June 17, 2024, by Solmeng-Jonas Hirschi

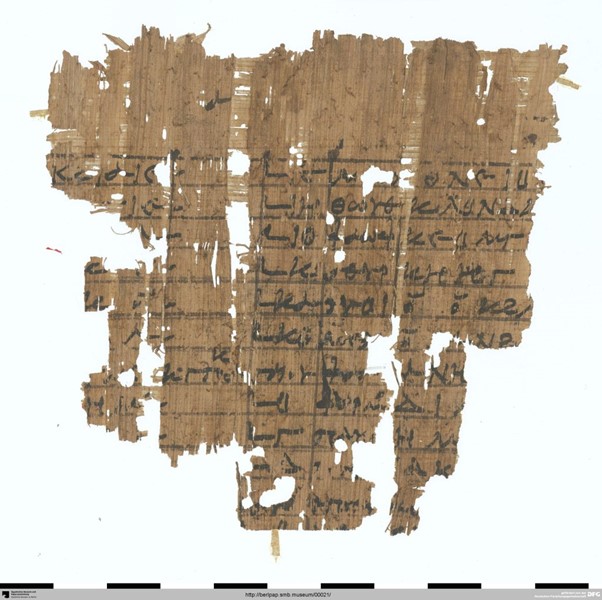

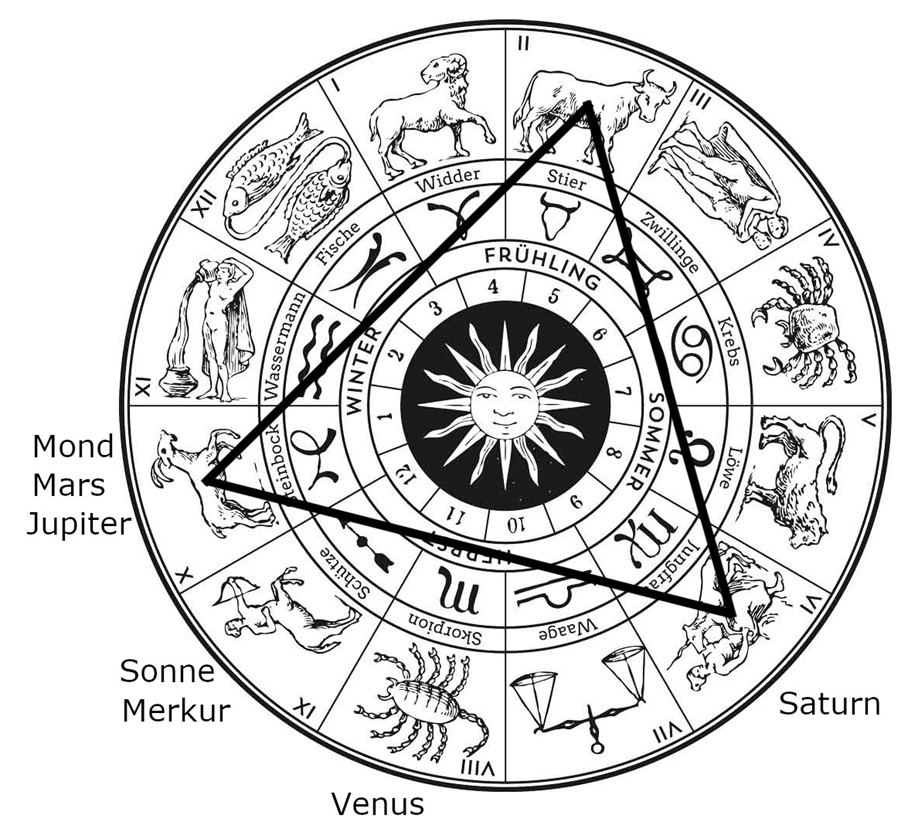

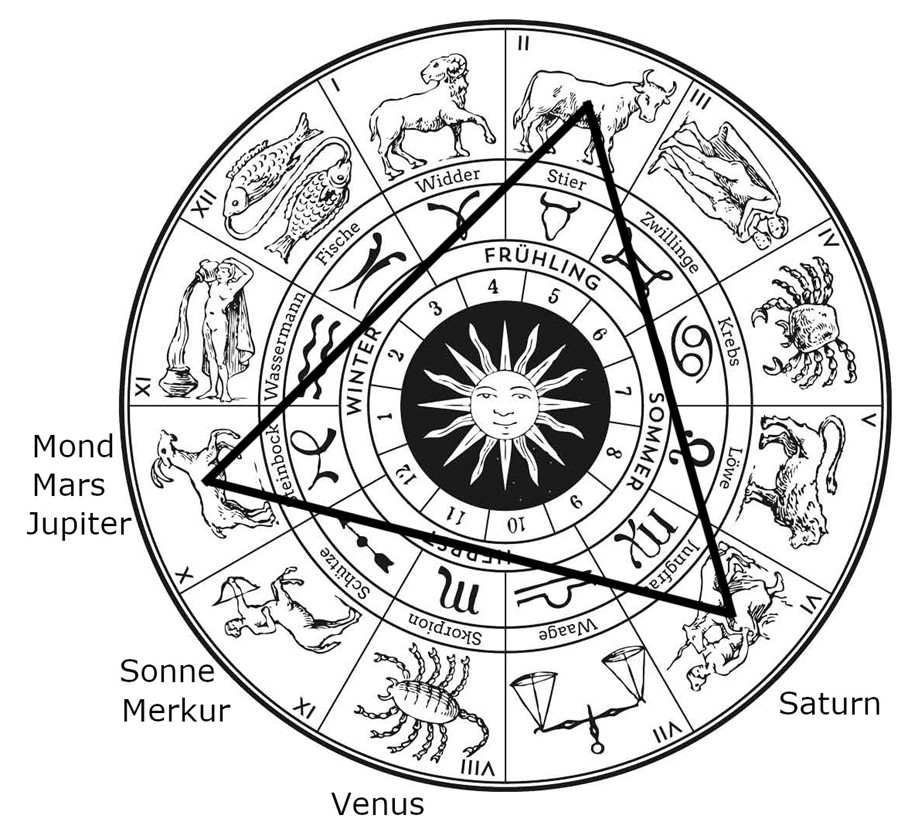

The spread of the Babylonian zodiac[i] is difficult to map with precision. By the time its presence is certain and explicit, the reception is already well-advanced. There are hints suggesting that it had been circulating in some form before catching the attention of the few writers whose works are extant. For instance, evidence from Egypt shows representational and computational influences early on.[ii] The case of the ancient Greek reception is interesting as well. It would seem reasonable to assume that Alexander’s subjugation of the Achaemenid empire fostered – or forced – exchanges between the two cultures. But there is a double problem with this assumption: firstly, exchanges had already taken place before that,[iii] although it is not clear whether it included astrological and/or astronomical knowledge relating to the Babylonian zodiac, nor to which extent. Secondly and conversely, we do not have unambiguous textual evidence of the uniform zodiac in Greek texts before the Phenomena of Aratus of Soles anyways,[iv] i.e. ca. 50 years later.

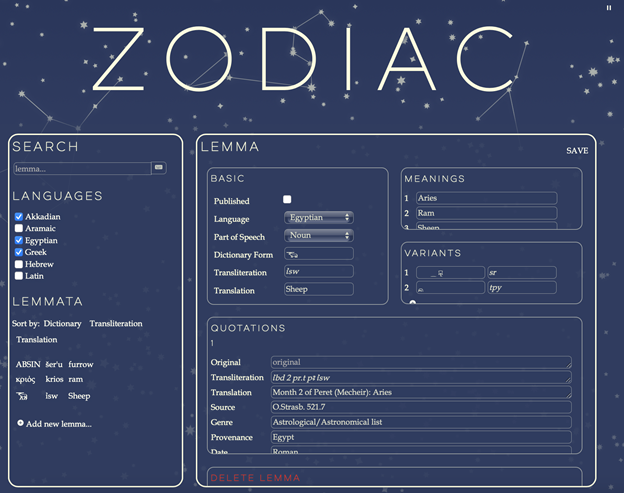

Where could we find echoes of its presence? My exploration project at the CHRONOI center and in close collaboration with ZODIAC aimed at addressing one particular case of a potential reaction to the zodiac, in particular the Babylonian uniform zodiac.

The Letter to Pythocles is a textwritten at the beginning of the 3rd century BCE probably by the famous ancient philosopher Epicurus (ca. 340–270 BCE), or at the very least by his entourage. Despite the title, the text is more of a doctrinal breviary than a proper letter. It deals with many traditional atmospheric, celestial, astronomical and natural phenomena (shooting stars, hail, rainbow, etc) for which Epicurus offers one or more explanations in a heavily summarised form.[v] They all have in common that they do not require the gods’ intervention. A convinced atomist, Epicurus thought it better, i.e. more pleasurable, to support a mechanistic understanding of the world’s events with no meddling from divine power(s). For such interferences could induce the fear that happiness might not be up to us but rather dependent on the discretion of superior entities. This would be fatal to his philosophical therapy based on the somewhat optimistic yet empowering premise that happiness is always at hand.

Given the strong reductionistic drive behind the composition of the Letter and the fact that it was explicitly meant to be a vade-mecum to help the readers remember more easily complex matters, it is striking that we should find a topic seemingly treated twice with a similar if not identical wording. The two passages deal with the so-called episemasiai, i.e., the indications or signs given by certain phenomena that forecast upcoming seasonal or climatic changes. In both, Epicurus is concerned with the behaviour of ‘animals’ and in particular with their causal power:

- Epicurus, Ep. Pyth. 98–9 (Dorandi)

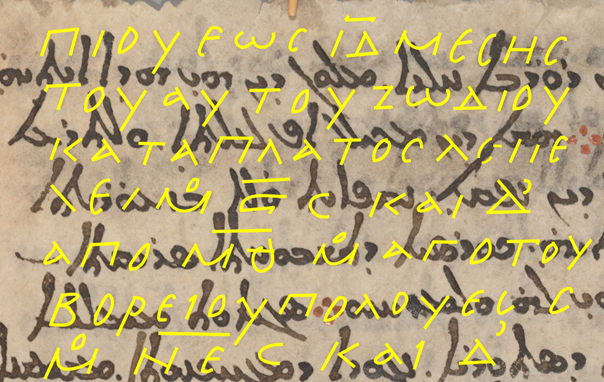

ἐπισημασίαι δύνανται γίνεσθαι καὶ κατὰ συγκυρήσεις καιρῶν, καθάπερ ἐν τοῖς ἐμφανέσι παρ’ ἡμῖν ζῴοις, καὶ παρ’ ἑτεροιώσεις ἀέρος καὶ μεταβολάς. ἀμφότερα γὰρ ταῦτα οὐ μάχεται τοῖς φαινομένοις· [99] ἐπὶ δὲ ποίοις παρὰ τοῦτο ἢ τοῦτο τὸ αἴτιον γίνεται, οὐκ ἔστι συνιδεῖν.

“Indications [sc. of season/weather] can occur both according to the coincidences of the moments, as for the animals visible around us, as well as by an alteration and modification of the air. For neither of the two possibilities is against the phenomena. But it is impossible to know in what circumstances the cause comes from one or the other.”

- Epicurus, Ep. Pyth. 115–6 (Dorandi, adapted)

αἱ δ’ ἐπισημασίαι αἱ γινόμεναι ἐπί τισι ζῴοις κατὰ συγκύρημα γίνονται τοῦ καιροῦ. οὐ γὰρ τὰ ζῷα ἀνάγκην τινὰ προσφέρεται τοῦ ἀποτελεσθῆναι χειμῶνα, οὐδὲ κάθηταί τις θεία φύσις παρατηροῦσα τὰς τῶν ζῴων τούτων ἐξόδους κἄπειτα τὰς ἐπισημασίας ταύτας ἐπιτελεῖ. [116] οὐδὲ γὰρ εἰς τὸ τυχὸν ζῷον, κἂν μικρῶ χαριέστερον ᾖ, ἡ τοιαύτη μωρία <μὴ> ἐκπέσῃ, μὴ ὅτι εἰς παντελῆ εὐδαιμονίαν κεκτημένον.

“But the indications that occur ‘on the occasion of certain animals’ happen according to the coincidence of the moment. Because the animals cannot force the coming of bad weather and no divine nature orders the exits of these animals and then accomplishes what they indicate. For such nonsense should not come to the mind of any random animal, including those who are rather smart, and even less of that which possesses complete happiness [i.e., the gods].”

In the first passage Epicurus specifies that those animals are among us, par’ hêmin. This suggests that he means actual animals, whose appearances coincide with, say, the arrival of spring. However, in the second one, the animals are not thus qualified. Could it be that Epicurus refers to another kind of animals, namely zodiacal ones?[vi]

There are, at first sight and broadly speaking, several arguments speaking in favour of such an interpretation. First, it would nicely fit the overall topics of the letter, which does not mention animals elsewhere. Second, it would account for, and diminish, the repetitive character of the two passages. Third, we know of an Epicurean rivalry with another school of natural philosophers following Eudoxus of Cnidus’ doctrine in Cyzicus. Since Eudoxus (ca. 390–340BCE) wrote i.a. on sidereal cycles, it could be tempting to read here a criticism of Eudoxus observation of constellations. What is more, the recipient of the letter, Pythocles was in Lampsacus, i.e. geographically close to Cyzicus.

However, the reality is more complex. While still supporting an anti-astrological reading of the passage, my research has led me to distance myself from a strictly zodiacal reading and to discard the Babylonian geometric zodiac as a source altogether. In other words, although there is a clear rejection of astrology as a technique for inferring future events and possibly a rejection of more particular interpretations relating to the behaviour of certain constellations, there is, I think, no reason to limit Epicurus’ argument to zodiacal constellations only, let alone to the 30°-signs of the uniform zodiac. But let us first briefly review the preceding arguments.

The first argument, namely that this text does not mention animals elsewhere, applies only limitedly to a letter dealing with so many different topics. Furthermore, it would not explain the oddity of the first episemasiai, which unambiguously speak of terrestrial animals. Besides, we have testimonies (also in astronomical contexts)[vii] attesting to the observation and interpretation of real animals’ behaviours. The second argument, namely that it explains what would otherwise look like a near repetition, is a bit circular: for such a differentiation to be a solution, we must first assume that repetitions are problematic – which they evidently need not be, given that the text is replete with methodological comments which echo each other in nearly identical forms at the ends of most entries. The third argument is fairly weak too: the evidence that Pythocles was actually interested in Eudoxus’ school is poor at best[viii] and Eudoxus does not seem to have been particularly interested in zodiacal signs for the sake of predictions.[ix]

The first set of arguments is thus not conclusive. And it could be added to this that zodia is the regular word to describe zodiacal signs, whereas zoa is attested only much later with that sense (with Anubion or maybe even Manetho, i.e. in imperial times). But, of course, this too is slightly circular.

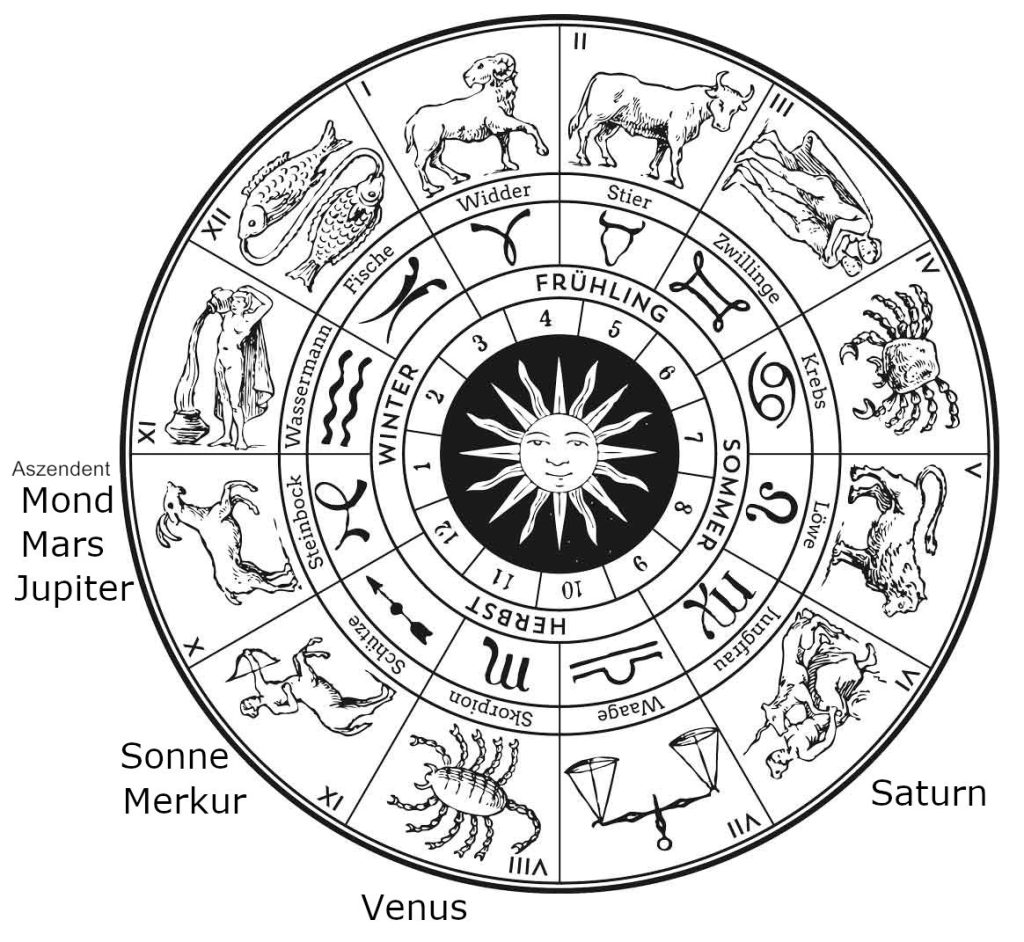

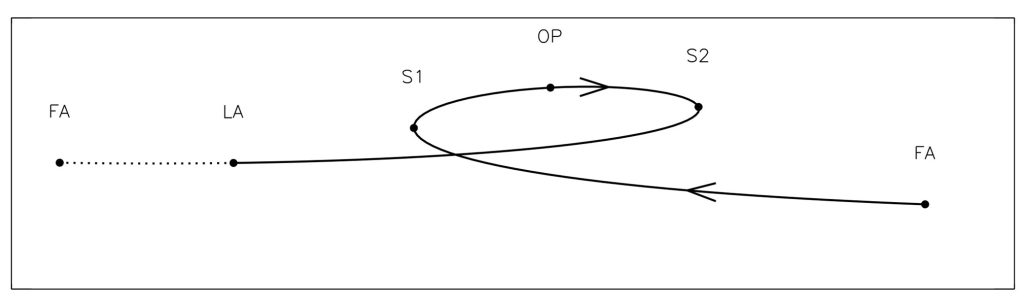

Let’s go back to the differences between the episemasiai, building on the par’ hemin. I mentioned before. In the first passage, the behaviours of animals en gros are mentioned parenthetically as one example of coincidental, i.e. non-causal, correlation when it comes to atmospheric or seasonal changes, just like a gush of wind might precede a weather change without being the cause for it. The second passage, on the other hand, aims at something slightly different. The re-affirmation of the fortuitous and meaningless character of animals is more precise (Epicurus speaks of “certain”, tisi,animals and their “outgoings” or “exits”, exodous) and they are not mentioned as a mere example of the misinterpretation of coincidences anymore. The fact that Epicurus focuses on the exit of certain animals suggests that he is thinking of zoa that are not visible all year round. This may seem misleadingly significant to some people, but it is actually “random” (tuchon) accordingly to Epicurus. Making certain zoa causally or at least symbolically significant depends on an arbitrary correlation of fortuitous phaenomena. Furthermore, a new element comes up in addition to the absence of causal power in animals, namely the fact that no “divine nature” (theia phusis) would bother to make animals do their biddings (gods don’t care anyway). This second aspect is completely absent from the first episemasiai. Finally, the ‘animals’ of the second episemasiai almost endorse something of a temporal status with epi (unlike en), which I translated with “on the occasion of”. This is reinforced by the following sugkurema tou kairou, i.e., a “coincidence of the moment”.

All this serves an anti-astrological interpretation well.

Indeed, the meaning of astral conjunction for sugkurema is unproblematic, and exodos in the more technical sense of anatolê (i.e. the rising of an asterism) is plausible. Besides, in both cases, using ambiguous and more generic or non-technical terms could easily serve a derogatory purpose. We can also add that the attitude consisting in hesitating between making stars either living entities endowed with power themselves, such as gods, or mere representations or symbols or tools of the gods – these are in effect the two options offered by Epicurus – fits quite well with the very understanding of stars at that time, hesitating between referential representations or symbols of the gods on the one hand, and sacred entities in their own rights on the other.[x]

Epicurus seeks to deny the causal efficacy of the stars, which include planets, and the significance of their motion even if we cannot explain exactly how it works. But one might argue that by using zoa, literally “living being”, Epicurus runs the risk of animating the asterisms, which would make it hard for him to criticise their traditional ontological status and the predictive semiotic wrongly attached to it. In order to defend an astrological reading of the second episemasiai, one needs to assume that we are facing a counterfactual statement, for stars are not zoa in the first place according to Epicurus. They are neither divine nor animate. But even if they were – so Epicurus – the reasoning would not work. Entertaining an irreligious ambiguity between terrestrial animals and what some people consider to be divine celestial entities could thus prove argumentatively and philosophically coherent – more so than if he had used zodia.[xi]

In sum, if the animals of the first episemasiai must be terrestrial ones appearing around us, the second zoa are more equivocal – possibly deliberately and, I think, productively so. Epicurus does not need either the geometric division of the ecliptic into twelve 30° signs, as elaborated by the Babylonians, or even the zodiacal constellations in them in particular. But an anti-astrological reading makes good, and maybe better, sense in the context of the second episemasiai than considering them a mere reformulation of the first ones. The arrival of the Babylonian zodiac in Greece during or around his lifetime and a growing interest for the “foolish” astrology and the seemingly erratic path of the planets might well have caught his attention.[xii] Given his focus on the removal of divine interference and on building sober hermeneutics when facing distant and unclear phaenomena, Epicurus must have felt the need to react. Stoics approached the matter quite differently – but that’s another story.

References

Bakker, Fredrik A. (2016): Epicurean Meteorology. Sources, Method, Scope and Organization, Brill: Leiden/Boston.

Bollack, Jean / Laks, André (eds.) (1978): Épicure à Pythoclès. Sur la cosmologie et les phénomènes météorologiques, Publications de l’Université de Lille: Villeneuve d’Ascq.

Britton, John P. (2010): “Studies in Babylonian Lunar Theory: Part III. The Introduction of the Uniform Zodiac”, in Archive for History of Exact Sciences 64, pp. 617–663.

Hannah, Robert (2020): “The Moon and the Planets in Classical Greece and Rome”, in: Oxford Research Encyclopedia. Planetary Science, Oxford: OUP, DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190647926.013.196

Hoffmann, Friedhelm (2017): “Astronomische und astrologische Kleinigkeiten VII: Die Inschrift zu Tages- und Nachtlängen aus Tanis”, in R. Jasnow / Gh. Widmer (eds): Illuminating Osiris. Egyptological Studies in Honor of Mark Smith, Atlanta: Lockwood Press, pp. 135–153.

Lasserre, François (1966): Die Fragmente des Eudoxos von Knidos, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

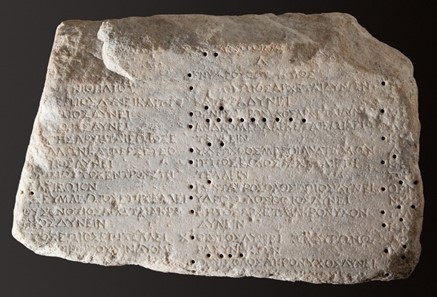

Lehoux, Daryn (2020): “Image, Text, and Pattern: Reconstructing Parapegmata”, in A. Jones/C. Carman (eds.): Instruments – Observations – Theories. Studies in the History of Astronomy in Honor of James Evans, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3928498.

Oll, Moonika (2015): Greek ‘Cultural Translation’ of Chaldean Learning, diss., University of Birmingham.

Rochberg, Francesca (2010): “Babylonian Astral Science in the Hellenistic World: Reception and Transmission” in Center for Advanced Studies. Ludwig-Maximilian-Universität München. Eseries 4 – https://www.cas.uni-muenchen.de/publikationen/eseries/cas_eseries_nr4.pdf

Sedley, David (1976): ‘Epicurus and the Mathematicians of Cyzicus’, in Cronache Ercolanesi 6, pp. 23–54. Verde, Francesco (ed.) (2022): Epicuro. Epistola a Pitocle, in coll. with Mauro Tulli, Dino De Sanctis, Francesca G. Masi, A

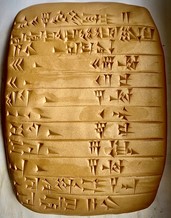

[i] I use here “Babylonian zodiac” to refer to the so-called “uniform zodiac”, i.e. the division of the ecliptic into twelve equal 30° sections named after the constellations they originally contained. This analytical framework was developed during the Achaemenid period and securely attested from the late 5th century BCE – see Britton 2010. For an overview of the Greek reception of Babylonian (or “Chaldean”) astronomy, see Rochberg 2010.

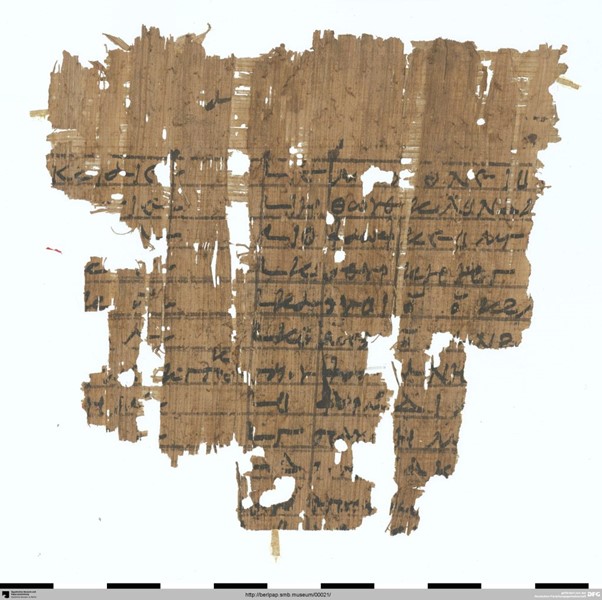

[ii] Cf. Hoffmann 2017; see also Oll 2015, p. 188–199.

[iii] Cf. Aristotle, De caelo 292a (ca. 350 BCE). We know through ancient testimonies that several Greek and Greco-Babylonian authors from the 5th to 3rd century BCE such as Berossus, Callipus, Euctemon, Eudoxus, or Meton were strongly interested in astronomy. But too much has been lost to ascertain their take on the constellations on the ecliptic with certainty. Demetrius I Poliorcetes, king of Macedon from 294 to 288 BCE, is reported to have worn a garment with the twelve signs of the zodiac on it (cf. Athenaeus, Deipn. 535f–536a).

[iv] It seems that Aratus’ knew of the twelves signs as a geometric division of the ecliptic as inherited from Babylon, but he did not really understand it, judging by his own admission (Phaen. 460–461). Note that wars and conquests do not necessarily foster the best environments to share knowledge.

[v] Epicurus relied considerably on earlier sources, e.g., the so-called Syriac meteorology and Theophrastus. See Bakker 2016, 76–161.

[vi] This had been suggested en passant a few times until Bollack and Laks’ commentary (1977, ad loc.), although recent research favours the opposite direction (Verde 2022, 252–3). The topic has not got the attention it deserves to this date.

[vii] E.g., the end of Aratus’ Phaenomena (vv. 733ff.), and the somehow-related On Signs ascribed toTheophrastus.

[viii] Sedley 1976. 43–7, esp. 46.

[ix] Cf. Lasserre 1966. Fragmentary though the remnants are, it is clear that Eudoxus was aware of the ecliptic and of the constellations that are on it. However, this much is nothing exceptional; we actually get it from earlier parapegmata (cf. Lehoux 2020, 109) and it was maybe known to Cleostratus, i.e., as early as in the 6th century BCE, according to Pliny the Elder (NH II 30–31).

[x] The hesitation was probably reinforced by the arrival of Babylonian astronomy. Around the 4th century BCE, the planets started taking on the names of gods and being their attribute while becoming increasingly assimilated linguistically as well (« Hermes’ star » becoming « Hermes » tout court). See Hannah 2020.

[xi] The terms semeia or semata which are regularly used for constellations would generate an unfortunate ambiguity in a context where we are dealing with epi-semasiai. As to the other terms often used, eidos or eidolos, Epicurus had good reasons not to use them; it is a very technical term in his theory of perception (the Lucretian simulacra) referring to the atomic films emanating from objects and hitting our sensory apparatus.

[xii] Epicurus, Ep. Pyth. 112–113.