At the moment, when thinking about all the languages in Belize, I actually start to think that the most fascinating aspect is that Kriol is the oral lingua franca, which is nevertheless rejected as a language of writing, high culture and education.

So far, almost everyone I interviewed, either in a more formal and recorded interview or on the streets, told me that they use Kriol with their friends (some among Spanish, English, Garifuna, Mopan or Ketchi). Some of the older say that they do not speak Kriol but say they speak English or insist that they use ‘broken English’, but from the way they talk to me, it is very obvious that they do speak what younger people call Kriol. For these speakers, the British legacy seems important. Actually, the two older men who insisted on not speaking Kriol but English or broken English both complained about the ‘Alien’ ‘Spanish’ people (who probably have been a demographic majority since the middle of the 19th century). In one case, this older man actually spoke Spanish at home.

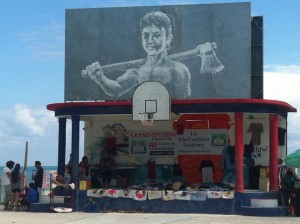

Anyhow, the question is: Why do people learn Kriol? Speakers who do not use it at home learn it on the streets and in school, from their peers, although their native languages, particularly if it is Spanish (English as home language is a rare exception), is a widely used prestigious standard world language. So why is it that Kriol has this prestige, although it is not officially mediated, neither in education nor in public media? It does not seem to be an effect of strong contemporary ties with Jamaican youth culture (which I thought to be possible). There is this a historical, cultural and musical link to Jamaica but using Jamaican features is not common among Belizeans, only among those who adhere to Jamaican Reggae music and want to show this. So, coming back to the original question of where the popularity of Kriol comes from, it is important to observe that although Mestizo Spanish-speakers tend to see themselves as being superior to black Creoles – the issue of racism is mentioned frequently in my interviews, which is constructed simply in terms of shades of skin colour – they all learn Kriol. This, I think, may be explained with a look at political history. Clearly, the English language was implemented in Belize by the British but it was only the elite (called Royal Creoles by some, lighter in skin and descending from British males directly) who learned English, either in families or in school. The rest would not have access to English but only to Kriol and, potentially, their other native languages. Today’s relative prestigious status of Kriol may have to do with the, in relative terms, equal (compared to other slave societies) status of slaves, which people explain to me with the fact that male Belizean slaves did not work on plantations but were woodcutters, using sharp instruments to do that, so having a weapon at hand.

The myth of a brotherly relationship between white slave masters and their black co-workers has been only mentioned to me by white rich Belizeans, and, as a matter of fact, history books on Belize will have enough examples of the desperate and right-free situation of slaves. Yet, considering the work practices of Belizean slaves, it may make sense to say that the position of slaves in Belize was different compared to slaves in plantation colonies. The most crucial factor, however, is probably that members of the Creole group (people of mixed African and European descent) were given posts by the British, first as supervisors during slavery, then as leaders of political administration before independence, in jobs as lawyers, politicians, public servants and so on. The political elite of Belize, therefore, before and after independence, was Creole. This remains so today in the Belize district, where is the biggest town – Belize City. Yet, this still does not answer why Kriol has such a strong position in Belize, so strong that not only Creoles keep it but that all other groups learn it. It could have been English, the language of education, media, the government and of more or less everything that is written in Belize.

Do people here feel the need to maintain a linguistic safe zone? Is this linked to the colonial history, a desire to be different from the British and the Americans? Will this explain why Kriolis mostly rejected as a language for standardisation and for writing? Is it simply a national community-building tool that is available only to the ‘born-and-bred’ Belizean? It is all the more interesting that by now several people have told me that there are different varieties of Creole that seem to differ according to location but also according to race. I think that this is the right spot for a study on language ideologies!

Die

Die