Annett Martini

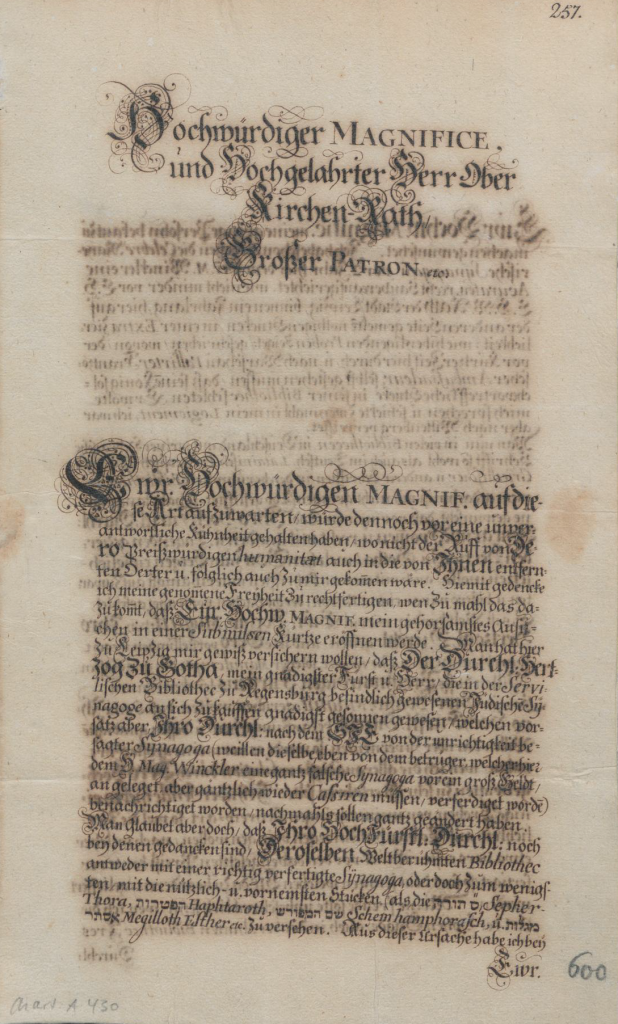

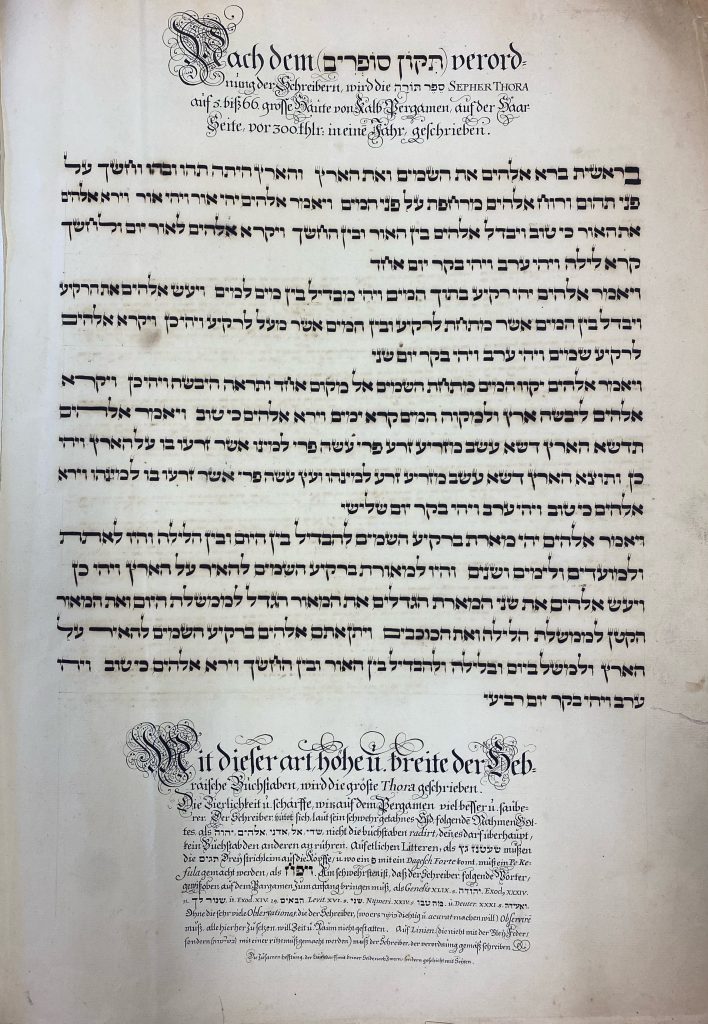

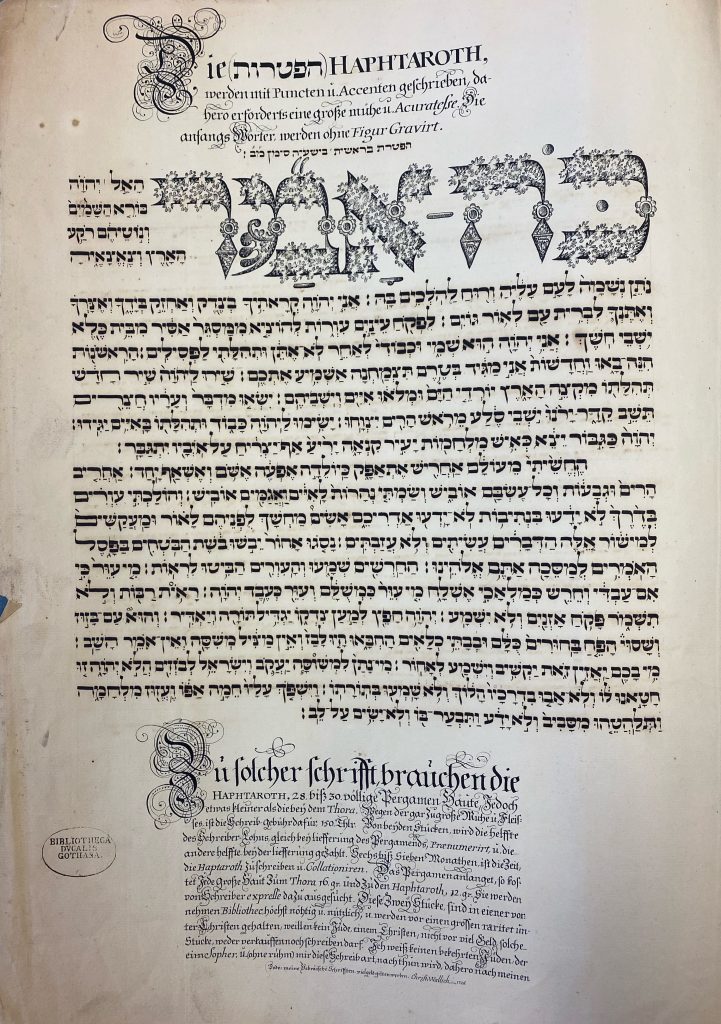

The Gotha Research Library holds a beautifully calligraphed instruction for copying Torah scrolls and haftarot. The writing instruction was recorded in 1726 by the converted Jew Christoph Wallich (1672-1743). On a large sheet of paper 50 cm high and 35 cm wide, the former professional sofer STaM and trained Hazan offers a non-Jewish readership insight into the writing of the texts to be used in the Jewish rite. Both sheets are headed with a few explanatory remarks in German, whereby most of the capital letters of the short introduction are decorated with skillfully crafted, intertwining ornamental patterns.

Sheet 1 reads:

Nach dem (תיקון סופרים) verordnung der Schreibern wird die ספר תורה Sepher Thora auf z. bis 66 grosse Häute von Kalb Pergamen auf der Haar Seite vor 300 thlr. in einem Jahr geschrieben.

[According to the (תיקון סופרים) decree of the scribes, the ספר תורה Sepher Torah is written on up to 66 large skins of calf parchment on the hair side for 300 thalers, written in a year.]

As an illustrative example, the verses Genesis 1:1-19 are cited below, as they were written by Wallich with his characteristic love for detail just beneath the lines previously drawn with a pencil. The Ashkenazic square script is decorated with fine lines running upwards or downwards at the left corners of the letter bodies; in almost all cases, the lamed features two lines extending upwards at the higher end of the neck, and occasionally the lamed also receives a slightly curved hairline at the lower end. Eventually, the seven letters shin, ayin, teth, nun, zayin, gimel and zade are adorned with three small crowns, as already recommended in the Talmud. Wallich sometimes adds an additional stroke to the shin or zade.

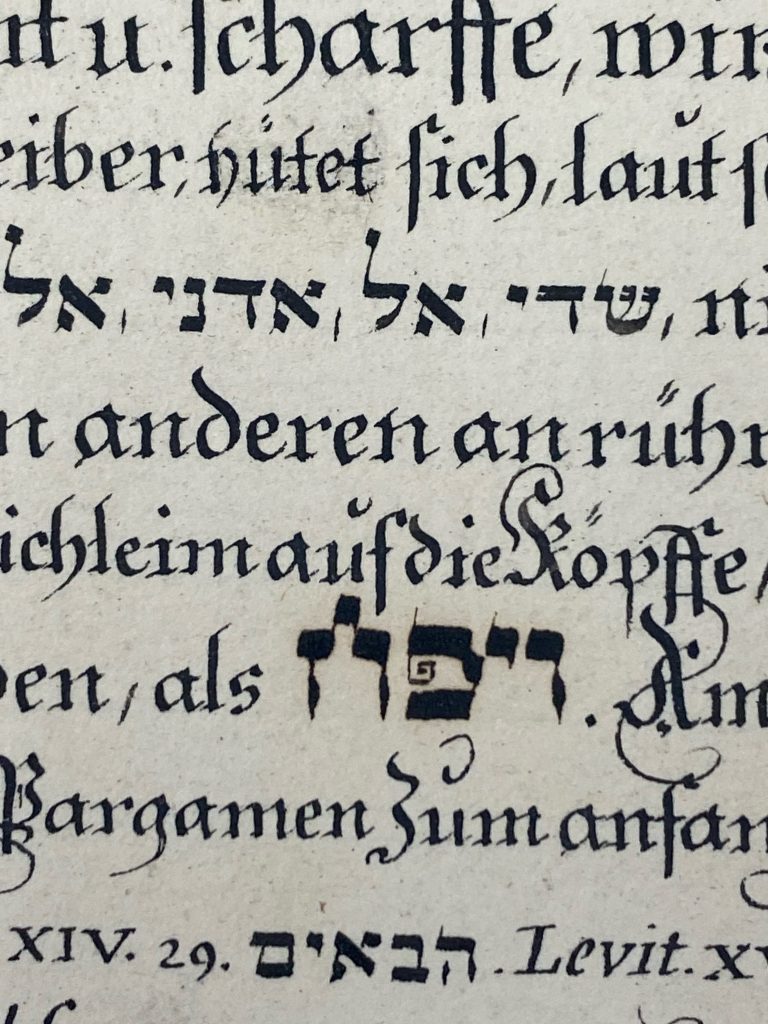

Below this impressive writing sample, Wallich provides us with some insight into several of the fundamental requirements of a ritually pure Torah scroll that the scribe ought to know:

Mit dieser art höhe u. breite der Hebräische Buchstaben wird die gröste Thora geschrieben. Die Zierlichkeit u. schärffe wird auf dem Pergamen viel besser u. sauberer. Der Schreiber hütet sich laut sein schwehr getahnes Eyd folgenden Namen Gottes als שדי,אל, אדני, אלהים, יהוה nicht die buchstaben radirt, denn es darf überhaupt kein Buchstab den anderen anrühren. Auf etlichen Litteren als שעטנז גץ müßen die תגים Drei strichleim auf die Köpffe, u. wo ein פ mit ein Dagesch Forte komt, muß ein Pe Kefula gemacht werden als ויפח. Am schwehrsten ist, daß der Schreiber folgende Wörter gewiß oben auf dem Pergamen Zum anfang bringen muß als Genesis XLIX.8 יהודה, Exodus XXXIV.11 שמר לך, it. Exod. XIV.29 הבאים, Levit. XVI.8 שני, Numeri. XXIV.5 מה טבו u. Deuter. XXXI.8.[sic.]ואעידה. Ohne die sehr viele Observationes, die der Schreiber (wo ers כושר dichtig u. acurat machen will) Observiren muß, alle hierher zu setzen, will Zeit und Raum nicht gestatten. Auf Linien (die nicht mit der Bley Feder, sondern (בשיטות) mit einer ritze muß gemacht werden) muß der Schreiber der verordnung gemäß schreiben. Die Zusammenhefftung der Häute darf mit keiner Seide noch Zwern sondern geschieht mit Seyten.

[With this kind of height and width of the Hebrew letters the largest Torah is written. The delicacy and sharpness is much better and cleaner on the parchment. The scribe is careful not to erase the following names of God as שדי, אל, אדני, אלהים, יהוה, according to his own oath, because no letter may touch another. On some letters, such as שעטנז גץ, the tagin must be made of three strokes on the letter heads, and where a פ comes with a Dagesch Forte, a Pe Kefula must be made such as is the case with ויפח. The most difficult thing is that the scribe must certainly put the following words at the top of the parchment, at the beginning [of the column], as Genesis XLIX.8 יהודה, Exodus XXXIV.11 שמר לך it. Exod. XIV.29 הבאים, Levit. XVI.8 שני, Numbers. XXIV.5 מה טבו u. Deuter. XXXI.[2]8. ואעידה. Without the many observations which the scribe (where he wants to make them dense and accurate) has to observe, time and space will not permit to place them all here, [the scroll is] not kosher. The scribe should write on lines (which must not be made with a plumb quill, but (בשיטות) should be scrached) according to the regulations.The sewing together of the skins must not be done with silk or twine but with strings made of sinew]

Wallich summarizes for a layperson the most important requirements for a ritually pure Torah scroll: the obligatory parchment, the line drawing, and the sewing of the leaves with sinew are all mentioned, as are the tagin, the repairing of the names of God, and the scribal tradition. The latter is referred to with the acronym ביה שמו- bejah šemo, suggesting that six columns of a Torah scroll should begin with a specific word. Here Wallich refers to the Ashkenazi tradition, according to which the beit stands for berešit (Gen 1:1), the he for habba’im (Ex 14:28), and the vav for the word wea’idah (Deut 31:28). The yud refers to the first letter of the word yehudah (Gen 49:8), the šin to the first letter of the word šemor (Ex 34:11), and the mem stands for mah tobu (Num 24:5).

These explanations do not probe the depths of the Jewish writing practice, but rather are intended to give an impression of the expert knowledge that is required for this demanding work.

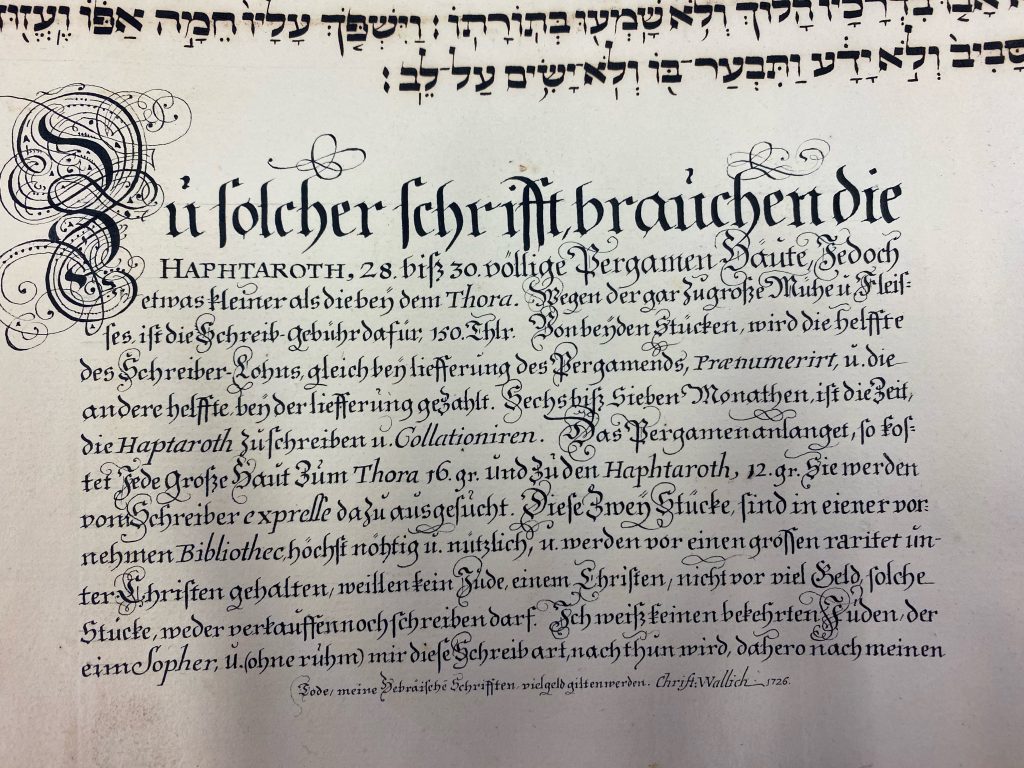

Wallich proceeds in a similar way on the second sheet, where the copying of the haftarot is described, likewise accompanied with a writing sample. This is remarkable since rabbinic literature as well as scribal manuals are primarily concerned with the writing of the STaM and – if at all – with the copying of the megillot.

Wallich first notes:

Die (הפטרות) HAPHTAROTH werden mit Puncten u. Accenten geschrieben dahero erforderts eine große mühe und Acuratesse. Die anfangs Wörter werden ohne Figur Gravirt.

[The (הפטרות) haftarot are written with punctuation and accents, so it requires great effort and accuracy. The initial words are engraved without figures.]

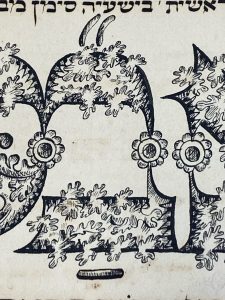

This brief remark is followed by another writing example, drawn from the Haftarah Yeshayahu to the Parashah Genesis 1:1-6:8, which corresponds to the prophetic passage Isaiah 42:5-25. Wallich manages to transmit the passage with just a few embellishments to the letters in the form of fine hairlines, for example, on the lamed or the pe. Yet, the first words of the haftarah – כֹּה-אָמַ֞ר – are enlarged and decorated with floral ornaments that are entwined with the first letters.

Wallich explains below the artistically written prophet section:

Zu solcher schrifft brauchen die HAPHTAROTH 28 biß 30 völlige Pergamen Häute, Jedoch etwas kleiner als die bey dem Thora. Wegen der gar zugroße Mühe u. Fleisses ist die Schreib-gebühr dafür 150 Thlr. Von beyden Stücken wird die helffte des Schreiber-Lohns gleich bey liefferung des Pergamends Praenumeriert u. die andere helffte bey der liefferung gezahlt. Sechs bis sieben Monathen ist die Zeit die Haptaroth zu schreiben u. Collationiren. Das Pergamen anlanget so kostet Jede große Haut Zum Thora 16 gr. Und zu den Haphtaroth 12 gr. Sie werden vom Schreiber expresse dazu ausgesucht. Diese zwei Stücke sind in eiener vornehmen Bibliothec höchst nöthig u. nützlich u. werden vor einen grossen raritet unter Christen gehalten, weillen kein Jude einem Chriften nicht vor viel Geld solche Stücke weder verkauffen noch schreiben darf. Ich weiß keinen bekehrten Juden, der eim Sopher u. (ohne ruhm) mir diese Schreibart nachthun wird, dathero nach meinem Tode meine Hebräischen Schrifften viel geld gilten werden. Christ. Wallich 1726.

[With this script [size], the haftaroth require 28 to 30 complete parchment skins, but somewhat smaller than those of the Torah. Because of the great effort and diligence involved, the scribe’s fee is 150 Thalers. Half of the scribe’s fee is paid when the parchment is delivered, and the other half is paid when [the project] is completed. Six to seven months is the time [needed] to write the haftarot. The parchment costs 16 groschen for each large skin for the Torah, and 12 groschen for the haftarot. The skins are selected in advance by the scribe.

These two pieces are highly necessary and useful in a noble library and are considered a great rarity among Christians because a Jew may neither sell nor write such pieces for a Christian, not even for much money. I know of no converted Jew who is a sofer and (and without praising myself) can hold a candle to me in this art of writing, thus after my death, my Hebrew writings will be valued at much money. Christ. Wallich 1726.]

Finally, the question remains as to who Wallich wrote these sample pages and the corresponding explanations? These two representative sheets actually evoke the impression that Wallich was advertising his skills in the art of Jewish writing in order to impress Christian customers. Apparently, converted Jews like Wallich still benefited from the interest in the Jewish tradition shown by Christian scholars, an interest which had already emerged at the beginning of the 16th century. The Enlightenment also saw a growing interest in the customs and rituals of Jewish teaching. This was approached with historical source criticism and an emphatically rational perspective – often fueled by pronounced anti-Semitism.

In fact, another document held in the Gotha Research Library allows us to understand the intended purpose of these remarkable sheets. A letter written by Wallich on 29 August 1726 in Leipzig to Ernst Salomon Cyprian, a Gotha church councillor and vice-president of the High Consistory, reveals that Wallich had already written various manuscripts for the ‘Meyersche Judenschule’ a few years earlier. The ‘Meyersche Judenschule’ was a project initiated by Johann Friedrich Mayer (1650–1712) at the University of Greifswald. As part of it, Jewish ritual objects were installed in the synagogue as an educational exhibition for students. Wallich, who had been registered at the University of Greifswald since 1706, was actively involved in this project. He equipped this educational synagogue with ritual objects and also contributed the corresponding explanations. Once this educational synagogue had later become part of the university library’s collection, Wallich enriched the exhibition in 1724, now called “Mayer’s Judenschule,” with a selection of ritually relevant writings from the Jewish tradition.

The abovementioned letter to Cyprian not only reveals which writings Wallich’s copied for the synagogue. We also learn from this letter what the sample sheets discussed above were all about:

[S. 1] … Man glaubet aber doch, daß Ihro Hoch Fürstl. Durchl. noch bei denen gedancken sind, Deroselben Weltberühmten Bibliothec antweder mit einer richtig verfertigte Synagoga oder doch zum wenigsten mit die nützlich u. vornemsten Stücken (als die ס״ תורה Sepher Thora, הפטרות Haphtaroth, שם המפורש Schem hamphorasch u. מגלות אסתר Megilloth Esther etc.) zu versehen. Aus dieser Ursache habe ich bey [S. 2] Ewr Hochw. Magific. meine gringe Persohn bekannt zu machen gewünschet. Ich habe schon ehedeßen dieselebre Mayerische Synagoge u. vor 2 Jahr dem […] Rath der Stadt Leipzig binnen ein Jahrlang hier auf der anderen Seite gemelten nöthigen Stücken in einer Extra Zierlichkeit – wie hibeyligenden Proben zeiget – geschrieben, wovon der vor kurtzer Zeit hier durch u. nach Warschau Passirter Frantzöscher Ambassadeur selbst gestehen müssen, daß seinem König solche vortreffliche Stücke in seiner Bibliothec fehleten.

[(p. 1) It is believed, however, that Your Most Serene Highnesses are still thinking of providing this world-famous library either with a properly prepared synagogue or at least with the most useful and most important pieces (as the ס״ תורה Sepher Torah, הפטרות haftarot, שם המפורש Shem Hamephorasch and מגלות אסתר Megillot Esther etc.). For this reason I have wished to make my low person known to [p. 2] Your Reverend Magnificant. I have already built the ‘Mayer’s Synagogue’ and two years ago, within a year, I produced the abovementioned necessary pieces for the […] Leipzig City Council with a particular delicacy – as the enclosed samples show – of which the French ambassador, who recently passed through here and in Warsaw, himself had to confess that his king lacked such excellent pieces in his library.]

It appears that Wallich extended to Cyprian an offer to both set up a synagogue for the library of the sovereign of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, designated for teaching purposes in the style of the ‘Mayerian Synagogue,’ and to provide it with appropriate ritual texts. Wallich enclosed samples of the Sefer Torah and the haftarot with his letter so as to convince Cyprian and – through him – the sovereign of his expertise in the art of Jewish writing. Wallich also added a few details about his career to this “letter of application,” which should not be withheld here:

[3] Meine gringe Person anlanget bin ich in Worms von reichen Jüdischen Eltern gebohren u. habe unter dem (unter den Juden gewesenen berühmten (רב Rabh) Rabbi Ahron Darschon das Rabbnische Studirt. Und weillen ich lust zu Schreiberey hatte, hat mein (gottgebe Seelig) verstorbenen Vatter das Sophroth (סופרות) Schreibkunst mich verlernert lassen u. bin ein Examinirter berühmter (סופר) Schreiber geworden, auch viermahl das Thora, eben so viel Haphtaroth u. viele Mesusoth, Kameoth, Tephillin u. ein Scheide Brieff unten Juden gantz Koscher geschrieben. (Leipzig, 29. August 1726)

[(3) As for my minor person: I was born in Worms of rich Jewish parents and studied rabbinics under the famous (רב Rabh) Rabbi Ahron Darschon. And because I had a desire to write, my deceased father (God rest his soul) taught me the art of writing and I became an examinated famous (סופר) scribe, also writing the Torah four times, as many haftarot and many mezuzot, Kameoth, tefillin, and a get, which is kosher among Jews.

(Leipzig, 29 August 1726)]

The two rather coincidental finds from our project week in Gotha lead deep into Jewish-German relations at the beginning of the 18th century and certainly merit closer examination.