By: Cordula Dittmer and Daniel F. Lorenz

http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/refubium-45264

Original German version published on July 26, 2023

Translated version published on July 31, 2024

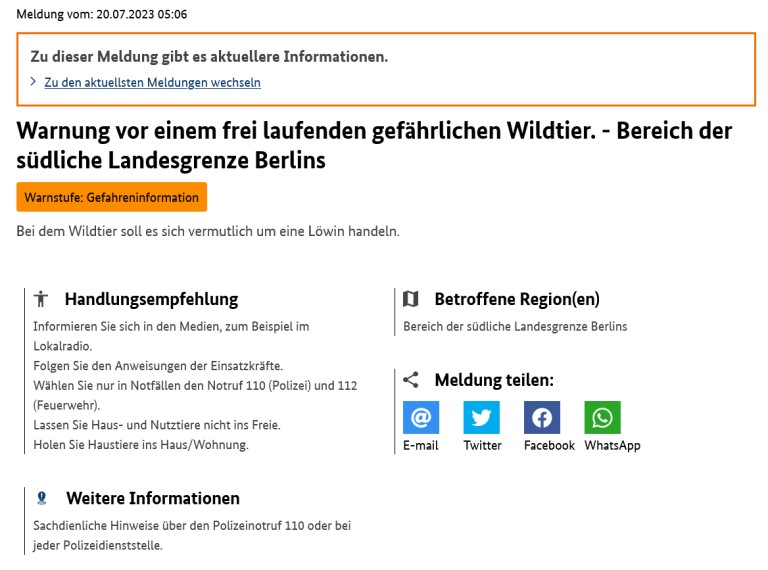

On July 20, 2023, at 4:26 AM, the warning app NINA alerted the residents of the tranquil upper-class enclave Kleinmachnow, located in the south of Berlin, with the message: “Warning of a free roaming big cat.” This message was reiterated at 6:07 AM with the statement: “Warning of a free roaming dangerous wild animal,” accompanied by the additional information: “The wild animal is presumed to be a lioness.”

Source: https://warnung.bund.de/meldungen/alt/mow.DE-BR-B-SE017-20230720-17-000_20230720050621/Warnung_vor_einem_frei_laufenden_gefaehrlichen_Wildtier_Bereich_der_suedliche_Landesgrenze_Berlins

Subsequent warnings urged residents not to leave their homes if possible and to bring pets indoors. The basis for these warnings was a relatively pixelated video taken at night, in which, according to eyewitnesses and the police, a lioness could be seen relatively clearly. The video depicted the lioness feeding on a wild boar, which observers had also seen her hunt.

Based on the video as well as eyewitnesses, a 36-hour search operation was conducted with police officers from Berlin and Brandenburg, veterinary officials, hunters, trackers, and heavy equipment.

The #Lioness was occasionally “spotted,” leading to adjustments in search and safety measures. Precautions included keeping kindergarten children indoors, not setting up stands at the weekly market, and other similar measures. Spectators indulged in the social media buzz, finding pleasure in the somewhat eerie spectacle of a wild animal finding its way into civilization. Various allegories and connections to current political and societal themes were humorously re-examined through the lens of #Lioness.

Why are these series of events so interesting for a sociological consideration of catastrophe?

- “The Emperor’s New Clothes” – or: The Social Construction of Situational Pictures

The interpretation of the image was legitimized by trusted institutions: Both the police and the warning authority (in the form of the Berlin Fire Department via the warning app NINA) offered the population the interpretation that what was shown was a “lion”. Anyone who watched the video with the assumption that it was a devouring lion would also recognize it as such – at least, as long as one was not a wildlife expert. The idea that a lion had strayed into the suburban forests of Kleinmachnow was too tempting to resist. Supported by special broadcasts and live reports, the image was maintained and solidified. As such, the lion was sighted several times by the police themselves, and animal hairs were found. The looming danger was perpetuated by the appearance of security forces, who combed the streets and green spaces with machine guns, protectors, and armored vehicles. Initial doubts about the official interpretation barely made it through. Only after no secure evidence was found was the alternative that it might be a wild boar recognized as a possibility.

“The chamberlains who were supposed to carry the train grabbed at the floor as if they were lifting the train; they walked and acted as if they were holding something in the air; they dared not let it be known that they could see nothing. Thus, the Emperor proceeded in procession under the magnificent canopy, and all the people on the street and in the windows exclaimed, ‘God, how incomparable are the Emperor’s new clothes; what a train he has on his robe, how beautifully it fits!’ No one wanted to admit that they saw nothing, for then he would not have been fit for his position or would have been very foolish. No clothes of the Emperor had been as successful as these. ‘But he has nothing on!’ finally said a little child.” (Hans Christian Andersen 1805-1875)

What Hans Christian Andersen put forward in this fairy tale almost 200 years ago is the bread and butter of the disaster responder: the initial information gathered right after arriving at the incident site, the exploration, is crucial for spatial organization, the development of situational awareness, the request for resources, and the targeted management of the situation, thus determining the course of events of the next few hours: “Once the train is derailed, it can hardly be stopped,” experienced emergency responders report. The power of language and its ability to construct reality is known in sociology through Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann’s “The Social Construction of Reality,” as well as feminist, poststructuralist, or postcolonial theories. Thus, situational awareness, which is the basis of every decision and action, is socially constructed; it depends on the nature and validity of information, communication, trust in the source cof information, etc. This circumstance was particularly evident in the heavy rainfall events in 2021 in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate, where it took local and higher levels of government a long time to realize that this was not just a local heavy rainfall event but a widespread situation that exceeded all previously known damage scenarios. Therefore, one processed the data as one knew how to interpret it – a different, more reality-appropriate understanding emerged much too late.

The #Loewin (German for Lioness) clearly illustrates how rapidly a specific narrative solidifies through the combination of imagery, speaker legitimacy, and social acceptance. This, in turn, shapes actions that are particularly influenced by the characteristics of a crisis, including time pressure and the imminent danger to life and limb. In the best case, there is an overreaction, as seen with the #Loewin; in the worst case, actions may be miscalculated, leading to potential loss of lives.”

2. How do I behave when I encounter a #Loewin – or: Crisis Communication in Unknown Situations

Amidst this time of uncertainty, the reactions demonstrated another lesson in disaster sociology. None of the responsible actors, including the media, had ever experienced nor prepared for such a situation. A concrete emergency response plan or warning strategy for this type of event most likely did not exist. As there was a perceived threat to the population, the Berlin Fire Department decided to issue the appropriate warnings through NINA and KatWarn. An emergency staff team was assembled to deal with this crisis and the Berlin Police provided assistance and communication through public social media channels. Various experts were consulted, and tips were provided to the population on how to behave when confronted with immediate danger. The population was kept informed with live tickers and the local mayor presented developments in the situation in press conferences. State politicians became experts on zoology in the tabloid press. “Affected” residents exchanged information, such as through chat groups, on how to interpret the event, whether animals were in danger, if they should still commute to work or if they should stay home for safety. Those who could, chose to drive rather than bicycle to work.

Image translation: When encountering the Lioness, what should you do?

During an encounter:

No sudden movements

Don’t run away

Stay standing,

Back away very slowly

Stretch your arms side to side,

Try to appear as large as possible

Keep sight of the Lioness at all times

This situation exemplified many established characteristics of crisis communication, particularly those developed during the pandemic. For instance, the ability to stay informed through live news tickers (especially regarding incidence rates during the pandemic), guidance on how much toilet paper to purchase, and live coverage of voting and decision-making processes. Uncertain situations and crises affecting large population groups have increasingly been discussed publicly and in real-time, at least since the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This public crisis communication character exists especially if the phenomena have significant potential for media scandalization and (such as is the case for rapid-onset catastrophes) if they can be managed within defined space and time. This was certainly evident during the pandemic in decisions about lockdowns.

The rise of social media has allowed anyone to become an instant “expert” by sharing relevant photos or videos, posing a significant challenge in managing large-scale situations. It requires additional resources to discern valid information from fake news and/or smear campaigns. Social networks have also become integral to crisis communication efforts, functioning as operational hubs in their own right.

Alongside official efforts by authorities like the police or the mayor of Kleinmachnow to regulate crisis communication on their own websites, a counter-movement emerged on the internet, particularly on Twitter with the hashtag #Loewin. This movement, somewhat termed “counter-crisis communication,” humorously engaged in public discourse about crisis communication. However, this was only feasible because the situation, while posing an abstract threat to life and safety, did not pose imminent danger.

3. The #Loewin (Lioness) as the Queen of the Animals – or: Coherence in Catastrophes

Especially those not personally affected took the opportunity to use the #Loewin as a mirror of societal conditions. Virtually every societal conflict could be humorously discussed and addressed through the metaphor of #Loewin. Whether it was conspiracy discourses from the pandemic skeptic circles (i.e., Querdenker), debates about transgender and queerness, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the growing voices of the AfD, so-called clan crime, or the failures of Berlin politics.

What can be observed here is a phenomenon still relatively unexplored in disaster sociology: the so-called disaster jokes. Although not extensively studied directly, there has been some ethnological research on them, and the popular culture of disaster has already been identified as a research field. In addition to the assumption that jokes can help people cope with traumatic experiences, a thesis postulates that these types of internet jokes about disasters serve to “put disasters back where they are usually found, where we feel they belong and where we want them to stay – in the fictional, pleasurable domain of popular culture”.

Another effect that can be observed with the #Loewin is the possibility of creating coherence among media reports and societal conflicts perceived as highly contradictory. The #Loewin manages to unite all these ambivalences under one hashtag. At the same time, there is the opportunity to comment on (and possibly transform) the discourse without needing official authorship to enter into a discussion. Relevant societal issues can thus be addressed without being seriously politically contested. Media, political, and argumentative boundaries can be overcome and reassembled anew. Many users found it very relieving that the sometimes very deep societal divides seemed temporarily bridged.

That the #Loewin ultimately evolved into something else and turned out to be a wild boar, that too is a known phenomenon of catastrophe: Disasters are social processes that sometimes unfold very rapidly or involve different overlapping phases. Often, the event that triggered the disaster becomes less important over time, and other factors such as compensation, health, or psychological effects come to the forefront. Likewise, other crises and disasters may arise that take precedence and determine the agenda, leading to shifts in evaluation of the series of events. What appeared as an exotic #Loewin was actually quite an everyday wild boar. Everyday problems or societal differences and hostilities did not disappear because of the #Loewin—although this seemed possible for a brief moment.

The wild boars, on the other hand, remain.