By Jan Osenberg

Summary: Does a strong civil society lead to more moderate party preferences? This master’s thesis presents empirical evidence in support of the moderating role of civil society by examining the rise of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in a cross-regional perspective.

After a period of apparent stability, new divides articulated by populist forces have shaken the foundation of political systems across Europe. In light of this, scholars and journalists have attempted to grasp the roots of the polarization between the newly emerging, often authoritarian challenger parties and the established parties. A paradigmatic case is the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (Ruhose 2019, Schmitt 2018).

One characteristic of new challenger parties is the explicit refusal and often aggressive rejection of the established parties. Compared to populist parties, established parties are more likely to compromise and prioritize cooperation, which is beneficial for the functioning of democracy. This is why identifying factors that lead to voting for moderate parties, such as moderate party preferences, is of high interest for politics in general.

According to Alexis de Tocqueville (1840) and Robert Putnam (1994), a key factor contributing to political moderation is a strong civil society and individuals who promote civil society through a mindset called “civicness”. Not only is civic behavior believed to correlate to voting preferences, but through the so-called “rainmaker effect,” the presence of civil society organizations is also said to affect everyone in a region, even those who are not explicitly involved in civil society.

Strictly speaking, civil society consists of groups in which people create a public good, including soccer clubs, churches, and human rights organizations. In the following, the term is understood more broadly. In this way, a characteristic of civil society is that people work together cooperatively, cementing trust and cohesion. Groups in civil society are accessible to everyone, with little hierarchy among members who independently choose the extent and nature of their engagement. The space in which they operate is independent from politics, private matters, professional interests or having to sustain oneself. Therefore, citizens can develop ideas and shape public life freely, establishing a counterweight against the state and the economy (e.g. Arató 2019, Coleman 1994, Dahrendorf 1990, de Tocqueville 1840, Putnam 1994).

My master’s thesis in the program Sociology – European Societies at Freie Universität Berlin is built on these general insights. Following from them, it illustrates how a strong civil society is associated with voting preferences leaning towards established, instead of populist, parties.

In my thesis, civicness (on the individual level) and civil society (on the aggregate level) were operationalized using three variables each; the first aspect of a person’s civicness is her activity in membership organizations. Second is the strength of trust in one’s environment, and third is the amount of exposure to people with different political opinions. To create a measure for civil society, the variables were aggregated to the regional level. With the help of a multilevel regression using data from the Allbus survey (2018) it was tested whether and how these two concepts explain voting for established parties. The voting behavior was operationalized as the difference of voting probabilities between all established parties and the AfD.

When we look at the concrete mechanisms behind the moderation of party preferences, we expect that on the individual level, people in civil society organizations learn democratic habits when interacting with others. Additionally, people who trust each other are believed to be less suspicious towards the political system. Lastly, interactions between people with different opinions can teach people to withstand differences and work more cooperatively. On the local level, civil society organizations create advantages and opportunities for everybody in a certain region, even for people who are not actively engaged in them, consequently reducing mistrust against the governing, established parties (e.g., Coleman 1994, Fennema and Tille, 1999, Putnam 1994, van Deth 2000).

The results show that members of civil society organizations tend to favor established parties. Members of civil society organizations prove to be especially trustworthy, and this strongly relates to voting for established parties, pointing to the fact that mutual trust is an important foundation for cooperative behavior and solidarity among people. Additionally, having contact with those of a different background turns out to predict preference for established parties and can thus be interpreted as emphasizing the value of solidarity. Overall, the effect of a person’s civicness is about as strong as the effect of education.

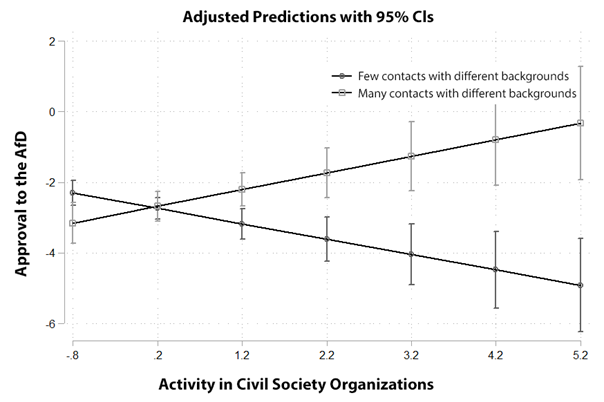

Alexis de Tocqueville predicted that civil society organizations will have a moderating effect, because members learn the art of compromise and cooperation. However, the results suggest otherwise. As the following figure demonstrates, contact with people with different backgrounds tends to increase engagement in populist parties if the respective person is integrated into civil society organizations. In these cases, the results suggest that organizations do not teach the art of compromise but instead foster arguments for populist parties, such as ingroup-outgroup thinking. Civil society organizations only have a moderating effect on people with few relations to outsiders.

Figure: The impact of civil society and contacts with different backgrounds on the approval for the AfD.

Lastly, the results point to the fact that party preference polarization is stronger in regions with relatively few civil society organizations. It is likely that the actions of civil society, such as organizing a village fairly or constructing a playground mitigate anger which is otherwise directed at politicians. Additionally, civil society organizations act as mediators who facilitate the communication between citizens and politicians, and vice versa. This effect partly explains the polarization towards the AfD in Eastern Germany, which belonged to the German Democratic Republic until 30 years ago. There, civil society was strictly suppressed.

From this analysis we can conclude that an important influence on voting behavior and thus, political stability, has been neglected in recent years; civil society. The statistical calculations show that not only personal attributes such as gender, education, or professional matters such as income and class, are relevant to political behavior. Instead, activities and modes of cooperation outside of jobs as well as the private sphere should be looked at more closely. It remains up to further research to specify the mechanisms behind the effect of civil society.

This finding should be kept in mind when looking at strongly polarized party systems such as the one in America or the polarization between conspiracy theorists and the mainstream during the course of the Covid-19 pandemic. Similar to the AfD, the German “Querdenker” movement propagates a strong critique of the government often, relying on irrational reasoning and black-and-white thinking. Based on the above calculations, a strong civil society is a tool to mitigate such developments.

Literature:

Arató, K. (2019). Civil Society: Today: Democracy and Civil Society in Europe. Presentiaton at the Dahrendorf Conference, December 4, 2019, WZB Berlin. Available at https://vimeo.com/showcase/6326401/video/379714357

Coleman, J. S. (1994). Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Dahrendorf, R. (1990). Reflections on the Revolution in Europe. London: Routledge.

de Tocqueville, A. (1840). Über die Demokratie in Amerika, Stuttgart: Reclam.

Fennema, M. & Tillie, J. (1999). Political participation and political trust in Amsterdam: Civic communities and ethnic networks. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 25(4): 703-726.

GESIS – Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften (n.d.). Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften ALLBUS 2018.

Putnam, R. D. (1994). Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ruhose, F. (2019). Die AfD im Deutschen Bundestag: Zum Umgang mit einem neuen politischen Akteur. Wiesbanden: Springer.

Schmitt, J. (2018). Zur Wirkung einer Großen Koalition: Die Renaissance des polarisierten Pluralismus und die Polarisierung des deutschen Parteiensystems. MIP Zeitschrift für Parteienwissenschaften 24(1): 48-63.

van Deth, J. W. (2000). Interesting but irrelevant: Social capital and the saliency of politics in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research 37(2): 115-147