Annett Martini

The authors of Sefer Hasidim turned with particular diligence to what is probably the most delicate subject of scribal literature, namely, the writing of the names of God in Torah scrolls. Paramount in the Hasidic context is the high quality of the writing materials, i.e., of the inks as they concern the names of God, and also the duty of the scribes to avoid disturbing in any way with their writing habits the notion of the absolute perfection of the name. God’s name must not exhibit any holes in its immediate surroundings or even be perforated itself. In the unfortunate case of a necessary correction, “approach not where the name is, so as not to pierce the name [with the needle], but there, where the parchment is unwritten.” A particular meticulousness in the script also affects to a certain degree the words before and after the names of God:

„A sofer who has written the name of God but without rendering it readable, should again go over it with the qulmus so that the letters of the word become readable. However, if he has already begun to write the name of God and not yet completed [it], he must not suspend [work on] the letters of the name in order to mend another word.“

(SH Ms Parma 3280 H, §715)

Yet it is not only the material, but also the flow of the writing act itself that does not tolerate absences or interruptions. The Sefer Hasidim takes up the image of the scribe known from ancient scribal literature, where a king is patiently waiting to be greeted by the sofer who is himself in this moment recording the name of the heavenly king on the scroll. In such a precarious moment, the scribe must not look up when one less than him enters the writing space and addresses him.

If he is not permitted to respond to the needs of others, how much more important is it then that the scribe also represses his own needs such as the urge to spit.

„When a sofer is writing the name of God, he may not spit as long as he is not finished, but only when he has written everything.“

(SH Ms Parma 3280 H, §719)

Ultimately, the Sefer Hasidim provides the scribe with solutions in the event that a name has been inadvertently misspelled.

One exceptionally interesting writing instruction, which clearly goes beyond the scope of the rabbinic guidelines, is found in the following paragraph:

„It is written [Ex 39,30]: [And they made the plate of the holy crown of pure gold,] and wrote upon it a writing, like to the engravings of a signet, HOLINESS TO THE LORD [יהוה]. [The employed plural] and they wrote teaches that the name should be written in the presence of a greater number of people meaning ten persons. Scripture says [Lev. 22,32]: [Neither shall ye profane my holy name;] but I will be hallowed among the children of Israel: [I am the LORD who hallows you.] Thus, the rishonim, when a Sefer Torah was written, wanted the names to be written by ten righteous. There are some who say: ‘It is necessary to write [the name of God] in the presence of a quorum as a reminder that it was written for the sake of [the divine name]. For if it was not written for the sake of [the name] [the scroll] should be stored in a genizah. This holds true for every single letter.“

(SH Ms Parma 3280 H, §1762)

This passage is remarkable because its author calls for bearing witness to the ritual sanctification of God’s name in the writing of a Sefer Torah. A group of ten “righteous people” should gather in the writing space for the transcription of each name, by which the tetragram JHWH alone is probably meant, to ensure the consecration of the name. The “ten righteous” awaken associations with the story of Sodom, which could have been saved by the presence of only ten righteous souls. It is said of the righteous (zaddiq), of whom there are but few in each generation, that they maintain an impeccable way of life and an intimate relationship with God. Their presence when God’s name is written not only guarantees the holiness of this moment, in which God represented by His name enters the world, but it also refers to the grace of God, who ensures through these righteous the continued existence of the world.

We do not know to what extent this procedure was actually put into practice. In the course of our project work, however, a growing number of medieval artifacts from the Ashkenazic region has been encountered that attest to a particular performative effort in writing the names of God. Thus, one finds not only special markings of the tetragram, but also names of God obviously added later to the Torah scrolls, standing out from the rest of the text by a different ink color or by letter size and shape.

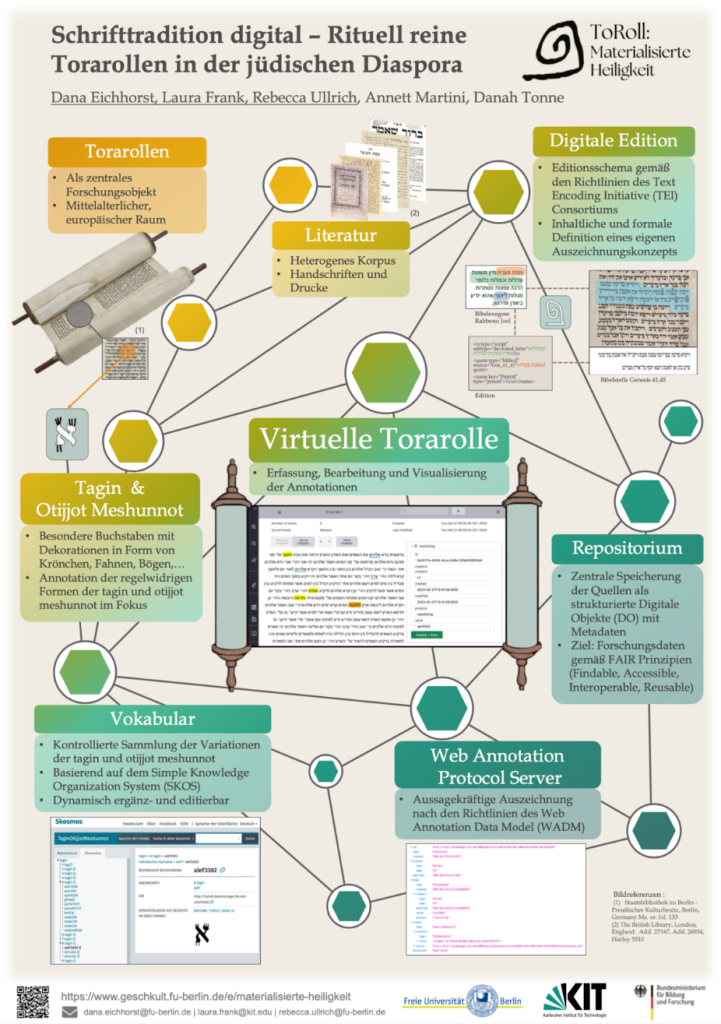

Furthermore, studies of some surviving artifacts give reason to believe that the Hasidim also maintained their own tradition of placing tagin and otiyyot meshunnot as described in the relevant treatises on the subject within Hasidic circles. These „suspected cases“ will be further investigated in the coming months and – hopefully – be presented and described in a detailed publication soon.