Here the presentation from session 5.

Session 6

Dear all,

For our next session:

- Watch the following videos: Morphology: Inflection and derivation; Morphology: word formation;

- Read the Plag et al. (2009): 70-108 text;

- Solve the new homework;

Have a nice week!

Magdalena

5th session

A big thank you to everyone contributing this week, I feel like we had some good discussions because of that. Looking forward to seeing you all next week!

Week 6 material

Week 6 (9 December): Text, video, & homework

Dear all,

thank you for participating in the live session of our seminar. The presentation can be found, as every week, in the folder very practically called Presentations. In preparation for the next week’s session, please do the following:

- Read the following text:

- There is no new text for next week. However, you might want to reread our last text, i.e. Bieswanger & Becker (2017: 75-95).

- Watch the following videos:

- Have a look at the sheet with your new homework tasks.

- You can find it on the Blackboard page of this seminar in the Course material/Homework folder.

- If you feel like it, fill out this feedback form.

If you have any questions, feel free to contact me at any time!

Best wishes,

Martin

[17310/17339] Reading and videos for week 6

Dear all,

The next week will be about morphology again, there is no new reading. (But some of you said they were overwhelmed by too much new terminology, so do look at the text again and use the forum to clarify any points of doubt.)

Next videos:

Morphology IV: Inflection and Derivation

Morpology V: Word Formation

There’s no new homework, either. Please go through the exercises for week 5 again and make a note of what you’d like to discuss in more detail.

We are going to begin with breakout-sessions on the homework next week. If you would like to discuss the homework in small groups, please join our live-chat punctually at 10:15 so that I can team you up. You are also free to work in the forum instead, however. In that case, join us at 10:45 as usual.

Week 6

Quicklinks:

Webex Room: weekly live seminars Mo. 16:00–18:00

Schedule: weekly readings, videos and homework

Course Bibliography

Next Videos:

Morphology IV: Inflection and Derivation

Morpology V: Word Formation

Updates

By popular request, I have uploaded the next homework. Slides are linked as well this week. Video links are following tomorrow. Don’t forget to read the weekly chapters in the book!

Bonus

Here is the link to the phonotactics video featuring Hawaiian ‘Mele Kalikimaka’. Tom Scott’s channel is also interesting and used to focus heavily on linguistics. Another guy with a linguistics degree who has turned science communicator.

Crucial follow-up reading addressing the observation about birds during the lecture: http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/sillymolecules/birds.pdf

Week 4 (Part II): Meaning, sound and writing

In addition to the main take-away points from the previous post, there was a short discussion of the relation between meaning, sounds and writing.

1. Please get used to thinking about sounds and letters as completely separate elements of linguistic structure. Especially in English, it does not make sense to say that “a letter is pronounced in a particular way” or “a sound is written in a particular way”. Linguistic are units that link sound and meaning, writing is irrelevant to this link.

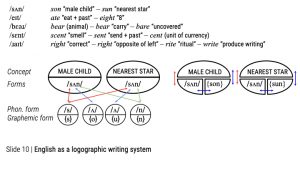

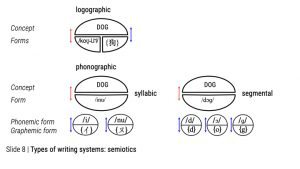

2. However, of course most speech communities use some form of writing, so it is an interesting question how written forms are related to sound an meaning. Remember the different types of writing systems we talked about in Week 1. How might they fit into a model of linguistic signs? For logographic writing systems, this is relatively easy to answer: the written form must be linked directly to the meaning side of a linguistic sign. It is related to the sound only because the sound is also related to this meaning (see Slide 8, example from Chinese). For phonographic writing systems we could imagine a separate level of “signs” where the form is a particular character and the “meaning” is a particular sound, as in the Japanese example on Slide 8 (the word [inu] is written by using the characters corresponding to the syllables [i] and [nu]).

We could imagine the same for English, but this would fail because d does not always stand for [d] (it stands for [t] in walked, for example), o does not always stand for [ɔ] (it stands for [u] in boot and [oʊ] in home, for example), and g does not always stand for [ɡ] (it stands for [f] in enough). So while in “shallow” orthographies like Spanish, we may think of letters as having sounds as their “meaning”, in deep orthographies like English, the written form must be attached directly to the meaning, as in Chinese.

We could imagine the same for English, but this would fail because d does not always stand for [d] (it stands for [t] in walked, for example), o does not always stand for [ɔ] (it stands for [u] in boot and [oʊ] in home, for example), and g does not always stand for [ɡ] (it stands for [f] in enough). So while in “shallow” orthographies like Spanish, we may think of letters as having sounds as their “meaning”, in deep orthographies like English, the written form must be attached directly to the meaning, as in Chinese.

Week 4 (Part I): The linguistic sign

These are the major take-aways from today’s lecture.

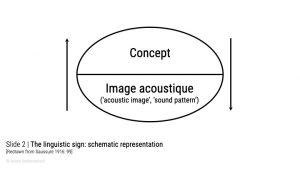

1. In spoken languages, signs are combinations of a meaning concept (a mental knowledge structure of some sort, simply referred to as concept) and a sound concept (a mental representation of a particular sequence of phonemes, referred to as an acoustic image in early structuralist linguistics, more likely referred to as a phonemic representation nowadays).

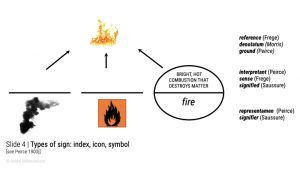

2. The link between sound and meaning is arbitrary for almost all linguistic signs, i.e., there is no reason why this particular sound should be linked to this particular meaning. Take the word fire – it refers to “combustion or burning, in which substances combine chemically with oxygen from the air and typically give out bright light, heat, and smoke” (Oxford New American Dictionary), but nothing about the sound sequence /ˈfaɪɚ/ (AmE) or /ˈfaɪə/ (BrE) has a logical connection to this meaning – speakers simply have to learn the association.

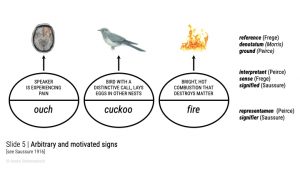

3. Such arbitrary signs are called symbols. There are two other types of sign: iconic signs, where the form resembles the meaning, and indexical signs, where the form correlates with the meaning in our experience.

4. There are a few apparent exceptions to arbitrariness in language: some words, like cuckoo, resemble (some aspect) of their meaning (in this case, the noise that the bird makes) – they are partially iconic. However, the iconicity is limited: first, we still have to learn that a cuckoo is called cuckoo, but a rooster is not called cockadoodledoo; second, the similarity is very marginal, concerning not the meaning (here: the bird) itself, but only a peripheral aspect (the noise the bird makes). Some people also argue that there are indexical signs, like the word ouch that might be an intuitive reflex of pain. Again, the indexicality is limited: first, we don’t have to say ouch when we feel pain, but there has to be smoke if there is fire; second, there is a lot of variation in different languages concerning the noise associated with pain, showing that these expressions, too, are largely arbitrary.

5. In other words: arbitrariness is a very basic and general principle of human language.

6. Signs may be simple, like fire, which does not consist of smaller signs, or complex, like fire fighter, which consists of smaller signs, fire, fight, and -er. Signs that cannot be split up into smaller signs are called morphemes.

7. Morphemes can combine into larger words and words can combine into phrases and sentences. This allows us to express an infinite number of thoughts with a limited inventory of morphemes. Interestingly, the morphemes themselves are complex on the level of sounds: they consist of one or more phonemes (typically more than one) that do not have meaning themselves. This property of language is called duality of patterning (or double articulation): on the first level, (meaningful) morphemes are combined into larger meaningful structures, on the second level, meaningless phonemes are combined into larger meaningless structures (syllables). This allows us to use a limited set of phonemes (English has between 30 and 40, depending on which variety we are talking about) to create a limitless number of morphemes (nobody knows how many morphemes English has, but several tens of thousands is a good guess).

Homework for week 5

Dear all,

In preparation for week 5:

- Please watch the following videos: (Phonology to) Morphology I, (Phonology to) Morphology II, and (Phonology to) Morphology III;

- Read Bieswanger & Becker 2017: chapter 4 (pp. 75-95);

- and do the homework.

See you next week!

Magdalena