By: Cordula Dittmer and Daniel F. Lorenz

Original version in German published: May 28, 2024

Translated version published: August 20, 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/refubium-45267

On April 23, 2024, as part of the Disaster Preparedness Conference, a session organized by Dr. Daniel F. Lorenz and Dr. Cordula Dittmer was held on emergency aid in Ukraine, particularly discussing what lessons can be learned from these experiences for the context of German civil protection. In this session, four different specialized presentations were given by Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH), Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe (JUH), Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund (ASB), and the Disaster Research Unit (DRU; German: KFS), which presented specific emergency relief measures in Ukraine and discussed various aspects of possible lessons for Germany.

The following objectives were associated with the session:

- Discussion of Humanitarian Aid under War Conditions: Many humanitarian organizations, development cooperation organizations, and civil protection organizations were already active in Ukraine to some extent before the unlawful annexation of Crimea in 2014, while others joined after 2014 or have been involved since 2022. The escalation of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, which has now lasted for over two years, has begun to get less attention amongst the general public, as well as professional circles. Bringing humanitarian aid, currently operating in Ukraine under wartime conditions, back into the discussion was a central concern of the session.

- Opportunities and Limits of Humanitarian Aid in Areas where International Humanitarian Law is Ignored: This raises new questions and challenges for humanitarian actors about how humanitarian aid is possible in contexts where humanitarian principles (especially neutrality and independence) are difficult to maintain, such is in Ukraine. Additionally, the international humanitarian law, which should protect aid workers, is not respected by Russia in practice or is even deliberately counteracted as part of warfare.

- Contribution to the Discussion of Civil Protection in Germany: This war also leads to a re-evaluation of previously held beliefs in Germany: the question of how well-prepared Germany would be for a wartime scenario, which had been little discussed until now, is now being significantly more publicly debated, including in the civilian sector. While there were civil protection plans during the Cold War, it is currently questionable how well these can be adapted to today’s times and society. Learning from international experiences might provide much broader insights. Various topics that could be addressed include medical care for individuals with war-related injuries or under war conditions, evacuation of elderly and vulnerable persons, operation of “civil protection beacons” under extreme conditions, and warning systems. These topics, among others, were addressed in the presentations.

- Establishment and Expansion of Social Science Research on Civil Protection: This includes, firstly, stimulating a scientific debate on civil protection by incorporating insights from social and political sciences, peace and conflict studies, and disaster research, to establish this field in the first place. This seems particularly challenging for the German context in light of the crimes of the National Socialists and national experiences during World War II, as these are inscribed differently in the collective memory compared to other European member states. Secondly, we understand civil protection from a social science perspective as a “social question” (Clausen 1994) particularly as civil protection also encompasses the establishment of social practices. This means we assume that civil protection is not only exhausted in state structures and plans, but that various social, often informal, practices develop within the population in response to certain situations, complementing the formal structures of civil protection. As such, such informal, social practices can become everyday routines under ongoing war conditions – and should also be the subject of social science civil protection research. Thirdly, we perceive war as the complex disaster par excellence because, from a disaster sociology perspective (Clausen 1994) – despite all the differences in political processes – both disasters and war represent forms of “severe social change” that can only be understood in their effects through a “catastrophic form of social interweaving” (Clausen 1994: 15).

The four presentations in the session highlighted, from the perspective of various humanitarian aid organizations as well as social science disaster research, the experiences gained from emergency aid in Ukraine and the potential and challenges for learning from Ukraine for German civil protection.

- Multisectoral Support Initiated by Local Partners

Mario Göb (Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH))

Since February 2022, Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH) has seen a massive increase in donations for aid efforts in Ukraine, which have been implemented in various projects both within Ukraine and in neighboring countries such as Moldova, Poland, Slovakia, and Romania. Immediately after the escalation of the conflict, the focus was primarily on organizing aid deliveries, cash assistance programs, and providing winter relief. A current focus of DKH’s work is on repairing destroyed homes near the contact line, where many elderly people, often with disabilities, still live. These individuals are often unwilling or unable to leave their homes. Elderly people represent a disproportionately high share of civilian casualties in the war in Ukraine. Where logistically feasible and if the people are willing, efforts are made to evacuate these highly vulnerable individuals and place them in newly established and renovated care homes. However, this is extremely challenging, as many of those affected fear the unfamiliar and have few networks or contacts outside their usual social environment. Additionally, humanitarian mine clearance programs are being implemented, particularly through training sessions that educate people about the risks of landmines and unexploded ordnance and explosives.

Lessons for German Civil Protection

Prioritizing Population Protection: The protection of the population must be the top priority in emergency situations, with special consideration for highly vulnerable individuals. Cross-agency coordination and collaboration must function effectively, with clear protocols for communication and coordination in crisis situations. Flexibility and innovation are crucial for effectiveness and efficiency in these war-related situations, necessitating adaptive planning approaches.

- Cross-Agency Collaboration and Flexible Structures for MedEvac Patients

Stefan Mönnich (Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe (JUH))

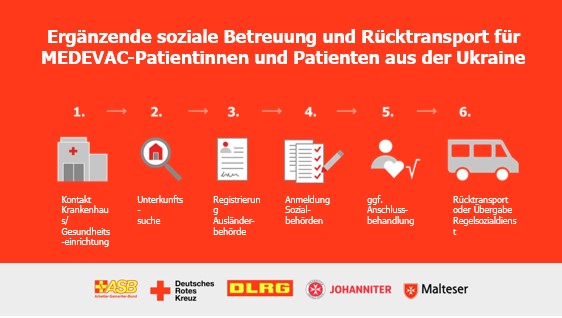

The Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe (JUH) is also involved in supporting refugees from Ukraine in Germany and assists partner organizations in Ukraine by providing food to internally displaced persons and people in villages near the frontlines, repairing roofs and windows, and restoring water pipelines. Another focus is on providing psychosocial support, particularly for women. In the context of a MEDEVAC mission under the European Civil Protection Mechanism, aimed at evacuating severely injured and ill persons from Ukraine to European countries, JUH, along with ASB, DLRG, DRK, and MHD, supports patients who are evacuated to Germany and then distributed to hospitals through the Kleeblatt system.

The aid organizations provide additional social support for the patients, particularly in dealing with official matters. They also organize medical repatriation to Ukraine for patients in need of assistance, upon their request. The project is funded by the European Union’s Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund.

Key Challenges in the Project:

- Status of the Target Group: The residency, immigration, and social legal regulations for MEDEVAC patients and their families are aligned with those for refugees from Ukraine. The administrative requirements, housing situation, or delays in treatment can be difficult for patients to understand, as they may not be seeking protection or permanent residence in Germany, but are in the country only temporarily for medical treatment.

- Data Protection: Ensuring data privacy in communication with various actors requires the establishment and practice of effective processes and secure transmission methods, both within Germany and in international communication channels.

- Lack of Psychosocial Support: Many members of the target group are traumatized by the war and urgently need psychosocial support. Given the already very limited resources in Germany, it is challenging to provide this necessary care.

- Funding: The external funding of the project offers little flexibility for necessary adjustments to address spontaneous or changing needs, making it difficult to establish sustainable and resilient structures and resources that can be reactivated in times of crisis.

Lessons for German Civil Protection

The Kleeblatt system has proven to be highly effective in practice. Since the summer of 2022, approximately 1,100 patients have received treatement in Germany. A crucial aspect of the overall process is the close cross-sectoral and inter-regional collaboration among all involved actors— that extends beyond just the Kleeblatt centers and receiving hospitals. This includes the supporting structures in municipalities, aid organizations, volunteers, and diaspora organizations. Additionally, strong networking with Ukrainian actors—such as the Ukrainian Ministry of Health and emergency services—ensures the best possible care for the patients. Competition has no place in civil protection.

Despite the professionalism of both state and non-state actors, it is essential to focus on the needs of the target groups. They require simple, understandable regulations, barrier-free access to information and feedback options in plain language, translation services, as well as low-threshold counseling and support services. The advantages of digitalization, such as was seen in Ukraine through the organization of digitally-based psychosocial support through specialists, should definitely be utilized in this context.

- “Points of Invincibility” – Civil Care Centers in Wartime

Stina Steingraeber/Michael Schnatz (Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund (ASB))

The war and displacement caused by the Russian military offensive have had a massive impact on the security of supplies throughout Ukraine. In the event of power outages or prolonged blackouts due to attacks on energy infrastructure, stationary and mobile warming centers—referred to as “Points of Invincibility” in Ukraine—provide critical support. The goal of these care centers, operated by local partner, the Ukrainian Samaritan Association, is to assist the war-affected population in and around Kyiv. As the capital city, Kyiv is a constant target for Russian airstrikes. Since the fall of 2022, critical infrastructures, especially those related to energy, have been regularly and heavily attacked. Civilian targets, such as apartment buildings, are also frequently hit or damaged by falling drone debris.

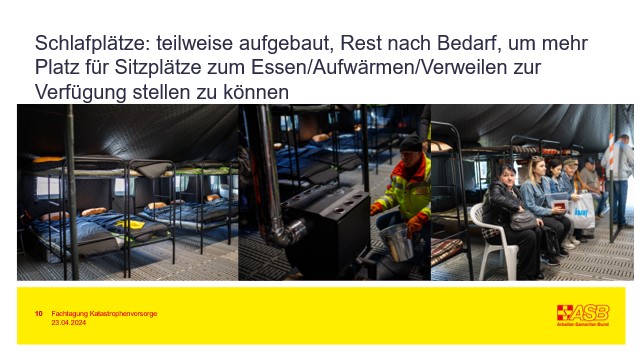

In cooperation with the city’s disaster management services, the ASB facilitates the operation of stationary warming centers equipped with tents, beds, stoves, mobile kitchens, and power supplies. These centers provide the war-affected population with warm meals and drinks, a place to warm up, and electricity to charge phones, batteries, and other essential devices.

Translation of this slide: Beds: partly already built, the rest if needed, in order to have more space for sitting areas for eating/warming up/spending time

These care centers also offer overnight accommodations (particularly after attacks or due to cold weather), as well as basic medical and psychosocial care. Play areas are provided for children. Additionally, these centers serve as distribution points for aid supplies to the war-affected population, including food, hygiene products, and winter non-food items (NFIs). There are both stationary centers and mobile units. The coordination of these care points is managed by Kyiv’s disaster management services, which have also set up their own warming points throughout the city. The coordination ensures a logical and widespread distribution of care centers across the city, making sure they are easily accessible, connected to the power grid, and located near bomb shelters.

Information about official warming centers is available online, as well as through the official Kyiv city app and the Diia app, which is widely used across Ukraine.

While these warming centers have only been operational during the winter so far, plans are in place to maintain them in the summer and expand them into year-round care points, anticipating further escalation of attacks during the summer months.

Lessons for German Civil Protection

Warnings, including specific instructions for action, are primarily issued in Ukraine via apps; although sirens are also used as alarm signals. Through the apps, there is also an option for the population to report sightings of drone attacks. Facilities to charge mobile phones are widely available. The power, mobile, and internet networks have become so self-sufficient that while large-scale power outages do occur, mobile networks are rarely immediately affected. Communication is thus always possible. The population must be taken seriously and should not be treated as “dumb.” In Ukraine, a strong national pride continues to be a unifying narrative, helping to cope with the situation. (Gallows) humor is also widespread and is shown to strengthen resilience.

- Lessons for German Civil Protection – Health Protection Example

Nicolas Bock (Katastrophenforschungsstelle (KFS))

The unlawful Russian war of aggression against Ukraine raises profound questions for German civil protection. Since the end of the Cold War, Germany has systematically reduced and dismantled components of its civil defense infrastructure. This is particularly evident in the healthcare sector, where auxiliary hospitals, the training of auxiliary nursing staff, and large parts of medical supply stockpiles were eliminated by the early 2000s. The scenario of national and alliance defense gradually disappeared as a basis for civil protection planning and was largely replaced by civilian disaster scenarios. As a result, threat scenarios were often only considered as peacetime, regionally and temporally limited incidents.

While the impacts of the war in Ukraine cannot be directly applied to Germany, the disruptions, threats, and systemic interactions in critical service systems like healthcare, as observed in Ukraine, should nevertheless be critically reflected upon in German civil protection. Given the absence of a concrete national and alliance defense scenario—and corresponding implications for the civilian side, which could serve as a basis for planning self-protection and enhancing the resilience of operational processes in sectors such as healthcare—examining the situation in Ukraine is urgently necessary.

An analysis of the healthcare situation in Ukraine, and an abstracted application to the German context, reveals that all components of the healthcare system can be perceived as targets and could potentially be attacked. The international legal protection of health facilities is no longer recognized by all states. Accordingly, in a scenario of national and alliance defense, it must be assumed that attacks on the healthcare sector in Germany, whether through drones, sabotage, or cyber operations, are to be expected and should be prepared for. The healthcare system in Germany is particularly dependent on the functionality of other critical infrastructure systems, such as energy and water supply. Attacks on these targets would therefore also affect healthcare facilities.

In Germany, few healthcare actors have taken precautionary measures for such scenarios so far. For example, hospitals generally only have limited emergency power supplies. The situation in Ukraine demonstrates that people with chronic illnesses and other vulnerable populations, often with multiple health conditions, rely on a functioning outpatient medical care system, as hospitals are frequently overwhelmed by large numbers of severely injured soldiers. However, in Germany, the military medical evacuation chains of the Bundeswehr and allied forces terminate within the civilian healthcare system.

Lessons for German Civil Protection

Translation of slide:

Possible Implications in a Defense Scenario for Germany

- Large number of injured

- System dependencies have negative results

- Individual system components are overwhelmed

- Those with chronic illness may not receive adequate treatement

- Supply chains are interrupted

- (Even bigger) shortage of available staff

- Mass migration/flight to EU/NATO countries

- Support for the host nation

The concept of a defense scenario can be understood as a resource scarcity situation, in which the adversary has a fundamental interest in overwhelming systems. This underscores the necessity for an equivalent structure that creates overall system redundancy (civil protection) to compensate for potential failures. It is increasingly crucial for all healthcare actors (not just hospitals) to develop a certain level of resilience and endurance in response to possible implications of defense scenarios. This is not only vital for national defense but also benefits peacetime disaster situations. The healthcare system’s ability to adapt is particularly necessary because civil protection measures can only provide limited, localized interventions over time and space—a comprehensive, nationwide redundancy effect was deemed practically unfeasible already as early as the beginning of the Cold War.

To address this, it is essential to broadly communicate the implications and consequences of a national and alliance defense scenario to relevant stakeholders. The situation in Ukraine further demonstrates that scenarios of defense and civilian disaster situations can no longer be sharply distinguished. For example, the war in Ukraine has thus far involved threats such as accidents at or attacks on nuclear facilities, the impact of flooding following the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, power outages, heating supply failures, and daily mass casualty incidents. While each of these scenarios in Germany is supported by contingency plans, and there are limited resources and personnel available for crisis management, the overlap and simultaneity of such situations, as observed in Ukraine, are rarely anticipated or pre-planned.

This reality necessitates a critical re-evaluation and potential adaptation of Germany’s civil protection structures. The country’s civil protection framework must be prepared to handle multiple, concurrent crises that could strain or exceed existing capabilities, drawing lessons from the complex and overlapping disaster scenarios experienced in Ukraine.