10. May 2016 von Ulrike

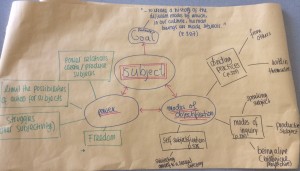

Clearly Foucault’s later writings, such as “The subject and power” and the “Technologies of the self” lend themselves more easily to an interpretation of Foucault as by no means opposed to the idea of an acting subject.* His earlier writings, which focused more on language and discourse, at first glance seem to negate such acting capacity for subjects. This aspect of Foucault’s thought may well be the most contested and has been the origin of such vibrant debate**, that it cannot be repeated here. I would like, however, to point out some of the elements of Foucault’s understanding of discourse which fuel, I believe, his later focus on the technologies of the subjects.

“Blühende Landschaften” by Thomas Kohler on Flickr (CC-BY)

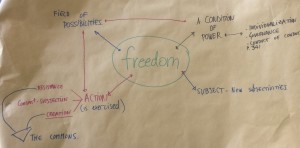

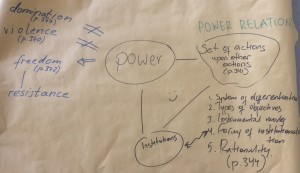

“The Order of Discourse” is the title of his inaugural lecture at the College de France held in December 1970. In it he lays out concisely (for a postmodernist, that is) the concept of discourse, which is derived from his works on the order of things and the archeaology of knowledge. Discourse therein is language, struggle and sometimes even equated to power itself. I find it easiest to imagine this discourse as a fragile network of related (speech) acts which follow and transgress rules and restrictions, somethings which changes slowly, sometimes catastrophically but never entirely. Subjects participate in discourse, reproduce it and are produced by it.

You are wondering how a discourse can even do that? Create a real living breathing thing? Aren’t we there, even if we have no name, no colour, no shape? Maybe. But we can only be who we are – living, breathing, things – in relation and through discourse. There is an episode of Star Trek, in which the Picard’s Enterprise encounters an strange alien species (ok, that’s all of them but wait for it!). This species apparently has no concept of “living” and “breathing” so that the universal translator translates their understanding of human beings as “bulky bags mostly filled with water”. While this description is technically correct, it defies the way we see ourselves. It references an entirely different discourse, hence causing irritation.

Discourse (or power) can only be noticed as the restraining, limiting and enabling phenomenon as which Foucault describes it when such irritation occurs. As discourse works through the creation of truth, which relies on differentiations, exclusions and the permanent reproduction of its own rules. Discourse hence implies an outside, a wild external to the truth discourse. This external wild side is at the same time the greatest danger to discourse. Its mere existence is proof, that the truth of the discourse is fragile. Exclusion and differentiation are the origin of dissonances. Or, as I think of it, reality is always messier than any of the ways in which we make sense of it. At the same time, if we do not make sense of it, reality has no inherent structure of its own, it cannot be perceived as reality.

What we have here, is a circular argument: Discourse produces reality (and in it subjects) and those are the source of discourse itself. None exist without the other. Many people struggle with the idea, that everything should be so fragile, preliminary and most importantly without inherent meaning or value. It is, for example, diametrically opposed to a simplified reading of Marx’s concept of history where material (!) changes and conditions drive historical change.

Even more pertinent to the question of the subject is the resulting question of how – if discourse really simply reproduces its distinctions and rules, which produce subjects which are conditioned by these restrictions and rules – discourse could ever change. Wouldn’t everything converge and remain bound by its discourse for all time, only reproducing the ever same patterns? Clearly, even this ‘early’ Foucault does not believe so. In fact, he describes the “proliferation of discourse” (in German usually translated as the ‘mushrooming’ of discourse) as a wild and chaotic process (p. 66). Yes, discourse seeks to eliminate that which does not fit, to bring order and clarity, but it fails to ever achieve this. There is an undeniable wildness about discourse over time which continuously threatens its stable continuation. And then, there is the outside, which stabilizes and threatens truth claimed by discourse.

It amazes me time and time again, how similar Arendt and Foucault argue, albeit coming from such very different places. But that is another story and must remain for another time.

*Mark Bevir has written a very thoughtful essay on the subject of agency and autonomy in Foucault’s thought.

** For first insights into the Foucault Habermas debate consider Nancy Love (1989)

Die

Die