zoroastrian manuscript culture, SHERVIN FARRIDNEJAD (Hamburg) showed that holiness in Zoroastrianism is not created by the act of writing, but by reciting religious texts from memory. Orality in relation to the Qur’an was the main theme of SAYED HASSAN AKHLAQ’S (Baltimore) contribution to the conference. The importance of the spoken word was also highlighted in JONATHAN ELUKIN’S (Hartford) paper on medieval oath-taking. BOSCO BANGURA (Leuven) and DE-VALERA NYM BOTCHWAY (Cape Coast) explained how Pentecostal Christians and Muslims in Ghana relate to scripture as an embodiment of holiness to be consumed by the believer (metaphorically or literally) to become one with the spiritual messages of the Bible or the Quran.

While most contributors were concerned with the richness of one religious tradition and its notions of scripture and ritual writing traditions, some also presented the results of their comparative studies. For example, HANNA TERVANOTKO (Toronto) discussed the divinatory use of scripture in the ancient Jewish and Christian traditions. HEYDAR DAVOUDI (Evanston) analysed the image of the Ark of the Covenant in Jewish and Muslim traditions. The sacred materiality of scripture is not exclusive to the scriptures themselves. In many religious traditions, their production as well as their makers must meet certain criteria and comply with various religious rules. HUSSIEN SOLIMAN (Alexandria/Cairo) and WALID GHALI (London) explored the traditions and instructions that Quranic scribes must follow and their required character traits, sparking insightful discussions that compared Islamic ritual writing rules with Jewish scribal traditions. JOANNA HOMRIGHAUSEN (Durham, NC) added perspectives on the reed, a central writing tool in Jewish scribal tradition, to this conversation. FARNAZ MASOUMZADEH (Isfahan) presented her research on the sacred letterforms in early Islamic Quranic manuscripts, highlighting the hidden meanings of individual strokes and lines in Quranic manuscripts. THOMAS RAINER (Zurich) traced the use and depiction of purple script in Christian art and biblical manuscripts. But once words deemed sacred have been written down, consecrated and used, what happens when, after many years, these sacred texts are worn out and cannot be repaired anymore? LEOR JACOBI (Ramat Gan) and NETTA SCHRAMM (Beer Sheva) discussed religious laws, customs and sensitivities regarding the disposal of Jewish ritual texts and sound recordings. While Leor Jacobi focused on medieval Spanish Jewish culture, Netta Schramm explored contemporary discussions and dilemmas facing laypeople and rabbis in dealing with Jewish texts and recordings that are in their possession and that they wish to dispose of.

The breadth and depth of the presentations were fascinating, enlightening and eye-opening. Despite the different religious traditions, time periods, media and cultures studied by each contributor, the conversations and insights gained from this interdisciplinary gathering of scholars from so many religions and cultures were, indeed, fruitful. They allowed participants to see their research in the wider context of religion, art history, intellectual history and cultural studies.

While the research project „Materialised Holiness“ focuses exclusively on Jewish notions of scribal culture, Jewish scribal traditions, and Torah scrolls, it is no surprise that such an interdisciplinary conference has been part of the project’s plans from the beginning. Torah scrolls are unique and defining to Judaism in their production, use, lore, and history, as emphasised by Prof. DAVID STERN (Cambridge, Mass.) in his keynote address „How to Make a Book Holy: The Case of the Jewish Tradition.”

However, Jewish scribal rules and narratives about writing in Jewish tradition did not develop in a vacuum. Rather, they were shaped inter alia by technological and economic developments. Moreover, they were influenced by the cultures in which the Jewish diaspora lived. The values, norms, traditions and beliefs of mainstream Christian or Muslim societies impacted Jewish traditions, too. Thus, despite all the theological and cultural differences, the meaning attributed to the act of writing and veneration of Jewish sacred texts have parallels in different religious traditions. Many rules and traditions about the painstaking manufacture, careful usage, respectful handling and dignified disposal of Torah scrolls can be linked, paralleled, and contrasted with those of other religious traditions. Therefore, comparatively studying Torah scrolls and other sacred writings can stimulate not only dialogue and mutual understanding but also new insights. It is precisely the interweaving of different cultures, the interdependence of Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist and other ritual professionals as well as lay people, that creates the rich, multifaceted practical, mystical, exegetical and philosophical traditions that imbue texts not only with religious meaning but with holiness.

The diverse and multifaceted research findings that were presented in the auditorium of the Mainz Academy of Sciences and Literature were discussed not only in the panel sessions but also during breaks, dinners and walks through the city of Mainz, for example on the way to a guided tour of the church of St. Stephan, which is adorned with glass murals designed by the artist Marc Chagall. It emerged that an interdisciplinary investigation into sacredness and religious objects, most formerly books, offers many new avenues for research, exchange and dialogue and should be the subject of future research activities.

On Wednesday evening, pianist THOMAS BÄCHLI (Berlin) added music to the conference’s diverse repertoire with a performance of Johann Sebastian Bach and John Cage. The conference was such a warm, productive, and stimulating occasion that will certainly stay with us for a long time.

After four days of constructive dialogue, it was time to say goodbye and express thanks: To the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz for hosting the conference, to the team at Freie Universität, both those who came to Mainz and those who worked in the background to make this conference possible and above all to the contributors, participants and moderators of this conference.

Some participants did not have to travel far to get to Mainz. Many others, though, had to travel across half of the globe to join us at the Academy of Sciences and Literature. In the months leading up to the conference, several scholars, in addition to preparing their papers, had to submit visa applications, attend appointments at German embassies, and hand in a dozen documents to be allowed to attend our conference. Unfortunately, two scholars were prevented from joining us in person due to bureaucratic reasons that restrict academic exchange. We hope to give them a platform for showcasing their important research in our upcoming online conference entitled “Creating More Holiness” (Sept 23-25). Seeing the difficulties that scholars from other parts of the world face in engaging in academic exchange humbled us. It also forced us to reflect on the Western privileges that come with having the ‚right‘ passport, the ‚right‘ country of residence, and being employed by the ‚right‘ academic institution.

It is hoped that the conversations initiated by Creating Holiness will continue and that this meeting in Mainz will generate collaborations, partnerships and new ideas for further research topics and questions. Our first joint project will be the publication of the articles that will grow out of the papers presented at the two conferences. We are already in talks with the publisher Brepols for this matter. Thanks to the enormous cultural diversity represented by the contributions, we hope to sharpen with this volume the phenomenological view of writing as a particular sacred activity. We also expect this collection of papers to challenge our own inherently narrow perspective on the Jewish tradition of writing. Judaism is not an island. Naturally, the diverse cultures in which Jewish diasporas have existed, have made an impact on Jewish book production – and vice versa: The Jewish understanding of what a sefer ha-qodesh should look like influenced the Christian and Muslim spheres of sacred writing. Finally, we would like to express again our thanks to the Academy of Sciences and Literature for hosting us in Mainz for this four-day conference. In addition, we very much want to thank the Federal Ministry of Education and Research for funding this conference so generously.