October 8, 2024, by Alessia Pilloni

“Tell me your zodiac sign (and your ascendant) and I tell you what kind of person you are.” Casting horoscopes is very popular nowadays. People of all ages and cultural backgrounds ask the stars about their character traits, about their compatibility with other people, or about how successful their career will be.

It is well established that the practice of casting horoscopes had its roots in Mesopotamia, and to be more precise – in Babylonia, at the end of 5th BC. At present, about thirty Babylonian horoscopes (Rochberg 1998) are known to us, and they were found in the cities of Babylon and Uruk, except for an unusual example found in Nippur. Babylonian astrology is a sophisticated science. It is the result of centuries of celestial divination and complex mathematical calculations that made it possible to predict the movements of celestial bodies. Horoscopes are not the only type of astrological text that the Babylonians produced, but they are the closest link to modern astrology. Were horoscopes made in the same way back then as they are made today? What has changed?

The Babylonian horoscopes are short cuneiform texts which all begin with an indication of a child’s birth date. Some of the tablets found in Uruk even record the child’s name. Next, they report the position of the planets: the Moon (sîn), the Sun (šámaš), Jupiter (MÚL.BABBAR), Venus (dil-bat), Mercury (GU4.UD), Saturn (GENNA) and Mars (AN). Their positions were calculated with sophisticated algorithms – and not observed. Astronomically calculated positions of planets at the time of birth are what in modern astrology is known as the “natal chart”. Although the Copernican Revolution taught us that the earth is not at the center of the solar system (a thousand years after Aristarchus of Samos‘ first attempt), modern astrology still does it the Babylonian way —the place of birth on earth is the point of reference, and the Sun, Moon and the other planets are located somewhere along an imaginary band, called the zodiac, which is divided into twelve equal parts, the zodiac signs. In modern popular astrology, great emphasis is given to the “personal zodiac sign,” which is the part of the zodiac where the sun was at the time of birth. For the Babylonians, the solar zodiac sign – as far as we know – did not play an important role in horoscopy. They would not, for instance, have formed a view such as “I am a Scorpio, and thus stubborn by nature.”

The rest of the information contained in the Babylonian horoscopes varies widely. Some texts from Babylon also record the moon’s passage near certain reference stars (called “normal stars” in the literature), the date of certain lunar events that occur at the beginning, middle and end of the month (“Lunar Three”), and the dates of eclipses, solstices, and equinoxes that fall closest to the date on which the child came into the world. On the other hand, some texts from Uruk indicate whether the moon was moving up or down with respect to the zodiac at the time of birth. These elements, however, are foreign to modern astrology.

So what do all these astronomical elements tell us? What is their astrological significance? The texts themselves do not give us many clues as to how these astronomical data should be interpreted. Yet there are two “astrological” terms that may point us toward a partial understanding of Babylonian horoscopy. These, always followed by the name of a planet, are:

- bīt niṣirtu, literally “house of secrecy/protection” (found in texts from Babylon);

- KI “place, location” (found in texts from Uruk).

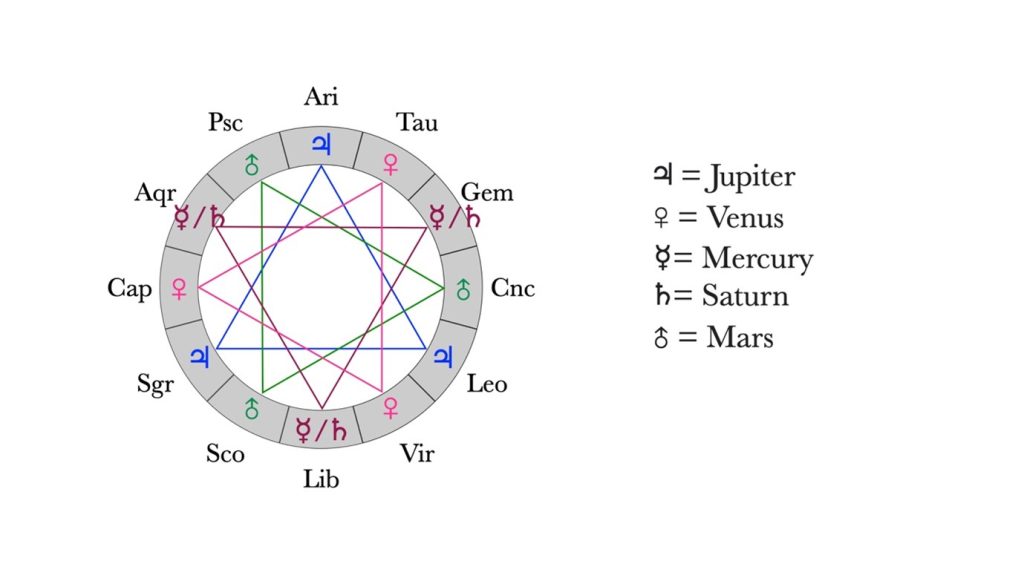

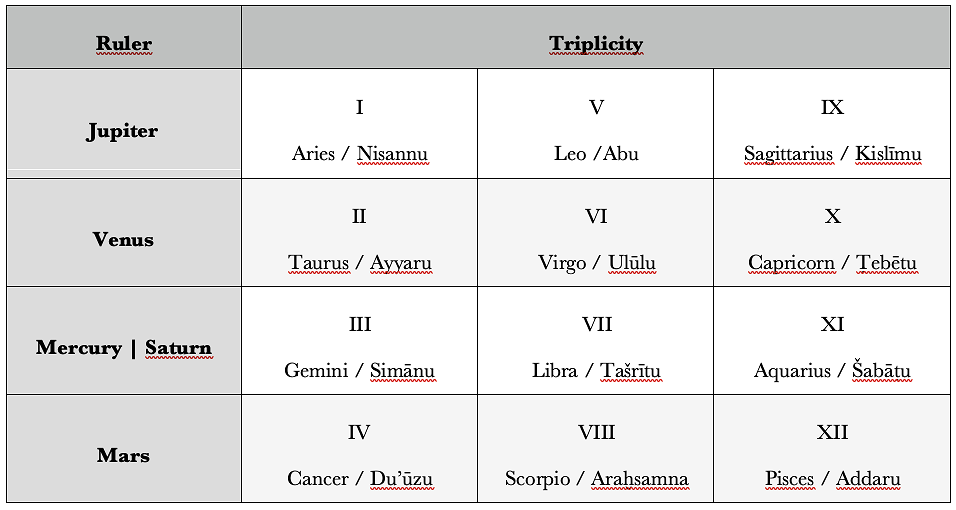

Both terms refer to a common astrological scheme —that of planetary triplicities. We have to imagine a circle divided into twelve equal parts, these being the twelve months or the twelve zodiac signs. Months and zodiac signs correspond, so the first month (nisannu) corresponds to the first zodiac sign (Aries), the second month to the second sign, and so on. In the triplicity scheme, months/zodiac signs are arranged in four groups of three, so that their distance is always four months/signs (i.e., 120°) along the zodiacal circle. Every group of three is ruled by a planet (or two, in the case of Mercury and Saturn for the third triplicity).

This scheme seems to have been creatively interpreted, and, so far, three variations of it have been identified (Pilloni 2024):

- In a group of three horoscopes from Babylon, the “house of secrecy/protection (bīt niṣirtu) is related to the triplicity of the month of the solstice or equinox that occurs the closest to the date of birth of the child. For instance, in the Babylonian Horoscope no. 8 (Rochberg 1998) we read: “That year, the 8th of Ṭebētu (Month X) was the date of the (winter) solstice”. The child is born in the “house of secrecy/protection” of Venus” (rev. 1–3). Ṭebētu (month X) is part of the triplicity of months II-VI-X, of which Venus is the ruler. Unfortunately, the significance of the child being born in the “secret house” of a planet is obscure. An important aspect to be pointed out is that this planet is the ruler of a triplicity of a month that is not the month of birth, but that of another astronomical event, namely the solstice or equinox that falls closer to the date of birth.

- In the case of a horoscope from Uruk, the “place” (KI) is related to the triplicity of the zodiacal position of the planets at the time of birth. If a planet is in a sign that belongs to the triplicity of that planet, then the child will have good fortune. For instance, in this horoscope (no. 10 in Rochberg 1998), Jupiter is in Sagittarius. Aries-Leo-Sagittarius is the triplicity ruled by Jupiter, that is why the text says “Jupiter in 18° Sagittarius. The ‘place’ of Jupiter: prosperous, at peace; his wealth will be long-lasting, long days” (obv. 6-7).

- The third case is a more complicated variation of the triplicity scheme, based on a further subdivision of the months/zodiac signs, called “terms”. The “terms” are subdivisions of each month/zodiac sign into five parts, each assigned to one of the five true planets (excluding the Sun and Moon). What does this have in common with the triplicities? According to the Babylonian scheme of “terms,” (BM 36303+, see Steele 2015), the first “terms“ of each month/zodiac sign corresponds to the planet that rules the triplicity of that month. So, for instance, the first “terms” of Aries/nisannu (=month

| I Aries / nisannu | 1–5 Jupiter 6–12 Venus 13–20 Mercury 21–25 Saturn 26–30 Mars |

- I) are dedicated to Jupiter, which is the ruler of the triplicity I-V-IX.

In a group of texts from both Uruk and Babylon, bīt niṣirtu and KI may refer to the day and month of birth. Let us see how it works step by step. The month of birth is divided into five intervals of days, called “terms,” each one assigned to a planet. The day of birth falls into one of these intervals. The bīt niṣirtu and KI are those of the planet assigned to the “terms” (interval of days) of the month of birth. An example might be helpful here. In horoscope no. 13 (Rochberg 1998), the child was born on the fourth day of the fifth month. Later the text says that the child was born in the “house of secrecy/protection” (bīt niṣirtu)of Jupiter. Days 1-5 of the fifth month are dedicated to Jupiter, and it is indeed in Jupiter’s “house of secrecy/protection” that the child was born. Possibly, depending on the planet, different predictions would be made for the child.

Horoscopic practice has changed a great deal since Hellenistic Babylonian times. The idea of calculating the position of the planets along the zodiac on the date of birth and deriving predictions for the child’s life has remained the same, but the way these predictions are derived is completely different. Astrological practices were learned, transformed and enriched in the following centuries by the Egyptians, the Greeks, and the Romans, who introduced other concepts, some of which are still in use today, such as that of the ascendant (zodiac sign rising in the east at the time of birth) and astrological houses. What about the daily horoscopes, certainly the most popular astrological practice nowadays, present on TV, in newspapers or social media? There were methods in Greek astrology to generate forecasts valid down to the day and even hour. An entire discipline of Graeco-Roman astrology, “catarchic,” is devoted to finding the right time (i.e., day and even hour) to plan activities of daily life. Juvenal (Satire 6) writes about Roman women who won’t leave the house without consulting.[1] For the “newspaper horoscopes,” we have to wait until 1937 (AD!), when the British astrologer Richard Harold Naylor starts giving general day-by-day predictions for every person born under a certain (solar) zodiac sign (Holden 2006).

Quoted literature

- Holden, J. H. (2006). A History of Horoscopic Astrology: From the Babylonian Period to the Modern Age (2nd ed.). American Federation of Astrologers.

[1] I thank Michael Zellman-Rohrer for providing me with this information on the origin of the day-by-day horoscope.