In addition to the main take-away points from the previous post, there was a short discussion of the relation between meaning, sounds and writing.

1. Please get used to thinking about sounds and letters as completely separate elements of linguistic structure. Especially in English, it does not make sense to say that “a letter is pronounced in a particular way” or “a sound is written in a particular way”. Linguistic are units that link sound and meaning, writing is irrelevant to this link.

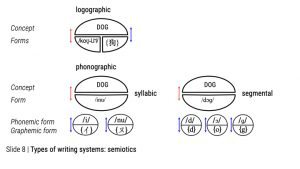

2. However, of course most speech communities use some form of writing, so it is an interesting question how written forms are related to sound an meaning. Remember the different types of writing systems we talked about in Week 1. How might they fit into a model of linguistic signs? For logographic writing systems, this is relatively easy to answer: the written form must be linked directly to the meaning side of a linguistic sign. It is related to the sound only because the sound is also related to this meaning (see Slide 8, example from Chinese). For phonographic writing systems we could imagine a separate level of “signs” where the form is a particular character and the “meaning” is a particular sound, as in the Japanese example on Slide 8 (the word [inu] is written by using the characters corresponding to the syllables [i] and [nu]).

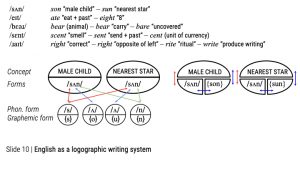

We could imagine the same for English, but this would fail because d does not always stand for [d] (it stands for [t] in walked, for example), o does not always stand for [ɔ] (it stands for [u] in boot and [oʊ] in home, for example), and g does not always stand for [ɡ] (it stands for [f] in enough). So while in “shallow” orthographies like Spanish, we may think of letters as having sounds as their “meaning”, in deep orthographies like English, the written form must be attached directly to the meaning, as in Chinese.

We could imagine the same for English, but this would fail because d does not always stand for [d] (it stands for [t] in walked, for example), o does not always stand for [ɔ] (it stands for [u] in boot and [oʊ] in home, for example), and g does not always stand for [ɡ] (it stands for [f] in enough). So while in “shallow” orthographies like Spanish, we may think of letters as having sounds as their “meaning”, in deep orthographies like English, the written form must be attached directly to the meaning, as in Chinese.