It sometimes feels like most of what is written in academia are proposals for funding – most of which propose research which never actually gets funded. Kind of weird, isn’t it? Empirically, proposals may not actually be the largest amount of text, but they clearly are important. More often than not, proposals decide if something gets done. This is true also for many other areas, like working in NGO’s or even within large firms. A lot is about pitching an idea to someone with the funding. Now, unfortunately, I cannot offer real funding, only an opportunity to practice. In our session on July 15th, we will be hearing a number of pitches – and three will be selected to “be funded”. This will be as fair or unfair as any such selection process – what if 5 or 8 proposals are amazing? Well, it is a good thing its only imaginary money that way. You all get to practice and feedback on your pitch. And here is, how this is going to work.

The proposal

Everyone, who wishes to receive a grade in this class, must e-mail me a PDF (!) of their research proposal by Friday 8th of July. All proposals will be uploaded to the protected section of the blog by Saturday morning. These are the basic requirements for the proposal:

- The proposal must address an issue related to the class, but may suggest empirical research related to the theories we discussed. You are not restricted to using issues addressed in the third phase.

- The proposal should outline research that could be done in a Master’s thesis or short project lasting no longer than 12 months.

- The proposal should be approx. 1500 words in its reworked version – as usual this limit applies not so strictly for now, but for the final version.

- The proposal should be structured to include the following:

- State of the Art

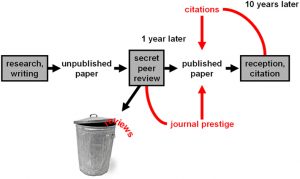

This usually describes all relevant literature of the field in question and points out the remaining deficiencies – preparing for your research questions as alleviating these. Obviously, I do NOT expect you to read everything on even the smallest possible issue. But I would ask you to do a preliminary literature review and show, where there is a gap in the literature you have read, i.e. which question remains open and why it should be answered.

This is where you convince the reader that your research is important. - Research question and method

State clearly which question you will answer and how this answer will be achieved. State any hypotheses you will have, methods that will be used and the outcomes you expect. If there is any obvious challenges, say how you wish to address them. Say, how the research will be summarised and published (Can you think of novel ways?).

This is where you convince the reader, that the research can be done. - The plan

Usually, proposals lay out a timetable for the research, as well as the finances required. Let’s suppose there is simply a fixed amount to be had and therefore no financial calculation is needed. Devote a brief section of your proposal to just a timetable. What will be done when? How long are the steps going to take? Anything happening in parallel?

This is where you convince the reader that you know what you are talking about and have the organisational skills to get it done.

- State of the Art

Don’t be discouraged if writing a proposal is difficult at first. Remember that this is an exercise and the paper we read on the 15th is only the first version of even that exercise. It takes practice – and few people get funding on the first try. In fact, funding rates are so lousy, that even seasoned professors have proposals rejected (most just don’t tell). But feedback rates in our class are amazing, so this will not be for nothing, I promise!

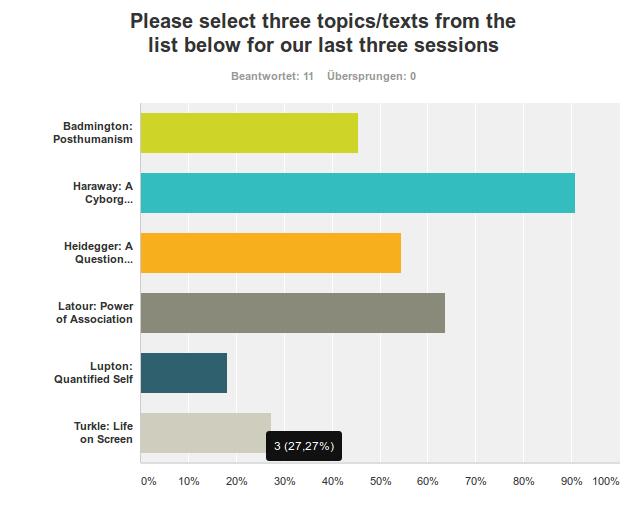

Everyone – especially those who are going for certification of participation – have from Saturday, 9th of July, to Friday morning, 15th of July, to read all proposals. Get a first impression and maybe even do a preliminary rating according to the following criteria:

- originality and relevance

- research question and literature

- demonstrated ability to complete the research (methodology and appropriate planning)

The session

Consider July 15th your big day! You get to pitch your idea to an expert committee! You will have three minutes to say:

- What makes your research important and original

- How you are going to go about completing it

- Why they should give the – imaginary – money to you

You may use presentation software, but you don’t have to. Keep in mind, that three minutes are no more than 1-2 slides in a normal presentation (some styles allow for more, but remember our time limit).

There will be three panels – I will publish next week, how they are comprised, as I will try and group them thematically. The committee will award “funding” to one proposal in each of these panels. In order to do that, committee members will be allowed to ask questions for at the most 10 minutes. After that there will be a brief 5 minute recess in which the committee makes the decision and than the result is briefly communicated and the reasons for awarding to this proposal are given by the committee. Yes, it is quick and dirty, but experience says that many longer research proposals don’t get much more consideration, either, for there is so many of them.

As usual if you have any questions, contact me! I look forward to this session.

Expect a text on posthumanism on Wednesday….

Die

Die