These are the major take-aways from today’s lecture.

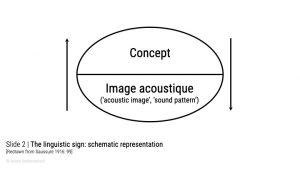

1. In spoken languages, signs are combinations of a meaning concept (a mental knowledge structure of some sort, simply referred to as concept) and a sound concept (a mental representation of a particular sequence of phonemes, referred to as an acoustic image in early structuralist linguistics, more likely referred to as a phonemic representation nowadays).

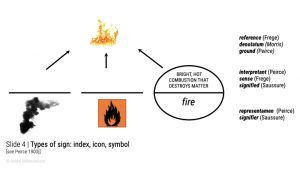

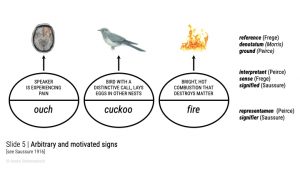

2. The link between sound and meaning is arbitrary for almost all linguistic signs, i.e., there is no reason why this particular sound should be linked to this particular meaning. Take the word fire – it refers to “combustion or burning, in which substances combine chemically with oxygen from the air and typically give out bright light, heat, and smoke” (Oxford New American Dictionary), but nothing about the sound sequence /ˈfaɪɚ/ (AmE) or /ˈfaɪə/ (BrE) has a logical connection to this meaning – speakers simply have to learn the association.

3. Such arbitrary signs are called symbols. There are two other types of sign: iconic signs, where the form resembles the meaning, and indexical signs, where the form correlates with the meaning in our experience.

4. There are a few apparent exceptions to arbitrariness in language: some words, like cuckoo, resemble (some aspect) of their meaning (in this case, the noise that the bird makes) – they are partially iconic. However, the iconicity is limited: first, we still have to learn that a cuckoo is called cuckoo, but a rooster is not called cockadoodledoo; second, the similarity is very marginal, concerning not the meaning (here: the bird) itself, but only a peripheral aspect (the noise the bird makes). Some people also argue that there are indexical signs, like the word ouch that might be an intuitive reflex of pain. Again, the indexicality is limited: first, we don’t have to say ouch when we feel pain, but there has to be smoke if there is fire; second, there is a lot of variation in different languages concerning the noise associated with pain, showing that these expressions, too, are largely arbitrary.

5. In other words: arbitrariness is a very basic and general principle of human language.

6. Signs may be simple, like fire, which does not consist of smaller signs, or complex, like fire fighter, which consists of smaller signs, fire, fight, and -er. Signs that cannot be split up into smaller signs are called morphemes.

7. Morphemes can combine into larger words and words can combine into phrases and sentences. This allows us to express an infinite number of thoughts with a limited inventory of morphemes. Interestingly, the morphemes themselves are complex on the level of sounds: they consist of one or more phonemes (typically more than one) that do not have meaning themselves. This property of language is called duality of patterning (or double articulation): on the first level, (meaningful) morphemes are combined into larger meaningful structures, on the second level, meaningless phonemes are combined into larger meaningless structures (syllables). This allows us to use a limited set of phonemes (English has between 30 and 40, depending on which variety we are talking about) to create a limitless number of morphemes (nobody knows how many morphemes English has, but several tens of thousands is a good guess).