Anne May Dallendörfer

Scribes can generally be considered artists and craftsmen. In contexts like the Jewish one, they are first and foremost preservers of holy texts and keepers of tradition. They are thus assigned a social role of great importance and their work is subject to strict rules with regards to form and ritual purity. At times, while preserving a fixed text and the tradition which depends on it, the scribe simultaneously gains access to a knowledge that is otherwise hidden from the other community members. He thus acts as a keeper of the community’s tradition at large but also as a guardian of a secret knowledge kept and preserved by only a few.

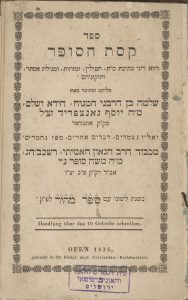

We find one such portrayal of the scribe in the 13th century Jewish scribal manual “Barukh she-amar” which has been attributed to the scribe R. Samson ben Eliezer.[1] In this manual, R. Samson sets out to rectify many of his fellow scribes’ mistakes and negligence concerning the writing of STaM (Sefer tora, Tefillin and Mezuzot). He thereby deals extensively with the manufacture of kosher parchment and the rules for writing. One aspect of these rules is the correct form of the Hebrew letters. It is here that the author discloses that he is in possession of some hidden knowledge, as he reveals the metaphysical meaning behind the letter shapes. Concerning this latter part, however, he seems hesitant to reveal too much as these are the secret aspects of his scribal knowledge. He even calls himself a “gossip” fearing he might disclose too much. Here is an excerpt from his writing:

And here I am, “A gossip goes about telling secrets” (Proverbs 11:13) with a little allusion for those who understand in accordance with my limited understanding. Although in my sins I am not worthy to allude to these great secrets which even hinting at [the fact] that I have a little knowledge [of them] is forbidden to me.

Perhaps the prohibition to share these “great secrets” hidden in the letter shapes is just a rhetorical device to give more weight and a sense of importance to his ensuing words. Nonetheless, throughout Rabbi Samson’s writing, one senses an underlying fear that this knowledge might fall into the wrong hands, much of which “was not given to be written.”

Though he finds himself unworthy to share these great secrets, he nonetheless does so, albeit in a quite enigmatic way:

For the dalet points out that the ‘ayin is kneset Israel and the oral Tora, the bride mentioned in Song of Songs, and she is Bakol the daughter of Abraham our father, and she is the kingdom of the house of David, and this dalet which is in eḥad is a thick one. And the vav which is on top of [the dalet] hints that the tav is the six ends [of the world] and a looking glass, it is the bundle of life, the tree of life, and the written Tora, and the two tagin which are on the vav hint at Bina and Ḥokhma the supreme, preceding and splendid, until Ein Sof.

Whatever these symbols hidden in the shape of the letters dalet and vav might mean, R. Samson ends with the comment:

And our rabbis, blessed be their memory, and the learned will understand. And the Lord, may He be blessed, revealed to me wonders from His Tora because of His great name.

It seems clear that Rabbi Samson believed that in his profession as a scribe he had witnessed “wonders” from the Tora through which he had received knowledge of the great secrets of God. In their form and shape, the Hebrew letters allude to symbols whose meaning is not self-explanatory at first sight. It is down to the scribe to learn, preserve and pass on this knowledge – to those who understand. Besides continuing the textual tradition, in learning the correct shape of the Hebrew letters the scribe acts as a preserver of a secret knowledge about God which is otherwise hidden from the uninitiated.

[1] It has been subject to debate whether R. Samson really was the author or whether certain excerpts can be attributed to others. The themes explored in the passage mentioned here have also been connected with his student Yom Tov Lipmann.