Katharina Hadassah Wendl

This July, our team had the chance to present our research project to the scholarly community during the 12th Congress of the European Association of Jewish Studies that took place at the Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main. Between July 16th and 20th, more than 700 Jewish Studies scholars from around the world came together to share and discuss new research findings.

Our panel, “New Perspectives on the Production and Interpretation of a Ritually Pure Torah Scroll” (Tuesday, 18th of July) attracted a diverse group of Jewish Studies researchers, scribes and material scientists. Chaired by researcher and scribe Mark Farnadi-Jerusálmi from the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, our presentations raised many fascinating questions and discussions. We presented our research interests and methods as well as preliminary findings about scribal literature from the Middle Ages until the 19th century and exegetical interpretations of Tagin and Otiyyot Meshunnot. Participants learnt about our editorial work which is being enriched by tools developed within Digital Humanities.

Starting from the Middle Ages and then moving to the 19th century, Anne May Dallendörfer commenced the panel with a presentation on the editorial considerations that went into the various manuscripts and printed editions of Barukh SheAmar, a medieval scribal guide attributed to R. Samson ben Eliezer. Next, Annett Martini delved into the mystical, multi-dimensional interpretations of letters in Sefer Alpha Beta by R. Jom Tov Lipman. Dana Eichhorst then led the attendants of our panel on an investigative tour through the manuscripts of a text called Sefer Tagin that is commonly attributed to Eleazar of Worms and showed parallels between this Sefer Tagin and R. Eleazar’s other speculative writings. Lastly, Katharina Hadassah Wendl discussed pedagogical intentions in Keset HaSofer in light of new approaches to conveying knowledge and studying Jewish tradition in the 19th century. Participants were interested in hearing more about the interpretation of scribal traditions ranging from mystical elaborations on the meanings of the letter Aleph to the increasingly stringent application of scribal laws over time.

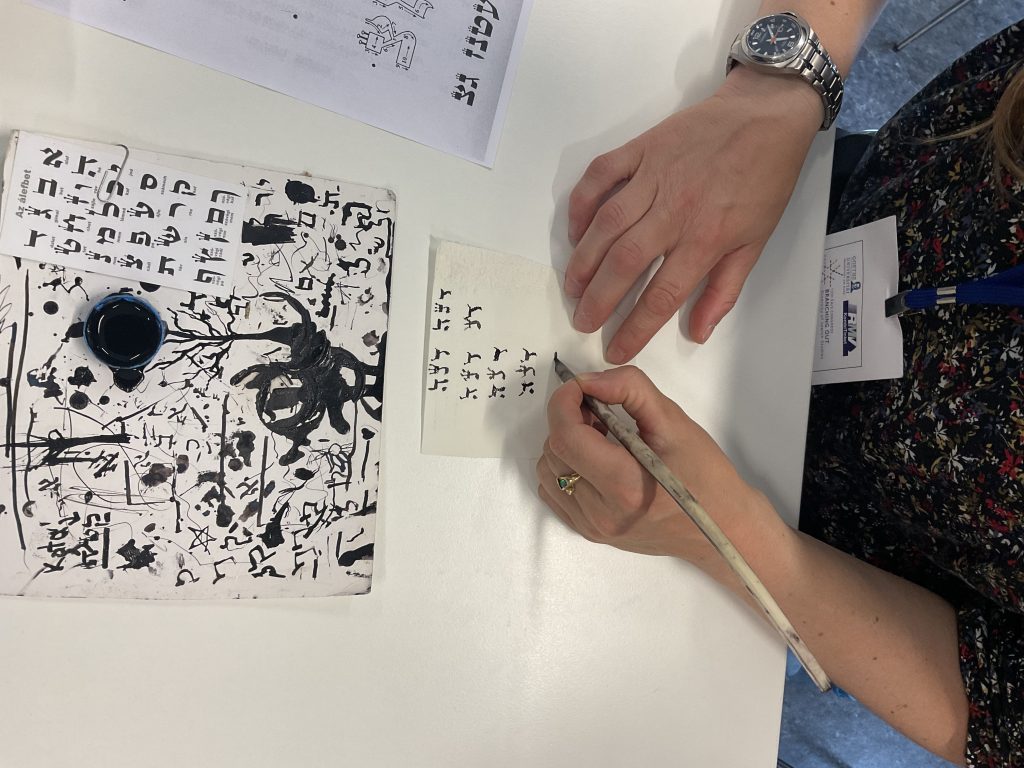

In addition to our panel on scribal literature, our colleague Zina Cohen also presented research findings about the composition of inks in medieval Torah scrolls. This research within the field of material science is also part of the interdisciplinary project “ToRoll: Materialized Holiness.” Anne May Dallendörfer and Katharina Hadassah Wendl also presented their research topics as part of the EAJS Emerge sessions for PhD candidates. Thomas Kollatz from the Academy of Sciences in Mainz, another project partner of “ToRoll: Materialized Holiness,” offered introductory and more advanced sessions on using digital research tools such as TEI and OxYgen as part of the Digital Jewish Studies Workshops. These took place in the early hours of the EAJS conference. During the sessions, Thomas Kollatz showed other researchers how our team uses Digital Humanities research tools. He was also so kind to answer our more specific queries on editing and analysing Jewish scribal literature via TEI and OxYgen. One evening, we also enjoyed participating in an impromptu workshop on how to be a scribe by our chair Mark Farnadi-Jerusálmi. Writing on klaf using feathers and ink, we made our more or less successful attempts at Safrut.

The 12th EAJS congress in Frankfurt am Main allowed us to meet former and new colleagues, discuss our research with others and learn about other projects within the field of Jewish Digital Humanities. During and in between panels, we also had fascinating conversations with researchers and scholars who we will be hosting in November for our online workshop on the Origin, History, & Interpretation of Tagin and Otiyyot Meshunnot for Writing the STaM. Looking forward to seeing you there!