20. March 2013 von Melanie Klein

Interview with curator and art critic N’Goné Fall on the situation of women artists from Africa …

The Soapbox: In your article for Global Feminisms from 2007 you wrote about the role of women still being restricted after most African states achieved independence in the 1960’s. How did women perceive this phase? Have there been women who were disappointed about the continuation of their roles? What about women in Dakar, for example?

N’Goné Fall: Well, some were frustrated, others “trained to be a perfect mother and wife” accepted their position in the society. Things started to change in the mid 1970s and early 1980s with the modernization of cities and new life style. Some women had a job (after having a high education at university), financial independence, access to Western theories and started questioning their own society. It started with writers mainly and at large we could say with women intellectuals. And it all happened in big cities, mainly in the capitals. In Dakar, the first “hit” was the novel Une si longue lettre by Mariama Bâ. The book is still a landmark in Senegal. But in the visual arts world nothing really changed as the few women who were practicing art were involved in decorative things.

Please note that I am talking about a continent. Yet, some countries – Egypt and South Africa, for example – had a feminist movement and women artists with clear positions.

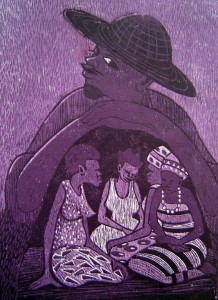

TS: Addressing silence and invisible struggles of women in the African context in contrast to feminist movements in Europe and the U.S. is still crucial. How do you reflect different artistic strategies of visibility in this respect in the work of Bill Kouélany, for example, or, more recently, Zanele Muholi and Mary Sibande?

NF: Bill Kouélani does not see herself as a feminist even if she is a though women and the only female artist known from Congo. Her work is very strong, deals with various issues but she does not have “an activist strategy”. For sure, Zanele Muholi is an activist as a person and as an artist. All her work is about the place of gays, lesbians and transgender people in the South African society. And it did help raise, debate and advance the case of minorities in her country and abroad. The photographs do not let any space for misinterpretation: it is about sex and gender, love and life.

The work of Mary Sibande is less obviously activist at a first look. But it is definitively about racial and social classes as well as about the position of women in the South African society. Some people would see it as nice and poetic dreams of a black woman. But there is no doubt that her work is about race, gender and the social position of minorities in her country.

TS: Several female artists from the African continent seem to work in a difficult space between asserting their culture against stereotyping or hegemonic interpretations and coming to grips with gendered restrictions of exactly these cultural structures as, for example, Zineb Sedira. Artistically, the exposure to this double ‘forefront’ produces important statements on the ambivalent nature of women’s situation. Could you specify to what extent these statements enlarge the “space of freedom” for women you are writing about without being “seduced by global discourses”?

NF: The younger generation of women artists from Africa is aware of the “game in the global art world”. They are also aware that being from Africa can sometimes open doors and offer opportunities as institutions want to be truly international and inclusive. Some of these artists have a double culture with parents from one continent and themselves from another one. They all decided not to play the victim card but rather to embrace their multiple cultures and look at the world from various perspectives and reference points. Their works are often refreshing, questioning societies and have sometimes different meanings. They all benefited from the achievement of feminist struggles, travel quite a lot and are open to multiple cultures. Their works are about the world today, about the local and the global, about societies. And they do not only focus on women issues to highlight the cause of women. Very clever strategy.

TS: Thank you very much, dear N’Goné, for taking the time to give us this overview.

Literature: N’Goné Fall (2007): “Providing a space of freedom. Women artists from Africa“, in: Maura Reilly and Linda Nochlin (eds.), Global feminisms. New directions in contemporary art, London, Merrell Publishers.

Die

Die