04. Januar 2022, by Andreas Winkler

The practice of astrology in Graeco-Roman Egypt was largely bilingual. Nevertheless, as in many other areas, the documentation in Greek often appears to be more abundant and diverse than that in Egyptian. The published Greek horoscopes cover a wider chronological span and appear to have a wider range of complexity, from simple to elaborate, while the Egyptian horoscopes published to date are generally rather simple. In this blog post, however, I will show that this was not always the case.

Simple horoscopes could be produced by relatively unskilled practitioners. They contained only the most rudimentary data that an astrologer needed to complete his task: the positions of the five planets known in antiquity (Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury) plus the Sun and the Moon, which were pinpointed in relation to whole zodiac signs. Whether Greek or Egyptian, a horoscope often provides the date and time of birth, specified down to an hour. The birth hour was needed to determine the rising sign, a last crucial piece of information. A new sign rises above the horizon roughly every second hour. From this sign the “Twelve Places”, each one being equivalent to one zodiac sign, were established. Briefly put, they were thought to govern various areas of a human life, and if a planet was found in one, it impacted this particular aspect.

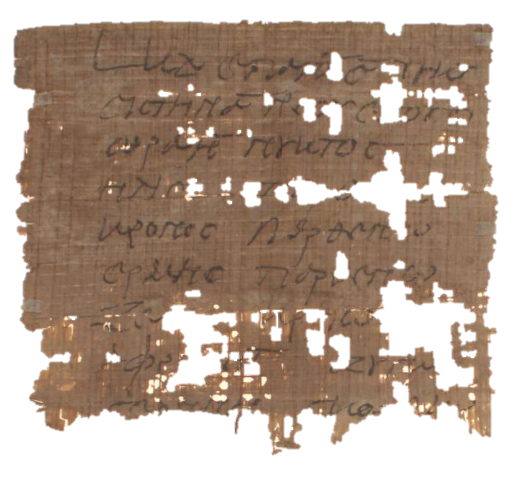

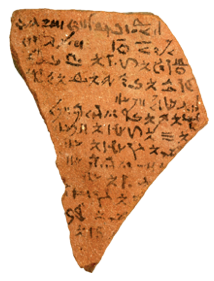

Some horoscopes provide a more detailed specification of the planetary positions at the moment of birth. The planets can be located down to the degree or even arc minute in a sign. This opens up the possibility to describe further relations of the celestial bodies that could be useful for interpreting someone’s future. Most of these more advanced horoscopes are in Greek, but there are also a few Egyptian examples. O.Ashm.Dem. 633 is a fragmentary potsherd (ostracon) with a text written in hieratic and demotic, published by Otto Neugebauer and Richard A. Parker in 1968.[1] Due to its slightly idiosyncratic nature and incomplete state of preservation, the content of this horoscope was not fully understood in the first edition. Some years ago, however, I had the good fortune of finding a few additional examples of such texts in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. They have helped me to refine the interpretation of the horoscope.

Unlike most other horoscopes, the piece provides what seem to be two dates (ll. 1–2 and 5). The first places the birth in year 8 of the Queen (Cleopatra VII), day 22 of the month of Pharmuthi (April 22, 44 BCE). The positions of the celestial bodies given next (ll. 3–4 and 6–10) fit the date well, which makes the horoscope one of the oldest from Egypt. That Cleopatra VII is referred to with her title only, however, suggests that the text was written after the Roman conquest.

The second date mentions a year 13. This refers to a year in the 25-year lunar cycle (the time it takes for the Moon to reach the same relative position to the Sun on the same day). The lunar cycle had begun in 57 BCE and the birth fell in its 13th year. The reason for adding this information must have been to more easily pinpoint lunar positions, such as syzygies (opposition or conjunction), important for the horoscope.

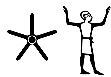

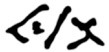

What distinguishes the horoscope from other Egyptian ones is not only its richness of detail but also the way the names of the planets, zodiac signs, and other entities are written. Instead of writing out the full names of the planets, which is a common practice in other horoscopes, only one sign was used. Although this practice is already known from astronomical texts and even horoscopes, the set of signs used in the present set of texts deviates to some extent from other texts. For instance, the sign used to write Saturn  , a man lifting up his arms, can be understood as representing the two raised arms of the ka-hieroglyph

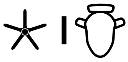

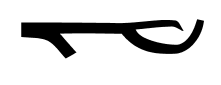

, a man lifting up his arms, can be understood as representing the two raised arms of the ka-hieroglyph  , which could be used to write the Egyptian word for bull. Saturn’s name in Egyptian is “Horus the Bull”. A more complex example is the representation of Mercury, which was associated with the god Thoth, by the heart hieroglyph (

, which could be used to write the Egyptian word for bull. Saturn’s name in Egyptian is “Horus the Bull”. A more complex example is the representation of Mercury, which was associated with the god Thoth, by the heart hieroglyph ( ) . The heart also represents this god. Thoth was often called the heart of the sun god Re, and in contemporary temple inscriptions the word for heart can be written with the hieroglyphic sign of the ibis, one of the animals connected to Thoth. If the heart can be written with the ibis, the bird and thus the god it represents can be written with the heart.

) . The heart also represents this god. Thoth was often called the heart of the sun god Re, and in contemporary temple inscriptions the word for heart can be written with the hieroglyphic sign of the ibis, one of the animals connected to Thoth. If the heart can be written with the ibis, the bird and thus the god it represents can be written with the heart.

| Planets | Writings (without the star determinative) |

| Sun |  |

| Moon |  |

| Saturn |  |

| Jupiter |  |

| Mars |  |

| Venus |  |

| Mercury |

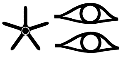

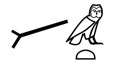

Some names of zodiac signs follow similar principles. Since the ancient astrologers often began the enumeration of the zodiac signs with Aries, it is called “the first one”, written with the Head-in-profile hieroglyph ( ) instead of “Ram”, the more common designation for the sign. Gemini could be written with two eyes (

) instead of “Ram”, the more common designation for the sign. Gemini could be written with two eyes ( ), as in the illustrated example, or with two eyebrows (

), as in the illustrated example, or with two eyebrows ( ): the two eyes recall the divine twins Shu and Tefnut, who can be referred to as the two eyes of the sun god. A third example relates to Cancer (not preserved on the ostracon). Most other horoscopes spell out the name of the sign or abbreviate it, but the present text represents it with the hieroglyph of a spine with ribs (

): the two eyes recall the divine twins Shu and Tefnut, who can be referred to as the two eyes of the sun god. A third example relates to Cancer (not preserved on the ostracon). Most other horoscopes spell out the name of the sign or abbreviate it, but the present text represents it with the hieroglyph of a spine with ribs (

![]() ). It is unclear whether the shape of the sign brought the animal to mind—the spine representing its body and the ribs its legs—or the hieroglyph indicates the body part to which the zodiac sign was connected in astrological medicine (a doctrine to be discussed in a future blog post).

). It is unclear whether the shape of the sign brought the animal to mind—the spine representing its body and the ribs its legs—or the hieroglyph indicates the body part to which the zodiac sign was connected in astrological medicine (a doctrine to be discussed in a future blog post).

| Zodiac Signs | Writing (without the star determinative) | Transcription |

| Aries | ||

| Taurus |  | |

| Gemini |   |  |

| Cancer | ||

| Leo | ||

| Virgo |  | |

| Libra | ||

| Scorpio |  |  |

| Sagittarius | ||

| Capricorn |  | |

| Aquarius |  | |

| Pisces |  |

The texts provide more than the position of the planet in relation to full signs. They also define these positions down to the degree. This allowed the astrologer to pinpoint in which terms each planet was. The terms denote a division of the zodiac signs, usually into five unequal parts. Each one belonged to a planet. The terms constitute another factor that affects the outcome of the horoscope, depending on whether a planet is in its own terms or in those of another planet.

After the position of the Moon in 20.5° Gemini (l. 4), the terms of Mars located in 18°–24° of the sign, the horoscope continues with another position: “Libra: 6°: Saturn”. What does it refer to? Although it is not explained on the ostracon, the position coincides with the last full Moon before the birth took place. This position is also related to the terms, in this case those of Saturn, which covered the first six degrees of that sign. Other horoscopes of this kind display a similar pattern. It is known that also Graeco-Roman astrologers, for instance Vettius Valens, used such points to calculate the length of the lifetime of the person for whom the horoscope was cast. Perhaps our astrologers did the same.

Although not much is preserved of the text below the section outlining the positions of the planets, it is clear that the four cardinal points (Ascendant, Descendant, Midheaven, and Lower Midheaven) are reported here and that the next section calculates some of the astrological lots. These are points on the ecliptic that were usually determined by simple principles: the astrologer measured the distance between two celestial bodies and then applied that distance from a third point. Hence exact longitudes of the planets in the zodiac signs were useful here as well. The lots also affected the predictions for a person’s fate.

Two of the most common lots in Graeco-Roman astrological literature—the Lot of Fortune and the Lot of the Daimon—are also mentioned here, along with a few other ones. Among the lots, there are four pairs. The Lot of Fortune was mirrored by the Lot of Misfortune, and the Lot of the Daimon by the Lot of the Evil Daimon, and so on. This seems to be an originally Egyptian feature, and in the names of these lots there is a striking resemblance to the terminology used for the twelve places. This underlines the development of these concepts from the same set of ideas (but that is another topic for a future blog post).

| Translation | Writing | Transcription |

| Daimon |  | |

| Evil Daimon |  | |

| Fortune |  |  |

| Misfortune |  |  |

| Life | ||

| Death |  |  |

| Flesh/Limb(s) | ||

| Illness |  |  |

In conclusion, these texts firmly refute the impression that astrologers working in the Egyptian language were satisfied with casting only simple horoscopes, while more sophisticated specimens required access to Greek.

This post has only scratched the surface of the content of these horoscopes. A fuller treatment will appear in a forthcoming paper in Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 51 (2022).

Further Readings: A. Winkler, “Stellar Scientists: The Egyptian Temple Astrologers”, Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History 8 (2021), 91–145, esp. 130–34 (click here).

[1] O. Neugebauer & R.A. Parker, “Two Egyptian Horoscopes”, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 54 (1968), pp. 231–35.