17 February 2022, by Marvin F. Schreiber

Melothesia is an astrological concept of assigning human body-parts to celestial objects that was extant in Greco-Roman astral science. Its conceptual background was the assumed sympathy between macrocosm and microcosm. The limbs were often assigned to zodiacal signs, the internal organs to

planets. It was mainly used in astrological medicine, e.g. to find the assumed heavenly origin of a disease via the affected body part. Different systems of assignment existed side by side, named after the category of celestial object to which the body is connected: decanal, planetary, and zodiacal melothesia.

Decanal melothesia is of Egyptian origin (decans, subdivisions of signs into three parts, are an element of Egyptian astrology). The first securely dated attestation of zodiacal melothesia in Greco-Roman astrological literature is in Manilius, Astronomica (1st century CE); but there is evidence that the zodiacal form, as well as the planetary, was developed in Babylonia.

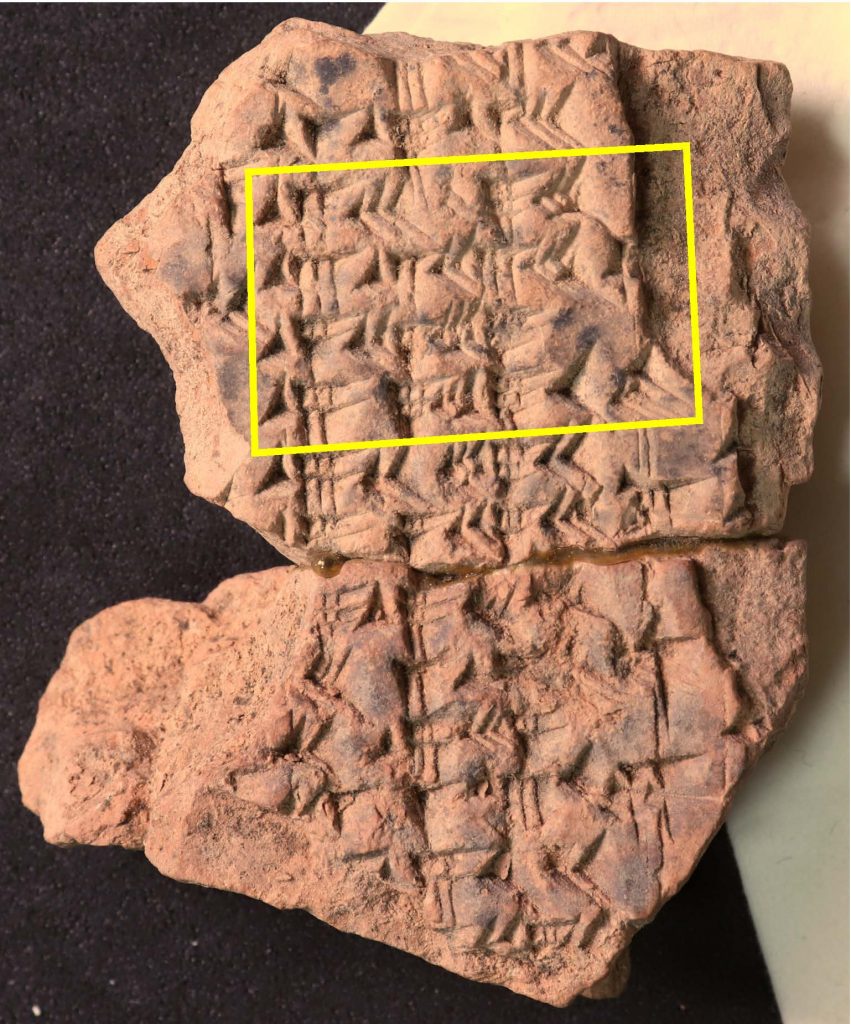

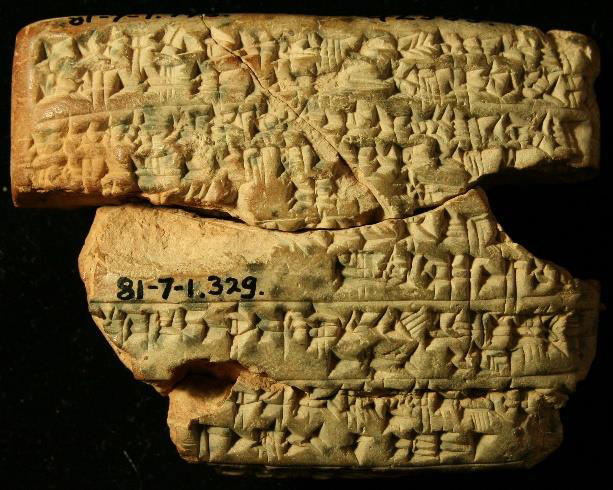

With a uniform structure such as the twelve divisions of the zodiac, introduced in Late Babylonian astral science in the late 5th century BCE, it became possible to connect the body and the stars in a systematic way. The structure of the zodiac was mapped onto the human anatomy, dividing it into twelve regions, and indicating which sign rules over a specific part of the body. The ordering is from head to feet, respectively from Aries to Pisces. The main document that contains the original Babylonian melothesia is the astro-medical tablet BM 56605. The text can be dated roughly between 400–100 BCE.

The obverse contains a section that resembles the 29th tablet of the diagnostic-prognostic omen series Sakikkû and subsequently a text about twelve stars that are affecting specific body-parts by “touching” them, each followed by a remedy. This text could be seen as a pre-zodiological stage of melothesia.

The tablet’s reverse also consists of two sections: one column on the right contains an astro-medical zodiac scheme (‘stone-plant-wood’ for each sign) in combination with a hemerology, on the left (roughly three quarter of the tablet’s reverse) follows a micro-zodiac table.

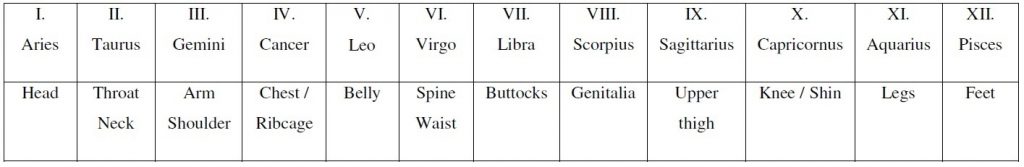

The top row of the table consists of twelve squares with the zodiacal signs, below that an equal row with the assigned body-parts. Underneath each sign and body part are vertical sub-columns of squares with the names of animals, accompanied by numbers (referring to the micro-signs). The sequence of body parts in this text was first identified by J. Z. Wee in 2015, who uses the term ‘zodiac man’ for it.

The arrangement is the following:

Another thing that points to a Babylonian origin of melothesia is that the zodiacal form itself already had its forerunner in calendrical melothesia. It can be found in a group of medical texts from Sippar (northern Babylonia) dating to the late 6th or early 5th century BCE, and therefore older than the zodiac. In this form the body-parts are assigned to the twelve months of the Standard Babylonian Calendar.

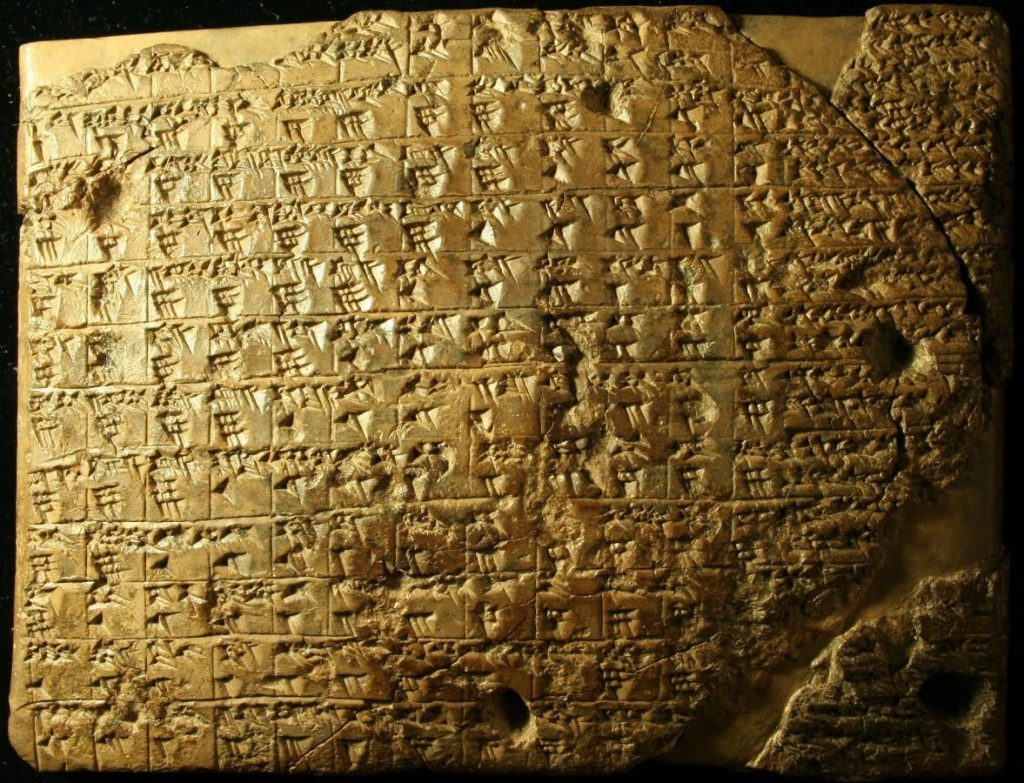

There are four fragmentary tablets that could be used for a reconstruction of calendrical melothesia: BM 43558+, BM 42385, BM 42407, and BM 42655.

The first three of these texts treat the body-parts in their associated months and describe a therapy for each: ointments with oils, animal fats and healing stones, herbal potions, and short ritual instructions; although a diagnosis is never mentioned. BM 42655 is somewhat different: the text mentions certain

days, together with a stone-plant-wood-scheme that is identical with the zodiacal scheme that appears in the right column on the reverse of BM 56606 (see above). What follows is a sequence of body-parts which is in accordance with the calendrical melothesia documented in the other texts. The calendrical melothesia from the Sippar texts is the forerunner to Late Babylonian zodiacal melothesia, what shows that such a form of healing dates back at least to the late 6th century BCE, and is most likely of Babylonian origin.

The following table is a comparison of the reconstruction of calendrical and zodiacal melothesia.

| Calendrical Melothesia Logogram (Akkadian) | Zodiacal Melothesia | |

| I | IGI.MEŠ (pānū), SAG.DU (qaqqadu) Face and head. | SAG.DU Head. |

| II | GABA (irtu), GÚ (kišādu) Chest and neck. | ZI (napištu) GÚ Throat and neck. |

| III | ŠUII (qātā) Hands. | Á (aḫu) MAŠ.SÌL (naglabu) Arm and shoulder. |

| IV | TI.MEŠ (ṣelānu) Ribcage. | GABA/TI.MEŠ (?) Chest/Ribcage. |

| V | ŠÀ (libbu) Belly. | ŠÀ Belly. |

| VI | GÚ.(MURGU) (eṣemṣēru) MURUB4 (qablu) Spine and waist. | GÚ.MURUB4 Spine and waist. |

| VII | (…) | GU.(DU) (qinnatu) Buttocks. |

| VIII | (…) | PEŠ4 (biṣṣūru) Female Genitalia. |

| IX | maḫirtu maḫirtu-leg(bone). | TUGUL (gilšu) Upper thigh. |

| X | DU10.GAM-iṣ (kimṣu) Knee/shin. | kimṣu Knee/shin. |

| XI | ÚR.MEŠ (pēnū) Legs. | ÚR Leg(s). |

| XII | ŠUII.MEŠ (?) ‘Hands’ (error for ‘feet’?). | GÌRII (šēpā) Feet. |

An arrangement of body parts ‘from head to feet’, this scheme, in Akkadian known as ištu muḫḫi adi šēpe, was also used, e.g. in the diagnostic-prognostic omen series Sakikkû. As mentioned above, the obverse of BM 56605 contains some diagnostic omens that resemble omens from Sakikkû. A sequence of twelve tablets (tablets 2–14) of this series is ordered according to the scheme ‘from head to feet’, what maybe inspired the later concept of melothesia in combination with the twelve months or the twelve signs.

Further reading:

Schreiber, M. F. (2019) ‘Late Babylonian Astrological Physiognomy’ in Johnson, J. C. and Stavru, A. (eds.) Visualizing the invisible with the human body: Physiognomy and ekphrasis in the ancient world (Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures 10). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 119–140.

Wee, J. Z. (2015) ’Discovery of the Zodiac Man in Cuneiform,’ Journal of Cuneiform Studies 67, 217–233.

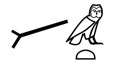

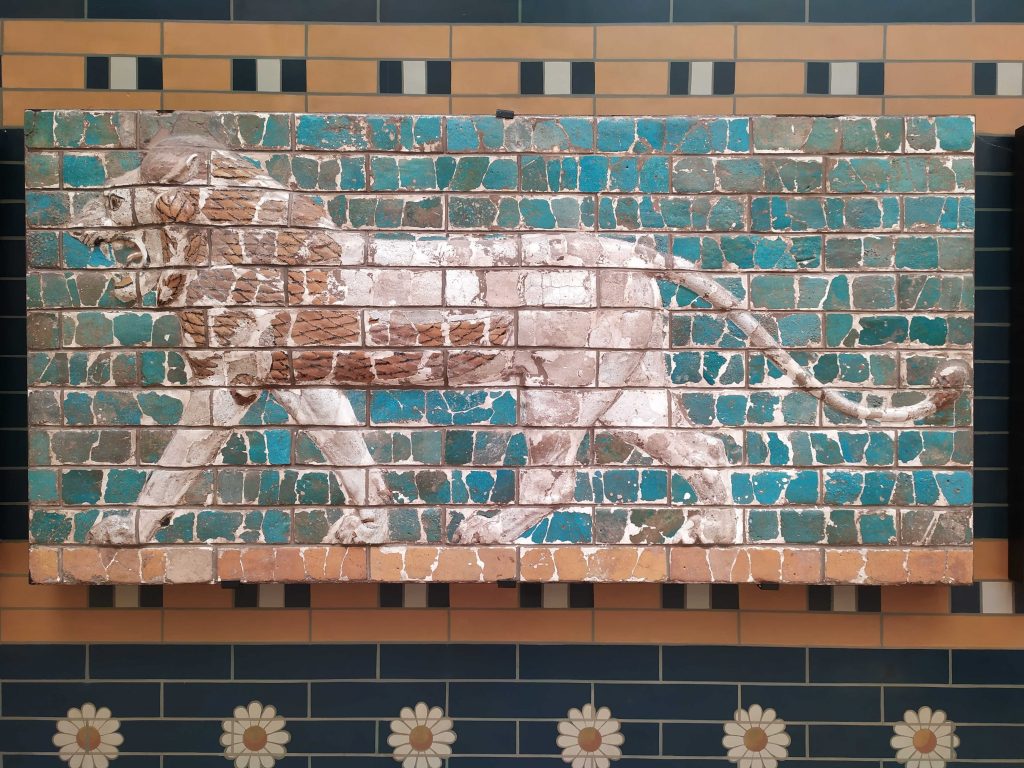

, a man lifting up his arms, can be understood as representing the two raised arms of the ka-hieroglyph

, a man lifting up his arms, can be understood as representing the two raised arms of the ka-hieroglyph  , which could be used to write the Egyptian word for bull. Saturn’s name in Egyptian is “Horus the Bull”. A more complex example is the representation of Mercury, which was associated with the god Thoth, by the heart hieroglyph (

, which could be used to write the Egyptian word for bull. Saturn’s name in Egyptian is “Horus the Bull”. A more complex example is the representation of Mercury, which was associated with the god Thoth, by the heart hieroglyph ( ) . The heart also represents this god. Thoth was often called the heart of the sun god Re, and in contemporary temple inscriptions the word for heart can be written with the hieroglyphic sign of the ibis, one of the animals connected to Thoth. If the heart can be written with the ibis, the bird and thus the god it represents can be written with the heart.

) . The heart also represents this god. Thoth was often called the heart of the sun god Re, and in contemporary temple inscriptions the word for heart can be written with the hieroglyphic sign of the ibis, one of the animals connected to Thoth. If the heart can be written with the ibis, the bird and thus the god it represents can be written with the heart.

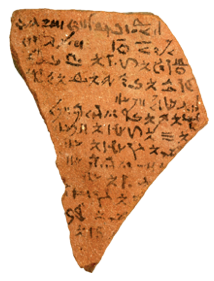

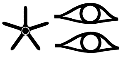

) instead of “Ram”, the more common designation for the sign. Gemini could be written with two eyes (

) instead of “Ram”, the more common designation for the sign. Gemini could be written with two eyes ( ), as in the illustrated example, or with two eyebrows (

), as in the illustrated example, or with two eyebrows ( ): the two eyes recall the divine twins Shu and Tefnut, who can be referred to as the two eyes of the sun god. A third example relates to Cancer (not preserved on the ostracon). Most other horoscopes spell out the name of the sign or abbreviate it, but the present text represents it with the hieroglyph of a spine with ribs (

): the two eyes recall the divine twins Shu and Tefnut, who can be referred to as the two eyes of the sun god. A third example relates to Cancer (not preserved on the ostracon). Most other horoscopes spell out the name of the sign or abbreviate it, but the present text represents it with the hieroglyph of a spine with ribs (