Commonplaces should, if possible, be avoided. Don’t preface your introduction with sentences like “English grammar has been a fascinating challenge to linguists for years” or “Speaking a language is what makes us human”. That may or may not be true, but it does not further your project at all, and such pre-beginnings become increasingly annoying the more of them you have to read.

Academic texts are not primarily meant to “sound good” — not at the cost of the contents. Don’t use words if they don’t mean what you want to say. For instance, many students overuse the word moreover, probably because they were told to connect their sentences somehow. But moreover means that what follows adds more support to an argumentation already in progress – don’t use moreover if you are going to introduce a completely new point. Another expression overused these days is delves into. If I got a Euro each time I read this in a term paper, I’d be able to invite you all out for a very nice dinner. If you do want to use it, make sure to use it correctly. Hypotheses don’t delve into things, and neither do analyses. People or texts delve into things.

Consider the logical connections in the following passage and evaluate the use of conjunctions and adverbials. How could the passage be improved?

Studies show that the frequency of use of phrasal verbs has decreased in academic genres (Kovács 2008; Leone 2021; Rodríguez-Puente 2019; Thim 2012). In addition, Thim (2012) and Rodríguez-Puente (2019) refute the assumption that phrasal verbs are informal and colloquial. Thim (2012) points out the lack of evidence for the alleged informality of phrasal verbs while Rodríguez-Puente refers to Thim's (2012) claim "that their alleged colloquial character is a mere 'conspiracy'" (Rodríguez-Puente 2019: 283), but later concludes that "phrasal verbs have a more colloquial character than their one-word Latin equivalents" (Rodríguez-Puente 2019: 283). Contrarily, Kovács' (2008) research demonstrates that phrasal verbs are neutral rather than informal. Leone (2021) further investigates the shift from using phrasal verbs to using simple verbs in court rooms. Moreover, the study shows that certain phrasal and simple verbs can be used interchangeably in the same context while others cannot. Some single-word verbs and multi-word verbs can be used interchangeably if they do not differ in meaning and usage while others cannot (Kovács 2008:9).

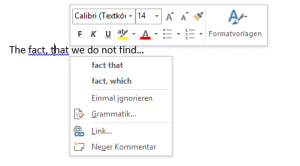

The conjunction but in the middle of the passage, and possibly contrarily two lines later, are the only one that are used well. The first sentence is about the frequency of phrasal verbs and the second sentence is about style, so connecting them with moreover is confusing. If Rodríguez-Puente (2019:283) agrees with Thim’s claim that phrasal verbs are not necessarily colloquial (it would have been better to make that clear instead of just saying that she “refers to” the claim), the sentence should not begin with while, which expresses contrast. (And if Kovács demonstrates that that phrasal verbs are neutral rather than colloquial in 2008 already, the point ought to be settled. Why do Thim and Rodríguez-Puente argue about this again later?) Saying that Leone “further” investigates the shift from using phrasal verbs to using simple verbs suggests that they investigated it before and are not following up on their previous investigation. This is probably not what is intended. Since a change in usage patterns/relative frequencies is a new point not directly connected to the style question (hence the new paragraph), there is no need to use a connector at all. The following sentence gives the results of Leone’s study; beginning it with moreover is, again, confusing, since it makes us expect a new point in support of a previously supported claim. (It does seem as if Leone’s study makes at least two very different points, but if the first sentence tells us what the study “investigates”, we assume that this is its general topic, and expect the following text to inform us about the findings.) These repeated inaccuracies make the passage difficult to read.

The problem, probably, was that the author was told to read a particular number of texts on the topic and collected bits and pieces at random before having an agenda of her own, and then tried to work unconnected pieces of information into a connected text, which resulted in cohesion without coherence. Instead of trying to incorporate as many quotations as possible, develop your own argument first and then add support or criticise other views where it makes sense in your own line of reasoning.

It is good to let your own style of writing be informed by the style of the academic publications you read. When we use language, we always work with material we hear or read, manipulate it and send it on. But don’t sacrifice sense to fluency. It’s not nice to say that a study “aims at” doing something. That suggests that it doesn’t succeed. Don’t say that just because you feel that aims at sounds good. The same goes for focuses on – don’t say that a study “focuses on” something if that something is that study’s only object of research. Just say investigates or explores. If you feel tempted to write that something “shines a light on” something, “highlights” something or “underscores” something, try to be precise instead. Does it explain something, or demonstrate something, or merely draw attention to something? And don’t overuse words like subtle and nuances. Repeated use of such terms makes your text superficial and may suggest to your reader that you were unable or unwilling to work through the details.

In general, you should always write in a goal-oriented way. You need to argue your point in a very limited number of words, so say what you have to say concisely, and use simple words if you can. The complexity of the text should not exceed the complexity of the contents. Einstein said (supposedly): “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.”