Katharina Hadassah Wendl

One day, R. Shlomo Ganzfried (1804-1886) came across a book about Jewish scribal laws while browsing a book stall at a local market in Debrecen. He was working as a merchant throughout Eastern Hungary selling wine, but in his heart, he was a Torah scholar. He had studied under R. Zwi Hirsch Heller (1776-1834) in both Ungvar and Bonyhad during his youth, but later entered the mercantile world to sustain his family. Coming across this book changed his life quite significantly.

As his grandson R. Jechezkel Banet (1862-1913) tells in his preface to R. Ganzfried’s posthumously published Shem Shlomo (Süd-Vorahl, 1908), he found there a commentary on a few chapters of the Shulchan Arukh relevant to writing Torah scrolls called Bnei Yona (Prague, 1803). This commentary was published in 1803. It is based, though, on manuscripts by R. Yona Landsofer (1678-1712) – alive a century earlier. Slightly disorganised and more manuscript than a structured elaboration on Jewish scribal laws, this book was the only one available during his time that attempted to explain Jewish scribal laws for scribes. And it made R. Shlomo Ganzfried want to write his own.

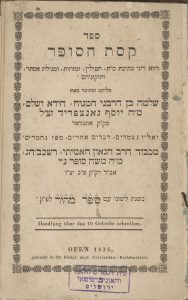

Despite not having had any formal training as a Jewish scribe himself, R. Ganzfried was determined to improve the intellectual landscape concerning halakhic scribal guides. He set out to study the laws of writing Torah scrolls, Tefillin, Mezuzot and Megillot Esther; summarising them in an accessible way for the budding scribe of the 19th century. Keset HaSofer, his very first book on Halakha published in 1835 in Ofen (Budapest), concisely and systematically presents these laws. Accompanied by an enthusiastic approbation by R. Moshe Schreiber (Chatam Sofer, 1762-1839), the leading rabbi of traditional Orthodoxy in Hungary at that time, it was highly successful. As a response, R. Ganzfried published a second, expanded edition of Keset HaSofer in 1871 (Ungvar).

Sefer Keset HaSofer. Ofen: k

önigl. ungr. Universitäts-Buchdruckerei, 1835. Cover page.

© National Library of Israel, 2023.

Within a few years, Keset HaSofer became one of the most influential books on Jewish scribal laws. And similarly, R. Ganzfried became an influential rabbinic scholar and Dayan in Ungvar and beyond. In his Keset HaSofer, he engages with a vast array of rabbinic literature, rearranges, and summarises scribal laws for educational purposes. Quoting both Mitnagdic and Hasidic sources, he aptly balances rational and mystical ideas concerning the writing of Torah scrolls and its letters. This balanced approach is reminiscent of R. Ganzfried’s magnum opus – the Kitzur Shulchan Arukh (Ungvar, 1864) in which he delineates basic Halakhot relevant to day-to-day life. The explanations R. Ganzfried gives in Keset HaSofer and the rabbinic opinions he endorses influence our contemporary understanding of Jewish scribal laws.

Surprisingly, though, both R. Ganzfried as a rabbinic scholar and, more specifically, his book Keset HaSofer have barely received attention from academia so far. It remains unclear how R. Ganzfried set out to write Keset HaSofer and in which ways he engages with both previous and contemporary discourse. As part of the interdisciplinary project “Materialized Holiness – Torah scrolls as a codicological, theological, and sociological phenomenon of Jewish scribal culture in the Diaspora”, I want to find out how R. Ganzfried engages with rabbinic literature on Jewish scribal law. A critical edition and a comparative analysis of other halakhic scribal guides will shed light on the making of Keset HaSofer and the development of these laws in the 19th century.