22. August 2022, by Christian Casey

The Zodiac Glossary website is now available online at zodiac.fly.dev

A Glossary of Zodiacal Terms

As one component of the broader aims of the Zodiac Project, we’re creating a glossary of zodiacal terms from the ancient Mediterranean and near East.

The usefulness of such a project for our research is easy enough to see from a few examples. Say that you wanted to know about the Egyptian conceptualization of Aries. You could look up the English word in the glossary (“Aries”), find a few matching examples, and see that this concept is realized in Egyptian as: 𓇋𓋴𓏪𓄛𓏤 ỉsw “ram” and: 𓁶𓏤 dpỉ “first” (as in the example from Andreas Winkler’s recent blog post “A New Look at an Old Horoscope”). 𓇋𓋴𓏪𓄛𓏤 ỉsw “ram” is easy enough to understand, but what about 𓁶𓏤 dpỉ “first”? One likely explanation is that the Egyptian zodiac was ordered like the Babylonian one, with Aries as the first element and the others following after. This sort of observation immediately suggests a cultural connection between the two, which is exactly what we are here to explore.

Or you might wonder about the connections between the gods and the planets. For instance, the god Jupiter is associated with Greek Zeus and Egyptian Amun, but the planet Jupiter is known by a variety of Egyptian names: “Horus the merchant”, “Horus the secret one”, “Horus the magician”, none of which have anything to do with Jupiter or Zeus or even Amun. Looking at such evidence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the Egyptian planet names predate any direct connection with neighboring cultures and were borrowed into the zodiacal system from local traditions. Here we have the opposite of the previous example: a telling lack of similarity where we might expect to find one. This sort of detail helps nuance our understanding of the spread of the zodiac between various cultural groups.

Even with such simple examples (where the explanations are already known in advance), it’s clear enough that having such a glossary simplifies the task of doing research. Looking at texts one at a time demands a strong memory for seemingly minor details, such as the spelling of a single word, while extracting these details and putting them together into one view makes the connections much more obvious. It also allows us to detect relationships between ancient languages, even in cases where no single member of the team knows all the languages involved.

All Beginnings are Difficult

We can talk endlessly about constructing such a glossary, but until we actually start doing it there’s no way to know how it’s actually going to work. At some point, we have to stop talking and start building, then adjust our strategy as we go along. That’s why we now have a prototype version, currently in alpha testing.

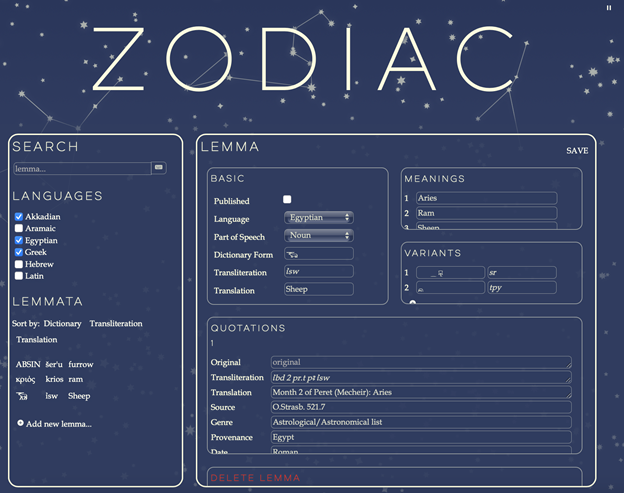

[The Zodiac Glossary working prototype as of July 20, 2022.]

The final version will probably be different in many ways, but you can already see most of the parts that we wanted to include from the beginning.

On the left, there’s a way to search for existing lemmas, a way to filter by languages, a way to sort the results, and an option to add a new lemma (only available to registered users in the final version).

On the right side, in the Lemma panel, there’s the usual information you would expect in any ancient language glossary, plus lists of variants and quotations to help us with our research. Finding an interesting pattern or cross-cultural connection is not the end of the story. We also have to refer back to the original text to dig in further. Or, at the very least, we need to cite our sources. Finally, there is a way to delete the lemma, which will also only be available to registered users in the future.

One important feature, which is not pictured here because I haven’t implemented it yet, is a way to link different lemmas together. For instance, it would be useful to link the Greek lemma κριός krios with the Egyptian 𓇋𓋴𓏪𓄛𓏤 ỉsw because both refer to the sign Aries. Having those links between ancient languages will allow us to explore connections in a lateral traversal through the networks of relationships within languages. This is one of the most important aspects of collaborative work like this involving specialists in different fields: we can find things that no single one of us is equipped to discover alone.

The Glossary will also be available to anyone who wants to use it via this same public-facing website. However, editing features will only be available to registered users. The long-term destiny of this part of the project is still an open question. Perhaps others will take it over and build on it after us (in which case we will allow other collaborators to register as editors) or perhaps it will simply remain online as a valuable tool for anyone who wants to use it. The one outcome that we are designing against from the beginning is one that is all too familiar with grant-funded academic projects: disappearing into the ether.

Surviving the Academic Grant Cycle

Zodiac is funded by a five-year ERC grant. Like all such projects, its trajectory is predicated on the assumption that deliverables come in the form of traditional academic publications: books, journal articles, etc. But books are very different from databases. For one thing, the cost of producing and preserving a physical book is paid by the reader (in one way or another), while the cost of serving up a website is paid by the creator. At the same time, books can remain on library shelves indefinitely. By the time a library book decays from age, the information in it will have been replicated elsewhere or superseded entirely. But websites don’t simply sit on shelves. They must be maintained and paid for on a continuous basis.

The success of this project in the long term requires a solution to this problem: a website that remains functional at very low cost forever. There are already ways of creating free websites with static content (content that is prepared in advance and doesn’t change), but there is no easy way to build a free website for dynamic content (content generated on the fly, such as a webpage that includes information pulled from a database). The Zodiac Glossary is thoroughly dynamic, so we need to find an affordable way to build the site that allows it to become free (or very nearly free) after the term of the grant ends.

Our current working approach is to use a variety of tools on the Amazon Web Services platform in an arrangement that keeps costs as low as possible. There is an inevitable tradeoff here. While it may be possible to keep costs down using AWS “Free Tier” services, this limits the number of visitors that the website can serve. Such an approach may prove ideal for smaller academic projects, where daily visitor numbers are expected to remain low, but it may not work in all circumstances.

Depending on the nature and scope of a project, different solutions may be creatively combined to maximize benefit and minimize cost. I’m currently working on several simultaneous approaches to the academic website funding problem (some developed as part of my work with Zodiac, some from my previous position as the CLIR postdoc at ISAW). If you’re interested in learning what I’ve discovered or discussing other solutions, consider attending my paper at this year’s ASOR conference in Boston (November 16–19), “Star Seeds: Building a digital glossary for the Zodiac Project that will outlive the project’s funding” in the Digital Archaeology and History section.

Coming soon…

Though the Zodiac Glossary is still in development, we expect to have a working, publicly-available version of the website online within the next few months. Check back for more updates, and feel free to contact me with questions or ideas: christian.casey@fu-berlin.de.