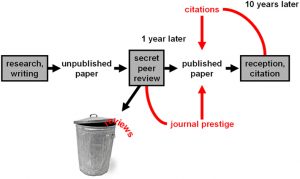

I would argue peer review is the central mechanism of subjectivation in academia – in and through participation in peer review one is created as an academic. The idea is quite simple really: by having one or two experts in the field review a text, an editor of a journal or a book evaluates the presented findings for competence, significance, and originality. Peer review is supposed to discern “good” research from “bad”. It has actually evolved along with science and was first documented for scientific findings in the 18th century (Benos et al. 2007). The idea is appealing and it sort of makes sense – let people comment, who know their stuff and make sure, that research is worth reading.

Academic excellence today is largely determined by the ability to publish work, that has undergone what is called a double blind peer review (what you have done this week, sort of). The work shall be examined without looking at the person who created it and the reviewer shall be freed to say what they believe without considering possible consequences for themselves. In a system that trades in mutual recognition that seems a reasonable way to avoid that people stray from an objective judgement of the work. The blindness of the review, ideally, makes it possible for a junior expert to challenge a seniors research without having to fear for their career. And, part of the reason we tried the double blind review now is, that one reviewer in the open peer review we did last time remarked, that they felt distracted by the fact that they actually knew the person.

By Nikolaus Kriegeskorte [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

However, recent years have seen a number of significant criticism of this system and these criticism concern all of the expected benefits. Firstly, peer review does not, in fact, prevent the publication of research that contains errors – reader discretion remains advised. that does not mean, it does not contribute to making more obvious flaws visible – but no guarantees! This is, of course, most relevant in the natural science, where the production and collection of data is central and may be reproduced. Secondly, it is usually not that blind. The more limited the number of experts in a field, the more likely it is, that one can guess who wrote the review by considering from what perspective they criticize the argument. Thirdly, peer review tends to favour those who make small innovation within the orthodoxy. Findings and approaches that are weird, “out-there” or radical have a much harder time becoming part of the mainstream. Notable cases include articles rejected by “Nature” – the leading science journal – which presented research that was later honoured with a Nobel Prize (Kilwein 1999). The reasons are simple – radically new approaches are less proven and experts are more likely to doubt their validity.

In social science this later point has another twist to it. I have been the recipient of a number of peer reviews and one thing came up again and again – reviewers saying that, since they were doing this, whatever I was doing was obviously less important and innovative but might be made into something useful if it was more like what they were doing. No kidding. Those comments are not even evil, they are honest. Obviously, I think what I do is more interesting and innovative that what other people are doing – or I would what they do! This leads to some weird results when implemented – which are best illustrated by this comic. It is fairly accurate and has brought me great enjoyment.

In order to counter these problems and regain some of the good things about peer review – like getting suggestions from other smart people on how to make the paper even better – a number of variations have emerged. They are not as recognized as the good old double-blind, but maybe there is hope yet:

Open peer review

This is what we did for the first essay. Things here are not necessarily about judgement, but more about engaging in a conversation. At least ideally. The fact, that the researchers know each others names cannot just encourage restraint in a bad sense and make them less critical. It might also make them take the whole process more seriously. I once received a paper back with a review that read – in its entirety – “This is a dull and boring paper not worthy of being published.”. I wouldn’t want to judge the truth of that statement, but it surely wasn’t what I consider an appropriate, professional response. I am all for open peer review, because I still have some questions (like: Why?).

Post-publication

The most radical break comes from abandoning the underlying principle – that publication is dependent upon peer recognition. Post-publication review means that work gets commented on after a first publication and it is left up to authors to amend their arguments as criticism arises. ScienceOpen is a platform that promotes this approach. It harnesses another essential of academic life – professional discourse. The idea is, that scientific debate will show the soundness of the arguments but that there is no argument for preventing ideas to be published. Surely, the internet has made this possible,, as cost have become a smaller factor. However, getting people to publish and review in these new and as of yet unrecognized settings is a challenge. For the most part, if you want to go somewhere, avoid any experiments such as this….

Clearly, I have an opinion on the matter. I would be interested in hearing yours – so go ahead and comment. Please, keep the anonymity of our little review process up as long as you can. I would like to use the opportunity during the next session to talk about the best ways to collect, receive and engage with comments on one’s work and this works best if you keep this “double blind”. See you Friday!

Tags: academia, review, writing

Die

Die