Dana Eichhorst

In medieval Europe, demons, shapeshifting and vampire-like creatures were part of both Christian and Jewish imaginary worlds and found their way into many legends and tales. An invaluable historical source for medieval Ashkenaz is the Sefer Hasidim from the circle of the Haside Ashkenaz.

In this Hebrew book we read not only about demons, ghosts, and marvellous creatures but also about so-called shapeshifters. In one passage of the Sefer Hasidim, three different types of creatures are mentioned: Werewolves, Strigae and Mares.[1] However, neither werewolf nor Mare are at the centre of the story, but so-called Strigae.[2] This is the specific name given to women who are said to be able to change their shape. The description most frequently found in the Ashkenazi sources is that they morph into a cat, but there are also descriptions in which they are described as blood-drinking creatures reminiscent of vampires. Sefer Hasidim contains an exemplary passage in which the fate of such a woman is vividly described. This short text can undoubtedly be described as narrative, but the sentence that introduces the story is also significant, as it says that Striga, Mare, and werewolf, who can change their shape, were created in the twilight.[3]

The motif of monsters and demons, werewolves, fairies, and other wondrous creatures in medieval sources, both Jewish and Christian, could not simply be rationalized away in the research of the nineteenth and following centuries. So, such ideas were usually plainly and simplistically declared to be superstition. And the origin of those Ashkenazi superstitious delusions that emerged in the 12th and 13th centuries were traced back to the Christian belief in devils and witches as they could not be genuinely Jewish.[4]

The various ways in which fabulous creatures are contextualized and perceived, as revealed in the medieval Hebrew sources themselves, are only starting to find a resonance in research. There is now a growing awareness that marvellous monsters and demons in medieval Ashkenaz were not only the subject of eerie stories, but also of theological considerations.[5]

In the Sefer Tagin, attributed to the authorship of Eleazar of Worms, we find a significant passage that can be related to the one in Sefer Hasidim. However, werewolves and Strigae are not protagonists of a narration in the Sefer Tagin.

Unlike the work of the same name, this Sefer Tagin by Eleazar is not a scribal manual. But it is also not a systematic treatise on the tagin. In simplified terms, the text can rather be described as a kind of speculative-esoteric exegesis on various aspects of Ma’aseh Bereshit and Ma’aseh Merkavah in which the tagin play a special role. This is also the case in said passage of the treatise, which deals with a special interpretation of Genesis 2:2[6] and the adornment of the third letter of the verse’s first word waikhal with tagin.

With reference to Pirqe de Rabbi Eliezer 19:1[7], the author concludes that God did not complete his work in its entirety on the seventh day. For there was one thing in his work that had not yet been completed, namely demons. In their incorporeality, demons resemble women who turn into cats and kill children, for example, or men who turn into wolves and devour people. The former are called Strigae (שטרייא), the latter werewolves (וַורְווֹלְף). Just like demons, those humans who shape-shift into wolves, cats, or other creatures were not actually created, but were brought forth in the twilight.

Mares (מריאים) are also mentioned in this context, but according to the author they differ from demons in that they have a body and a soul. As in Sefer Hasidim, Striga, werewolf and Mare are also mentioned in Sefer Tagin, and it is explicitly said of Striga and werewolf that they were created in the twilight – just like demons.[8] However, the passage differs significantly from that in Sefer Hasidim. In the context of an exegesis of Genesis 2:2, the author of the Sefer Tagin takes up the rabbinic exegetical tradition about the ten things that are said to have been created on the evening of the Sabbath at twilight. He follows the idea that demons also belong to this group, to which he adds the group of shapeshifters mentioned above.

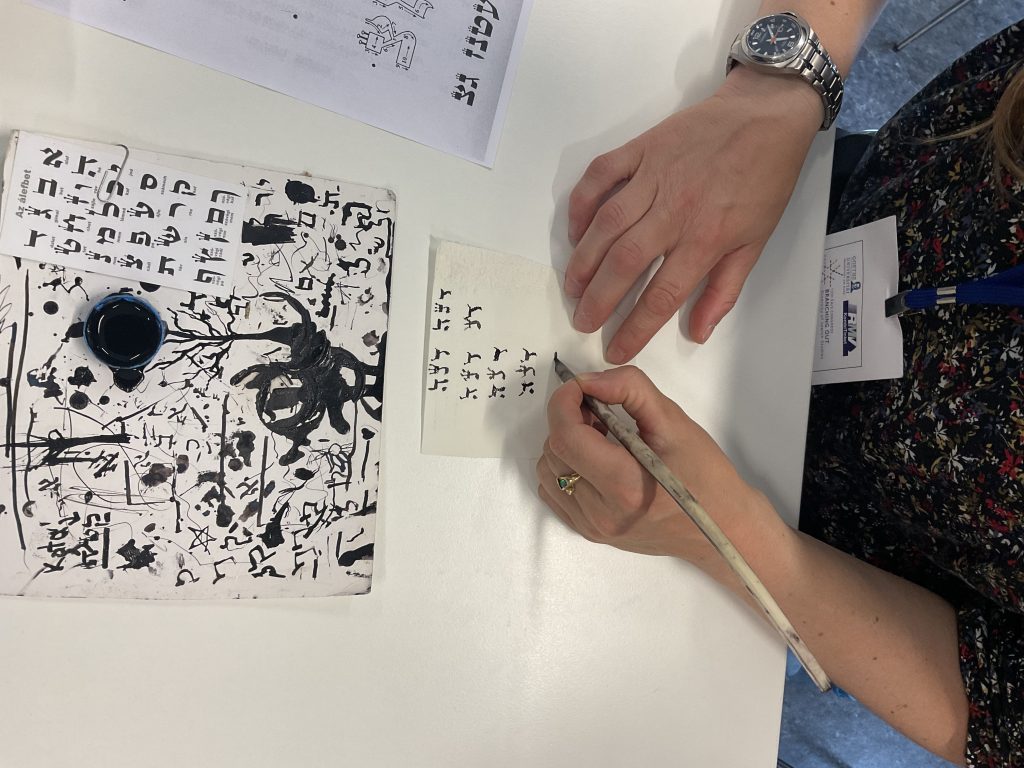

A key part of this specific reading of the Bible verse is the interpretation of the letters and the tagin. But what role do the tagin actually play here? In some, but not all, surviving versions of the scribal manual Sefer Tagin, it is instructed that the letter kaph in the word waikhal is to be embellished with two tagin. Eleazar’s remarks can therefore be understood as an attempt to explain the scribal instruction, whereby, according to him, the tagin are just as important as the letters for an understanding of the Holy Scriptures. This is evident from the context of said passage, as the exegesis of Genesis 2:2 is preceded by an interpretation of Isaiah 44:7[9]. In it, we read, among other things, that the letters and the tagin foretell what will be in the future and that anyone who renders a righteous decision in truth will be called Elohim – as if he were a partner in the act of creation.[10] With regard to the interpretation of the biblical passage from Isaiah, the author also explains the meaning of the tagin in the word Elohim. According to him, the three tagin on the letter he refer to the fact that man cannot see demons (shedim), demons in turn cannot see angels, and the angels cannot see the Holy One, blessed be He.[11]

Like the mouth of the earth, the manna in the desert, the shape of the alphabet, etc., demons, werewolves and Strigae do not exist before a certain point in time, which is determined for them by God’s decree, and therefore they too are deemed by the author to be creatures of the twilight.

In view of Eleazar’s account, I am inclined to argue that holding demons, werewolves and Strigae to be true is not simply the result of superstition, but that they are understood as part of divine creation and the cosmic order. The notion that demons are just as much a part of a divine order is also found in Eleazar’s main speculative work Sode Razayya, where it says at one point that God will judge[12] four times: over angels, humans, demons (shedim), and all living beings.[13]

In the Sefer Tagin, Striga and werewolf are part of an original exegesis of the Genesis verse, which the author links to the tagin tradition with which he was familiar. In doing so, he links the interpretation of one verse with that of another, while also taking the tagin into account. The text passage not only sheds light on Eleazar’s understanding of the tagin in the respective Bible verses, but also on medieval understandings of such wondrous beings that may seem incomprehensible to us today, but which at the time were the subject of legitimate considerations inter alia about corporeality, the soul, and the workings and becoming in the divine order of creation.

[1] Cf. MS Parma H 3280, § 1465 and Bologna printed edition of 1538, § 464.

[2] Cf. also MS Parma H 3280, §§ 1466-1467 and Bologna printed edition of 1538, §§ 465-467. In general, see Daniel Ogden, The Strix-Witch (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2021).

[3] MS Parma H 3280, § 1465: יש נשים שקורין להם {שטר} שטירייש^ אותן מַרְש וולְף אותן נבראו בין השמשות שיעשו דבר {וישתת} וישתנו בברייתן. Quoted from the Princeton University Sefer Hasidim Database: https://etc.princeton.edu/sefer_hasidim/index.php.

[4] See, for instance, Moritz Güdemann, Geschichte des Erziehungswesens und der Cultur der abendländischen Juden während des Mittelalters und der neueren Zeit, vol 1: Von der Begründung der jüdischen Wissenschaft in diesen Ländern bis zur Vertreibung der Juden aus Frankreich (X.-XIV. Jahrhundert), (Wien: A. Hölder, 1880), esp. p. 217.

[5] See, especially, David I. Shyovitz, ‘Christian and Jews in the Twelfth-Century Werewolf Renaissance’, in: Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 75, no. 4 (Oct. 2014), pp. 521-543. On demons in the medieval Hebrew narrative, see especially the research of Dudu Rotman.

[6] “And on the seventh day God ended his work which he had made; and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had made.”; ויכל אלהים ביום השביעי מלאכתו אשר עשה וישבת ביום השביעי מכל־מלאכתו אשר עשה.

[7] According to the editio princeps, 1544: “Ten things were created (on the eve of the Sabbath) in the twilight (namely): the mouth of the earth; the mouth of the well; the mouth of the ass; the rainbow; the Manna; the Shamir; the shape of the alphabet; the writing and the tables (of the law); and the ram of Abraham. (Some sages say: the destroying spirits also, and the sepulchre of Moses, and the ram of Isaac; and other sages say: the tongs also.).”

[8] Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Opp. 540, fol. 254r: כאשה שנהפכת למה שהיא חפצה כגון לחתולה ממיתה ילדים ואע”פ ופעמים לגדולים ונקראת שטרייא וכן האיש שנהפוך לזאב ואוכל בני אדם אילו מזיקין נבראו בערב שבת בין השמשות וזהו שקורין וַורְווֹלְף שבני אדם משתנין לחיה לזאב ולחתול ולא נבראו ממש אלא נגזר בין השמשות שיהא כך ולא היה קודם לכן כך כגון פי הארץ לא היה פה שם אלא שנגזר וכן פי הבאר לפי שעה כשנתפללו הגר וישמעאל כך בפרקי ר‘ אליעזר.

[9] “Who is like me? Who will call, and will declare it, and set it in order for me, since I established the ancient people? Let them declare the things that are coming, and that will happen”; ומי־כמוני יקרא ויגידה ויערכה לי משומי עם־עולם ואתיות ואשר תבאנה יגידו למו. In a piyyut commentary from medieval Ashkenaz we find an interesting parallel, see the edition of a commentary contained in MS Parma 6555, published by Elisabeth Hollender, Piyyut Commentary in Medieval Ashkenaz, p. 75*: להעמית: אם יסגלו מצות ומעשים טובים יהיו עמיתי כמוני. מי רוצה להיות כמוני. יקרא קריאה ויגידיה אגדה ויערכיה סדרים. מי שומי עם עולם. בעבור זה העולם עומד. ואותיות מי שהוא יודע לצרף האותיות אשר תבואנה שעתיד הקב”ה לגלות לו סוד.

[10] This passage is similar to another passage in Eleazar’s Sefer Tagin that deals with sorcery and magic, MS Opp. 540, fol. 240r: “God made the tagin as well as all of those who acknowledge and appreciate His creation His partners.” (וכל מי שמוציא דין לאמיתו לאור כאילו היה שותף עמו במעשה בראשית ועל כן עשה תגין עליהם כאילו הם עמו שותפין).

[11] See a similar passage in Eleazar of Worms’s Sode Razayya: The demons (shedim) do not know where the angels dwell, while the angels and seraphim do not know where the shekhina and the kavod reside, and with regard to humankind we are told continually that the secrets of the Godhead and the divine name have only been revealed to the righteous and the God-fearing. Cf. BL, MS Add 27199, fols 279v-280r.

[12] Cf. Mishna Rosh ha-Shana 1:2.

[13] Cf. BL, MS Add 27199, fol. 362v.