By Zozan Baran

Summary: How and why have challenger-AKP government interactions changed over time and across different policy areas? Adopting a contentious politics perspective and based on original content analysis, this master’s thesis sheds new light on the controversial debate about the Turkish AKP’s transformation.

Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) presents a puzzling case. The AKP rule is now widely recognized as dictatorial, yet was initially praised by various actors as a shift to a democratic ruling by a former Islamist party. However, this praise mostly focused on a strictly institutional understanding of what democracy was, as opposed to democracy as a bottom-up process. Thus, such assessments did not pay much attention to the empirical reality of AKP’s interaction with society. Instead, they were widely based on AKP’s institutional performance and the historical analysis of the “center-periphery” cleavage. From the latter perspective, AKP was a democratizing force as the representative of those who remained at the periphery of the state-led modernization processes, or effectively, the modern political system.

Based on original empirical data, my master’s thesis in the program “Sociology-European Societies” reevaluates party-society relations in the Turkish case and asks: “How and why have challenger-AKP government interactions changed over time and across different policy areas?” The results highlight the evolution of AKP’s rule over time and the strategies that the party used in forming alliances or silencing critics from civil society and beyond.

AKP started its political breakthrough in 2002 as a liberal-conservative split from the Islamic tradition. Before it came to power, its prominent figures sung praises for the European Union and expressed enthusiasm for a reform program for EU candidacy. These warm messages towards the EU in particular and Western countries in general were promoted by further actions once the party was in power (Insel, 2003; Keyman & Gumuscu, 2014). Widely deemed a democratization process, it contained reform actions in favor of religious and ethnic minorities, fracturing the dominance of the military over the country’s political system, and above all intensifying the neoliberal transformation of the economic system in a pro-Western fashion that was unexpected from an Islamist political party. To understand the gravity of this political shift, it may suffice to remind the readers that a deeper integration with the EU and the neoliberal international order was proposed (Akça 2014) by the military to stop the Islamists’ ascendance to power at the end of 1990s.

Such reforms led many left-liberal intellectuals to see a democratic energy in the AKP rule, a typical example of which came in 2003 from Ahmet Insel, a renowned intellectual of left-liberal circles in Turkey (see Insel, 2003). In praising the AKP, these intellectuals exclusively interpreted the party’s actions through the lens of the cleavage structure widely known among the scholars of Turkey as center-periphery dichotomy in state-civil society relations. According to this reading of the modernization process of the Ottoman Empire and the foundation of the Turkish Republic, the Turkish political system is based on a cleavage between an authoritarian center (or the state) and the periphery onto which the center imposes its modernizing agenda in a top-down fashion (see Heper, 2000; Mardin, 2006). Resistant to this top-down process, the periphery happens to represent more democratic tendencies and comprises masses that are culturally religious and conservative. According to this account, the AKP that represents this part of society is now embarking on a historical task to correct the wrongdoings of the secular elites and the founders of the Republic.

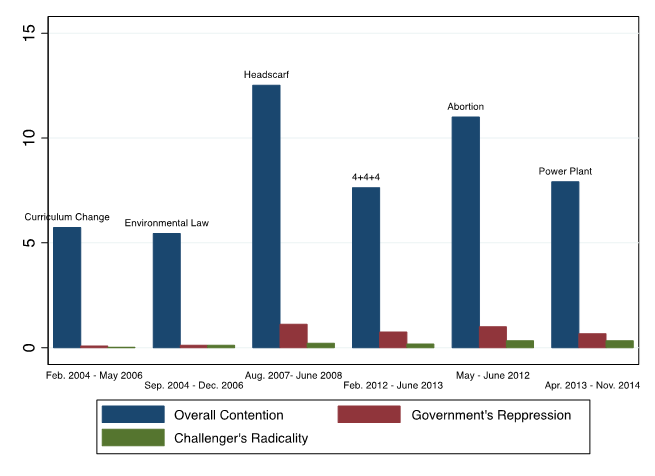

Drawing on the Contentious Politics approach (McAdam et al., 2001) and the toolkit provided by Contentious Episode Analysis (CEA) (Bojar et al., forthcoming), I examined AKP-challengers-third party interactions in six episodes around environmental, gender and education policy reforms. The analysis combined a quantitative coding of Cumhuriyet newspaper’s archive with qualtitative process-tracing. To explore the variation over time, two episodes from each policy area were chosen, one from AKP´s first years in power, when the party was considered liberal, and one from the 2010s, when the oppressive tendencies became more dominant.

Graph 1: Contentiousness per Episode

In my analysis, two results were especially striking and call for a qualification of the historical and political positions mentioned above, if not their complete revision.

First, no positive interaction and concessions for the challengers are detected in the first years. As shown above in the figure, the contentiousness has increased over time. Yet the episodes from the first period (i.e., the first three episodes in Graph 1) did not show any evidence in support of a more democratic tendency during the first years of the AKP rule. The low level of contentiousness in the first two episodes stemmed from the lack of any meaningful interaction (hence, low number of actions coded). Instead of recognizing the challengers’ demands, the AKP government did not engage at all. Following Dina Bishara’s conceptualization of “ignoring” as “absence of repression and meaningful concession,” we can conclude that what the first two episodes show is the government ignoring its challengers and their demands. This is most likely caused by the institutional character of the challengers in these first episodes. Instead of highly institutionalized actors such as political parties or republican NGOs, the actors in these episodes were far less institutionalized, ranging from environmentalist, left-leaning unions to parent initiatives. Therefore, contrary to what the perspective on AKP as a democratizing force in center-periphery relations leads us to expect, my findings reveal that the party ignored actors that are at the confines of the political system.

The headscarf episode, which started in 2007 following discussions over the AKP presidential candidate’s wife wearing a headscarf, represents a turning point as by far the most contentious episode. Despite the pressure from civil society, the government refused to make concessions to its challengers. In fact, the contentiousness in this episode was partly driven by the government itself (see high repression in Graph 1), which employed both legal actions, such as law changing in the desired direction and institutional actions, such as changing the composition of the Constitutional Court.

Second, I found no support for the theoretical and political analysis which situates democratic tendencies in the periphery – when periphery is understood as the conservative parties and their constituents. On the contrary, far from being excluded from the bureaucratic institutions, the religious conservatives were able to mobilize institutional means in their support. For example, the judiciary and other institutions did not challenge reform actions by the AKP government in education and environmental policies in the first period. Yet, YÖK and partially the Constitutional Court (or its members) gave voice to the changes desired by the AKP in the headscarf episode. Therefore, the claim that the center (or the state) being exclusively at the hand of secular elites and alien to conservatives tends to not stand up to close scrutiny.

The exclusively cleavage-structure centered reading that is asserted by the left-liberal and conservative intellectuals also seems to ignore the dialogue and cooperation that come from both sides in support of the other. While many civil society actors (such as then friend, now foe Gülen community) mobilized in support of the government with the help of legal and institutional actions, the secularists had their backing from other segments of the civil society (republican NGOs, unions, professional chambers) and could mostly voice the same demands with different, yet complementary actions. This reflects the complex and intermingling structure of what we refer to as civil society. It comprises of various groups and people that are favored or oppressed by different political actors in power. For example, the subaltern voices such as feminists, environmentalists, unions, and students are widely ignored by both seculars and religious conservatives.

In conclusion, my master’s thesis highlights that by investigating challenger-government interactions, the quality and nature of the AKP’s democratic capacity can be understood in a different light. The AKP-challenger interaction grew increasingly contentious starting with the headscarf episode. However, it did not shift from a cooperative one to a conflictual one, rather from non-existent to an increasingly oppressive dynamic with many institutional and non-institutional as well as central and peripheral actors involved on both sides of the conflict.

Literature:

Akça, I. (2014). Hegemonic Projects in Post-1980 Turkey and the Changing Forms of Authoritarianism. In A. Bekmen, B. A. Özden, & I. Akça (Eds.), Turkey Reframed (pp. 13–46). Pluto Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183p72x

Bishara, D. (2015). The Politics of Ignoring: Protest Dynamics in Late Mubarak Egypt. Perspectives on Politics, 13(4), 958–975. https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759271500225X

Bojar, A., Gessler, T., Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (Eds.). (forthcoming). Contentious Episodes in the Age of Austerity: Studying the Dynamics of Government-Challenger Interactions. Cambridge University Press.

Heper, M. (2000). The Ottoman Legacy and Turkish Politics. Journal of International Affairs, 54(1), 63–82. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24357689

Insel, A. (2003). The AKP and Normalizing Democracy in Turkey. The South Atlantic Quarterly, 102(2), 293–308.

Keyman, E. F., & Gumuscu, S. (2014). Democracy, Identity, and Foreign Policy in Turkey. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137277121

Mardin, Ş. (2006). Religion, society, and modernity in Turkey (1st ed). Syracuse University Press.

McAdam, D., Tarrow, S. G., & Tilly, C. (2001). Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge University Press.