By: Cordula Dittmer and Daniel F. Lorenz

Original German version published on June 13, 2023

Translated version published July 30, 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/refubium-45261

Exactly 10 years ago, on June 10th, during the Elbe River Flood of 2013, a dike in Fischbeck broke, resulting in the flooding of a large portion of the Elbe-Havel-Land municipality. This region, overwhelmingly rural and sparsely populated, is located east of the Elbe River within the district of Stendal in the federal state of Saxony-Anhalt. Even though some areas were completely cut off from the outside world, many residents resisted the government-mandated evacuation orders in order to save their belongings, and, instead, organized themselves autonomously (Dittmer et al. 2016; Schmersal/Voss 2018). In some areas, it took up to 2 weeks for external assistance from disaster management organizations to reach the population. Disaster management assistance came from the Technische Hilfwerk (THW), the German Red Cross, the Johanniter (JUH) and the German Federal Defense Forces (Bundeswehr). The population that followed the evacuation orders and sought refuge in private accommodations and/or emergency shelters in the surrounding areas of Stendal, Jerichow and Havelberg returned to the area weeks later, some finding their homes barely habitable.

The Disaster Research Unit (KFS) conducted a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative field study in the affected municipality from 2015 to 2018 as part of the INVOLVE project. The study included conducting interviews with experts and those directly affected, stakeholder workshops, group discussions, as well as a quantitative survey of the population. The primary goal was to understand the needs and self-help capacities of the community during and after the flood in order to improve future capacities to overcome similar situations, such as those witnessed in the Ahr Valley in 2021. The findings from these research efforts were presented to the public through exhibitions in Genthin, Schönhausen and Burg, and contributed to a broader awareness and preparedness in the region.

Looking back

Disasters are not finite events isolated in time; not only are they connected to past and future conditions, but they also impact diverse present realities. Illustrating simultaneous and non-simultaneous conditions of disasters is a fundamental approach of social scientific disaster research and, therefore, also of the Disaster Research Unit.

When we began our work in the Elbe-Havel-Land municipality in 2015, we had no inkling of the breadth this endeavour would reach. However, it became clear relatively quickly- already after initial discussions with experts that were often also personally affected- that, despite appearances, the population of this region was still feeling significant after-effects of the 2013 flood events. The population was invited to a workshop to discuss this topic, of which we expected only about 7-10 participants; however, due to the immense relevance of this topic, ultimately 25 residents felt urged to participate, forcing us to overhaul our carefully crafted workshop concept. The desire and need to share experiences and find explanations was overwhelming.

In our subsequent discussions and interviews, a diverse variety of topics were prevalent, including: controversy surrounding the dike, evacuation, survival, as well as return and reconstruction. The most impactful narratives were those of the “Robinsonade”: when flood water stood for up to 14 days, turning the region into what emulated a bathtub. In one interview, this period is described as follows:

“The streets were full of cars and Bundeswehr (German Federal Defense Forces), sirens were blaring everywhere, everything was dark and hectic; I thought war was breaking out. A neighbor came and shouted, ‘We need to hide in the forest, we’re being forcibly evacuated!’ And when the people were gone, it was so beautifully quiet. Like Robinson alone on the island. About 200-300 people stayed here, mostly farmers who had to care for their animals. A local Elbe fisherman conducted a shuttle service connecting the island areas with the mainland. The weather was nice, so we fired up the grill, raided our freezers, and had roast goose and salmon from Norway. You revert to simple, primitive things; an ‘Ossi’ (East German) always knew how to help him/herself. It was a terrible beautiful time, terrible because you knew when the water recedes, it will become even more terrible, but having a moment of calm in the hectic society…” (translation from German original)

In June 2016 we collected data with the help of university students, going door-to-door with a questionnaire. Since our stay in the region was extensively covered in the local newspaper Volksstimme, we were eagerly anticipated at some doors: “I was hoping you would come!”

However, at other doors we were turned away with the explanation that they were not yet ready to discuss the topic or, alternatively, wanted to finally put the topic behind them. Having previously conducted research on various flood, flash flood and tsunami events with tens of thousands of causalities in India, Japan, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia, the suffering and enduring impact felt by many in this area surprised us- especially considering the proximity to our research center in Berlin.

We also heard numerous stories of widespread willingness to help, positive learning experiences and solidarity amongst the population, facilitating the formation of ‘emergency communities” during this challenging situation. We learned that “disaster” is highly subjective: while for one person it may have been the dismantling of the old disaster management system due to the end of the GDR, for another it may have been the seeming endless struggle with insurance companies unwilling to pay. Over the past years we’ve also come to understand that learning from the past and implementing these lessons in the future is not always as straightforward as it may seem. Who, when, how and what is learned from an event is also highly specific to the exact situation and the context that surrounds it.

To conclude this project, we designed an exhibition titled “What remains? Local and Scientific Perspectives on the Flood in the Elbe-Havel-Land” (Was(ser) bleibt? Lokale und wissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf die Flut im Elbe-Havel-Land”). The exhibition was launched on the 5th anniversary of the dike breach at the county museum in Genthin and was subsequently also displayed at the Bismarckmuseum of Schönhausen and the county college in Burg.

Parallels and Special Features

Distinct disaster events can only be compared to a certain extent; however, this endeavour can still be worthwhile as it permits us to broaden our perspectives, identify similarities and patterns, as well as, recognize differences in social behaviors and reactions in response to the disaster.

In July 2021, extreme rainfall followed by floods hit North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate, resulting in 189 deaths and over a billion in damages. Although the dynamics of the events in 2013 and 2021 were quite different- the lead time of the 2013 Elbe River flood being significantly longer than that of the extreme precipitation events of 2021- the social processes that occurred did not differ all too much. Our research within the HoWas21 project on the 2021 events shows that, for the Elbe-Havel-Land community with the dike breach, the situation rapidly accelerated over a short period of time and, although it had always been an abstract possibility, the breach and subsequent flood disaster came suddenly for many.

While the unique dynamics of the Ahr region catastrophe- including the wide spread of warning apps- raised various questions about the warning systems as well as responsibilities within the warning process, warnings played a smaller role in the 2013 flood.

Nonetheless, many aspects unite the two events. For example, parallels can be drawn between the protective dike in Fischbeck that could not withstand the desperate efforts, and the sandbags, protective measures, and gauge stations that could not contain the waters of the Ahr and its tributaries. While some places were already submerged, others still attempted last-minute preparations for the approaching flood, able to do nothing but wait—or endure the night on rooftops.

As the communities prepared for the coming disasters, both in 2013 and 2021, many questioned whether it was better to stay or evacuate. Despite a high number of casualties in 2021, many of those who stayed survived, and lived as “island residents” in the extensively flooded areas. They developed local processes and structures to cope with the situation, using their own resources until- but also still after- external help arrived.

The willingness of others to lend support in the weeks following these disasters were similar in both communities. There was widespread assistance provided to those who evacuated to emergency shelters and others who remained in the disaster-stricken areas. Help was also offered through filling sandbags, addressing damages, and/or providing donations.

All disasters evoke fundamental questions for those affected, including ones related to: causation, blame, and sometimes “scapegoats” (Drabek & Quarantelli 1967) – often also beyond rational or scientific causality (Clausen 2003). While blame in the Elbe-Havel-Land region was mostly directed at governmental authorities, in the aftermath of the 2021 flood, criticisms were also aimed at disaster management forces of the county and/or state level, as they were accused of ineffective leadership and communication deficits. The events of 2021 are still being investigated by commissions and committees, as well as undergoing legal processes. In contrast, the 2013 catastrophe, due to clearer causation and coping circumstances, did not lead to similar proceedings. Despite – or maybe inspite – this result, some affected individuals still feel that the need for more intensive investigation and examination of culpability remains.

In the Elbe-Havel-Land area, official reconstruction efforts are likely to be completed soon- in the 10th year after the catastrophe- while in the heavily affected Ahr Valley in 2021, reconstruction has only just begun. Our research on Fischbeck shows that while the years of reconstruction were able to rectify many material damages, they also highlighted the existence of various psychological and intangible long-term damages.

The social consequences in Fischbeck were described in a 2016 interview as follows:

“Sure, you won’t find houses as newly and beautifully renovated as in the flooded streets. When you ask the people who now live in these renovated houses, it often turns out that this hasn’t made them happy either. A dominant feeling seems to be, ‘we had everything, and it was our own, and now we have all this gifted stuff here.’ Thus, the new conditions of the houses don’t make people as happy as one might assume. Also, then a lot of envy and resentment arose: ‘I got too little. Why did he get all that?’ Nerves were clearly frayed. Some interpersonal relationships were ruined.”

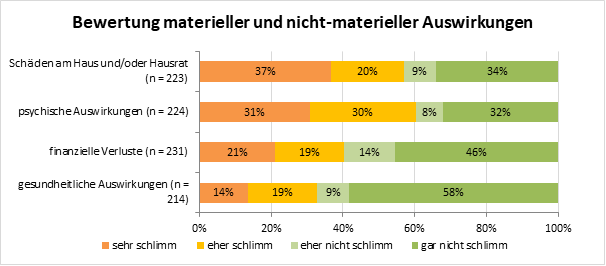

Similarly, a quantitative survey conducted three years after the events in Fischbeck showed that a majority perceived the psychological effects as more severe than the material damages.

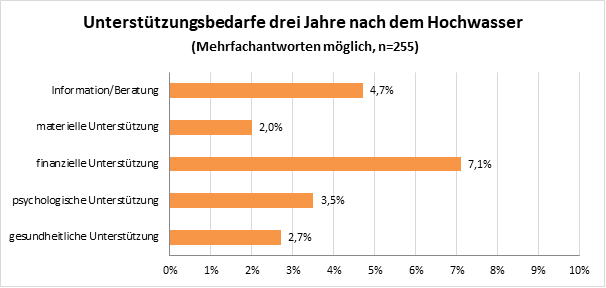

Even three years after the flood, many people still needed support in various areas, especially financial, but also information/advice as well as psychological and/or physical healthcare.

While many of the affected individuals quickly resumed their daily lives, the social shifts and vulnerabilities that such an event contributes to within a community should not be underestimated.

Future Prospects

During the commemorative event in Fischbeck for the 10th anniversary of the floods, political representatives, including Minister President of Saxony-Anhalt Reiner Haselhoff, Environmental Minister Armin Willingmann, and representatives from the State Agency for Flood Protection and Water Management (LHW), emphasized the successes achieved in dike construction and technical flood protection over the past 10 years, technical advancements to be implemented within the coming years.

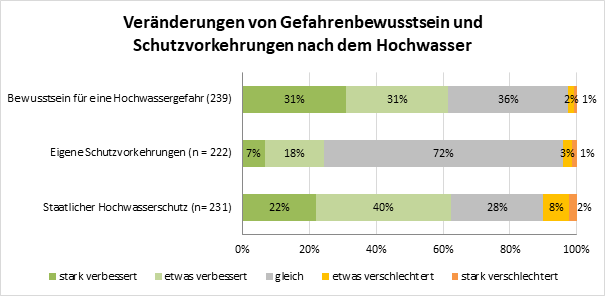

The dike relocation measures initiated shortly after the 2013 events were evaluated positively by the affected population in the 2016 survey, and there was a perceived improvement in trust in governmental measures. While respondents indicated a significantly increased awareness of flood danger—hardly surprising three years after such an impactful event—a comparable rise in individual protection measures is not evident. Apparently, in line with the so-called “dike paradox,” people place trust in technical flood protection measures that make the recurrence of such an event seem highly improbable.

The memorial site established in 2019 at the breach point in Fischbeck focuses on structural measures and the dike. Although the many personal experiences- the ‘terribly beautiful time’ when cut off from the outside world, the numerous helpers, and the damages- were remembered in the commemorative event on June 10, 2023, through an audio compilation; none of this information is visible at the ‘Fischbecker Deichbruch’ memorial site.

On the 10-year anniversary, we were able to discuss our research findings with representatives of the communities and local residents once again. There continued to be a great interest in our work and the results, but at the same time there was a certain scepticism- one shared by us as disaster researchers – about whether faith in technology and a focus on state flood protection measures alone are truly adequate for preventing or coping with future extreme weather events, especially as the magnitude of these is expected to increase, for example in connection with climate change. The dike in Fischbeck is now designed for a flood that exceeds the 2013 flood by one meter. Emergency response plans and flood protection measures in the Ahr Valley had been continuously expanded; there had already been centennial floods in the affected region in 2016 and 2018 (with significantly fewer damages), to which the measures had been adapted to, or in some cases, even made to surpass, such as the flood protection measures of the Eschweiler Hospital. Despite being aware of the dangers, the intensity, extent, and dynamics of the heavy rainfall in 2021 overwhelmed both local and external actors, and the measures taken proved to be inadequate.

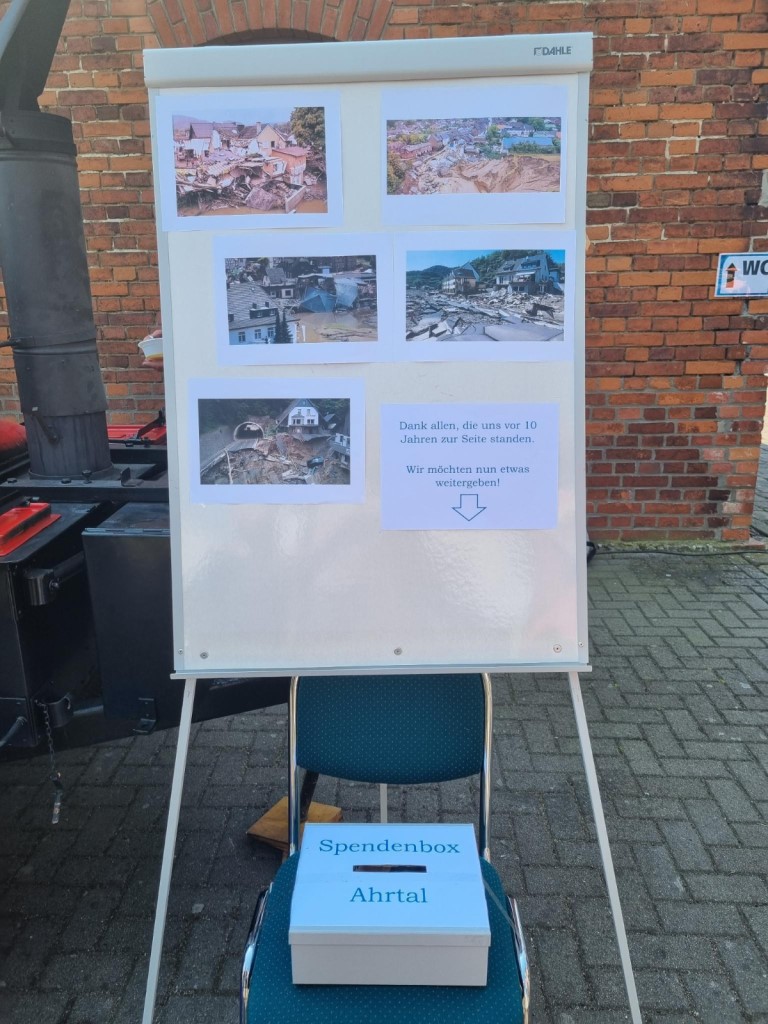

Solidarity with those affected in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate was certainly strong during the commemoration event in Fischbeck, so there is hope that the experiences from Fischbeck can help in other rebuilding efforts after other extreme flood events.

KFS publications on the 2013 flood catastrophe in the Elbe-Havel-Land municipality:

Reiter, Jessica; Wenzel, Bettina; Dittmer, Cordula; Lorenz, Daniel F.; Voss, Martin (2017): Das Hochwasser 2013 im Elbe-Havel-Land aus Sicht der Bevölkerung. Forschungsbericht zur quantitativen Datenerhebung. KFS Working Paper 04. Berlin: KFS. DOI: 10.17169/FUDOCS_document_000000027713

Reiter, Jessica; Wenzel, Bettina; Dittmer, Cordula; Lorenz, Daniel F.; Voss, Martin (2018): The 2013 Flood in the Community of Elbe-Havel-Land in the Eyes of the Population. Research Report of the Quantitative Survey. KFS Working Paper 08. Berlin: Katastrophenforschungsstelle. DOI: 10.17169/FUDOCS_document_000000028852

Schmersal, Elsa; Voss, Martin (2018): Erklärung und Sinnstiftung nach dem Elbehochwas-ser 2013. Narrationen von Betroffenheit, Bewältigung und Verantwortlichkeit. KFS Working Paper Nr. 11. Berlin: KFS. DOI: 10.17169/FUDOCS_document_000000029621

Dittmer, Cordula; Lorenz, Daniel F. (2018): Ausstellungsdokumentation: Was(ser) bleibt? Lokale und wissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf die Flut 2013 im Elbe-Havel-Land. KFS Working Paper Nr. 14. Berlin: KFS. DOI: 10.17169/refubium-925

Reiter, Jessica; Lorenz, Daniel F.; Dittmer, Cordula; Voss, Martin (2017): Vulnerabilität aus der Perspektive der sozialwissenschaftlichen Katastrophenforschung. In: Deutsches Rotes Kreuz e.V. (ed.): Stärkung von Resilienz durch den Betreuungsdienst – Teil 1. Wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse zu Bedingungen für einen zukunftsfähigen Betreuungsdienst, Schriftenreihe der Forschung 4, S. 22-24.

Dittmer, Cordula; Lorenz, Daniel F.; Reiter, Jessica; Wenzel, Bettina (2016): Drei Jahre nach dem Deichbruch – Über die Gegenwart einer nicht abgeschlossenen Katastrophe, Notfallvorsorge 4/2016, S. 17-25.

Kuhlicke, Christian; Seebauer, Sebastian; Hudson, Paul; Begg, Chloe; Bubeck, Philip; Dittmer, Cordula; Grothmann, Torsten; Heidenreich, Anna; Kreibich, Heidi; Lorenz, Daniel F.; Masson, Torsten; Reiter, Jessica; Thaler, Thomas; Thieken, Annegret H.; Bamberg, Sebastian (2020): The Behavioral Turn in Flood Risk Management, its Assumptions and Potential Implications. In: WIREs Water 7 (3). DOI: 10.1002/wat2.1418

Dittmer, Cordula; Lorenz, Daniel F.; Reiter, Jessica; Voss, Martin (2019): Abschlussbericht „Verringerung sozialer Vulnerabilität durch freiwilliges Engagement (INVOLVE)”. Berlin: KFS.

Dittmer, Cordula; Lorenz, Daniel F. (2018): Forschen im Kontext von Vulnerabilität und extremem Leid – Ethische Fragen der sozialwissenschaftlichen Katastrophenforschung, in: Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 19 (3).

Wenzel, B.; Reiter, J.; Dittmer, C.; Lorenz, D.F.; Voss, M. (2016): The Harmonization of People’s Needs and Professional NGO Assistance. The Case of Flooding in Germany. In: Ghafory-Ashtiany, M.; Izadkhah, Y.O.; Parsizadeh, F. (Hg.): Proceedings of Extended Abstracts. 7th International Conference on Integrated Disaster Risk Management Disasters and Development: Towards a Risk Aware Society. Teheran, S. 171-172.