Katastrophenforschungsstelle (KFS); numerous Authors

Original German version published on July 15, 2022

Translated version published July 30, 2024

“Not everyone is here in the same now. They are only there on the outside, in that they can be seen today. But this does not mean that they live with the others at the same time. Rather, they carry something from the past with them, which interferes” (translated quote from Bloch 1973: 104)

Immediately after the devastating heavy rainfall events in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate in July 2021, the Disaster Research Centre (KFS) at Freie Universität Berlin published a short statement on the contribution that the KFS has made so far in research projects for the analysis of various flood and heavy rainfall events in the past and how these could also be taken up in current research projects as part of the reappraisal. On the anniversary of the events, the following blog post takes stock of further work carried out since then and presents preliminary results[1].

1. 1 year later – context and criticism

Cordula Dittmer

With this blog post, we are joining the many evaluations, reports, surveys, recommendations and lessons learnt papers and statements that have been published in recent weeks and are still being published. Probably no previous disaster in Germany has been analysed, evaluated and criticised from so many different perspectives and facets. This is of course also and above all due to the very high number of fatalities for Germany, the immense material damage and the predicted decades of reconstruction. The question of how many people’s lives could have been saved with a valid early warning and a reliable warning chain is at the centre of the debate, which continues to be an emotional one. And although this disaster and the reconstruction have been intensively monitored (and in some cases will continue to be in multi-year projects), the results so far after one year are rather sobering: The initially communicated goals of disaster-resilient reconstruction appear to be much more difficult to realise than planned. Instead, to use the words of vulnerability and resilience research, we are seeing a “bouncing back”, i.e. a return to the previous status quo, which has left the affected regions vulnerable to the immense damage. So far, neither a “bouncing-back-better” nor a transformative process can be observed, as recommended by disaster research (e.g. Alexander 2013; Manyena 2006) and, for example, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction for years for reconstruction processes and sustainable disaster risk management.

Furthermore, the disaster in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate illustrates the need for social science, theoretically based disaster research in Germany. Contrary to what continues to be frequently reported in many media, the heavy rainfall events are not a “natural disaster”, but a social disaster, the failure of everyday risk and hazard cultures or even the disaster culture and the associated everyday routines. In order to counteract the potential failure of everyday routines, the field of civil protection and disaster control has historically emerged as an institutionalized practice. This forms special routines which, in the best-case scenario, can anticipate, mitigate or even prevent the failure of everyday routines. In the best-case scenario, these are embedded in a positive disaster culture in which appropriate risk and crisis communication is established, warning concepts are available to the population, vulnerabilities/vulnerable groups in the population are known, emergency units are well prepared and the establishment of a “new” everyday life and corresponding routines is designed to be resilient (see Voss et al. 2022).

However, due to the need to generate quick and easily implementable recommendations, many of the analyses have so far remained at a descriptive level with already known demands for more/better/different equipment, means of communication or responsibilities, many of which already existed before July ’21 (see, for example, the evaluations of the Elbe floods DKKV 2003, 2013). At the same time, for many years there has not only been a much-cited “flood dementia”, but also a societal and politically enforced narrative that singularizes extreme events. Within this narrative, it seems sufficient for disaster management to be reactive: either experience has already been gained with an event and it can be dealt with using established instruments and procedures, or the future is so uncertain that it is impossible to prepare adequately for it – so, to exaggerate, everything remains as it is.

Against the backdrop of current heatwaves, droughts, the Sars-CoV-2 pandemic, natural gas shortages and civil defense scenarios, it is only slowly being recognized politically that the current procedures and processes for coping with such fundamental social shocks and vulnerabilities are no longer sufficient to manage, or at best prevent, current and future challenges. The German government’s recently adopted resilience strategy is a first step in this direction, but it still has to prove itself in concrete implementation.

The severely affected regions, particularly the Ahr valley, but also the towns of Stolberg and Eschweiler, have historically always been confronted with floods or heavy rainfall events. In the narrow river valleys, there are hardly any water retention possibilities per se, anthropogenic influences such as the sealing of surfaces, intensive agriculture, especially through viticulture, road and railway bridges, dam construction, tourism or opencast lignite mining have made the region extremely vulnerable to events of this kind (Szönyi et. al. 2022).

Previous similar heavy rainfall events in the region, such as 2016 in the Ahr Valley or 2018 in the West Eifel, which caused significantly higher economic damage in some districts (see also the section on governance), had already been labelled as “exceptional events”, so that a further increase seemed hardly conceivable and therefore no further preparation was needed. However, those districts that did not follow this narrative and drew conclusions for their heavy rain risk management, e.g. by consolidating disaster control centers as in the Eifelkreis/Bitburg/Prüm district, dealt with the 21 events much better. In public and academic debates, the Ahr Valley often serves as a “discursive nucleus” around which all other affected regions and arguments are (or have to be) grouped – and thus also threaten to be lost from view[2]. This also needs to be considered in the socio-scientific evaluation of coping and reconstruction.

Over the past 12 months, various projects at the KFS[3] have addressed the questions of what mistakes were made before, during and after the heavy rainfall events, what weak points could be recognized, what best practices emerged and what lessons should be learned from them. The affected regions are very heterogeneous, both topographically and socio-economically, so that generalized statements or recommendations about the entire affected area are fundamentally fraught with uncertainty, even if these are desired by politicians and practitioners. The forms of affectedness, processes and methods of coping (social, economic, cultural/symbolic, technical) as well as the temporal and spatial extent were and are very different; different actors can be in different phases of coping – although spatially close.

A differentiated view of the very different social, physical, economic and cultural vulnerabilities is essential in order to adequately map the various dimensions of this disaster and the recommendations that can be drawn from it. Many of those affected, particularly in the Eifel region, report that although they lost everything in the disaster, their attachment to the region or their hometown has only grown stronger as a result of their experiences and, even if the reconstruction is arduous and exhausting, they want to return there or have developed their own rituals to maintain the connection to their home. These social aspects must be included in lessons learnt, just like flood-resistant bridge constructions or the need for retention areas. The focus on the heterogeneity of the events and their institutional, political and social management also makes it possible to broaden the view of where management has worked well, where lessons have been learnt from past situations or where disaster management itself is well positioned. The affected districts could also learn more from each other in this respect.

From the perspective of social science disaster research, civil protection must be thought of much more strongly than before as a complex network that includes very different actors, practices and resources that pursue different interests. Society as a whole needs to accept that civil protection is important at all levels, but that corresponding expectations of it must also be managed and limits to its affordability must be recognized. This applies in particular to the current increasingly complex framework conditions in terms of cascading crises and disasters (e.g. refugee situation, swine fever, pandemic, forest fires). The extent to which vertically organized administrative responsibilities are functional here, particularly with regard to warning chains, should be discussed. Consideration should also be given to developing more horizontal models, such as the organizational principle of safety regions that has been successfully established in the Netherlands.

The population in its heterogeneity and with its social vulnerabilities should be included much more than before in the analyses and processing and trained in their self-help capacities. The first aid courses with self-protection content or the BBK brochures are a first step here, but perhaps it is also worth looking at other countries to see how they sensitize their populations to disasters. At the same time, the state must continue to fulfil its genuine promise of protection and, above all, help those who are unable to help themselves. In order to be able to research complex dangers and challenges of the future as well as societal resilience in a more systemic way, broad-based competences are required that enable real protection of the population, as offered by the concept for competence hubs for resilience and protection of the population. The KFS has made a wide range of further proposals and analyses[SL5] on fundamental weaknesses and necessities of civil protection reform and defined lessons to be learned (Voss 2022).

2. Some findings on the topic of warning

Cordula Dittmer

The early evaluations and lessons learnt papers (e.g. Beinlich 2021) already clearly indicated that warnings were not issued or not passed on, that the potential extent of the possible damage was not communicated clearly enough and that many lives could have been saved if the warning chains and messages had been reliable. From a meteorological perspective, the signs of an exceptional event were very clear and many of the severely affected towns could have been evacuated with some lead time (Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen 2022).

From a more differentiated perspective, case studies in the context of the HoWas21 project show that there were indeed a large number of warnings using different warning methods, which were only perceived and acted upon in very different ways.

The problem was – as far as the current state of the investigation is concerned – on the one hand, that warnings were issued about the heavy rainfall events (and in some cases the potential flood events resulting from them), but not in terms of the amount or intensity, the necessary urgency and, above all, not in the form of flood waves, which, after an initial subsidence of the water levels[4] and the associated initial easing, very surprisingly and quickly poured over the narrow valleys or caused small tributaries to overflow. The question of whether and how specifically the effects, i.e. the impact, of the rain could have been predicted is still the subject of intensive discussions between the various warning organisations, from the German Weather Service (DWD) and the state environmental agencies to the districts. Another major problem was that some of the warnings, if they reached those potentially affected at all, were not taken seriously enough by both the population and those responsible for civil protection, that there had already been several similar warnings beforehand or that the population was aware of the warnings but did not know what action to take as a result (Thieken et. al 2022; Szönyi et. al. 2022). Coherent warning and information concepts coordinated between the district and municipality were rarely available – although they were defined as a genuine task of local self-government in the respective state disaster control laws.

In the area of early warning – depending on the equipment and practice of the region – a warning mix of warning apps, social media[5], sirens, loudspeaker vehicles, personal contact by the local emergency services and personal warnings via social networks was usually used. The different media each reach different target groups that are equipped with different levels of social, economic or cultural capital and (can) react differently accordingly. The WEXICOM I-III projects together with the DWD have been researching for several years (e.g. Schulze/Voss 2020, 2022) that warnings about any type of event should actually be written for specific target groups. The warning tools used in the regions analysed in HoWas21 and the questions that arise from a social science perspective can only be hinted at here.

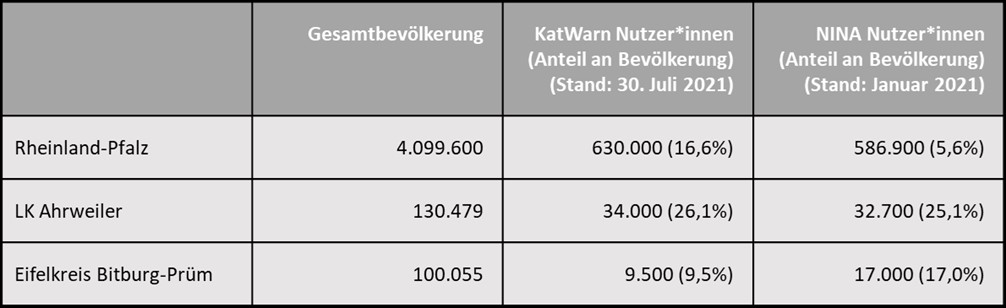

Warning apps KatWarn and NINA: At federal and state level, warnings were issued by disaster control via the two warning apps “KatWarn” (mainly used in Rhineland-Palatinate) and “NINA” (mainly used in North Rhine-Westphalia), and by flood protection via the DWD apps, Meine Pegel, etc., as well as in part, albeit not in a structured manner, via analogue and/or social media. Unfortunately, no valid user figures[6] are yet available for the NINA and KatWarn warning apps. However, cautious estimates based on data that has not yet been validated suggest that the number of users is still rather small and that MOWAS in particular, as a federal system, was not used very actively during the situation.

One of the reasons for this is that some players in local hazard prevention, especially the fire brigades, do not define the large-scale warning of the population as their task, as this often only becomes relevant in the event of major situations (alert level 4 in Rhineland-Palatinate or disaster/major damage situation in North Rhine-Westphalia).

What is already apparent here and also continues in the analysis of the further management: A large number of municipal emergency management teams assumed an incorrect assessment of the situation, working for too long with the situation picture that these were localised emergency sites that could be managed with “on-board resources” at municipal or at least district level and that it was therefore not necessary to warn the population or even evacuate them. When the realisation dawned that this was a much larger-scale incident, in many places it was difficult or impossible to call up the structures intended for this purpose, such as higher-level crisis teams, supra-local assistance, declaration of a disaster situation, etc., as the communication structures had collapsed and all the local emergency services that were actually available were already in action themselves or privately affected. This also led to some desperate phone calls from district administrators to civil protection organisations they knew personally outside the affected area, asking them to send everything they had. After arriving on the scene, these units either acted autonomously without knowledge of any local command structures or sometimes wandered around in search of assignments or waited in temporary staging areas.

Sirens: In some districts, sirens were not dismantled after the end of the Cold War, but continued to be used. However, they were mostly used to alert the fire brigades and, due to the outdated technical equipment, only with a signal that the population only recognised as a fire brigade alert. Although siren warnings were trialled in some villages, these failed for the reasons mentioned above. The expansion of sirens, which is also planned with federal funding, must therefore also be accompanied by an awareness-raising and information campaign about which signals have what meaning and what actions result from them for the population[7].

Vehicles with loudspeakers: Loudspeaker vehicles were a relatively widespread means of warning in many regions, but they are associated with a number of problems. First of all, it is often unclear which fire brigade has which resources that could be used for this purpose. The relevant vehicles must be available and not already involved in other emergency response activities. The crew must be trained in how to drive warning routes and routes must be newly and specifically defined depending on the scenario. It must be anticipated that the crew of loudspeaker vehicles could also be used as a contact point and information portal, and a plan must also be in place for this.

Personal contact by the local emergency services: This requires trust in the respective institutions and individuals, as well as the expertise of the warning person to convince people to leave their homes. This warning method can be very effective, especially in small towns where a large number of people are involved in the fire brigade, but resources are limited. It is also problematic here if the interpretations of what is said differ greatly. This was particularly clear and dramatic in the case of the Lebenshilfehaus in Sinzig, where the different perception of the seriousness of the warning was probably the main reason why many people lost their lives:

“If the statement is to be believed, his warning fell on deaf ears. The LHH carer is said to have refused to evacuate the lower parts of the building, as this would have caused unrest among the residents. He is said to have questioned whether the water could really rise that high. The answer from the fire brigade was that they didn’t know, but it would be better to evacuate the lower wing. When asked about this …, the care home employee described the situation completely differently. The fire brigade had been with him at the time. However, he was only told that the Ahr could burst its banks. Obviously not a warning that gave cause for panic. After all, the LHH is located above the Ahr meadows about 200 metres from the river. The carer reports that he has checked the situation several times since then, but has not noticed any flooding. At half past two at night, the fire brigade informs him that the flood is now on its way. The man tries to save what can be saved” (own translation from Spilcker 2021).

Personal warnings via social networks:

“In the late afternoon, the mayor of Speicher, which is in the municipality near Bitburg at the top of the Kyll, called the mayor of Kordel or Trier, I don’t know exactly when, and said that a bridge had been washed away here and that the flood was coming towards you – it’s just under three or four metres here. As a result, they were able to react quite early and the hospital was evacuated in Ehrang. And thank God, no one was injured” (own translation from expert interview HoWas21).

Warning chains are formally defined according to responsibilities and hierarchies, not according to river courses or valleys. Although warnings were issued via various warning channels, they were often not issued to the locations that were directly affected due to the formal administrative specifications. This applied in particular to regions bordering other federal states from which the water came. Here, personal networks “upstream-downstream”, as in the interview quote above, were of great importance.

3. Governance structures of civil defence and disaster control

Cordula Dittmer

From a social science perspective, civil protection or civil defence and disaster control should be viewed as a functionally differentiated system with highly formalised structures in everyday life/training/preparation and highly informalised structures during operations, as well as very high expectations on the part of society. Civil protection is a social practice that is formed on a situation-specific basis in the event of an emergency, is based on practised rules, procedures and processes and is embedded in disaster (protection) cultures. It is thus spanned within a triangle of “formality – informality – expectation”, within which the preparation for and management of extreme events takes place. This tense relationship must be taken into account when evaluating and analysing civil protection and disaster control; at the same time, it also explains many of the criticisms and weaknesses that have become apparent in disaster management.

In the areas affected in 2021, there were similar heavy rainfall events in previous years, some of which caused worse damage than in 2021 (e.g. Eifelkreis/Bitburg/Prüm district) (Gerlach 2018):

- 27 May – 8 June 2016: Several heavy rainfall events in the district of Ahrweiler, which occur on average no more than once in 100 years.

- 27 May-11 June 2018: Several heavy rainfall events in the Western Eifel/Volcanic Eifel/Hunsrück with return periods of well over 100 years.

In contrast to 2021, however, these were very localised and no human lives were affected. As a result of these events, a working group on heavy rain events (AK Katastrophenschutz im Innenministerium RLP (ADD Trier 2020)) was set up at state level in Rhineland-Palatinate, which, in cooperation with operational players from civil defence and disaster control, supplemented the Framework Alert and Response Plan for Floods (RAEP) with a new “Annex 18: Operational Instructions for Coping with Heavy Rain Events” (Ministerium des Innern und für Sport Rheinland-Pfalz 2020). This was intended to form the basis for the creation of separate hazard prevention plans for local authorities (districts/district-free cities, municipalities). A further mandate from the state to the districts and municipalities was to draw up a warning and information concept for the population “in the event of major hazards” in consultation with municipalities and the district. This was to be updated every five years and take particular account of vulnerable groups (children, people with physical, mental or psychological impairments) (LBKG 12.02.2022).

In many districts, these requirements have not been implemented; others, especially those bordering rivers, have a RAEP flood plan but no supplement with a heavy rainfall concept. A coherent warning and information concept for the population is also rarely available. In the HoWas21 project, the KFS analysed the reasons that prevented implementation, which are briefly outlined here:

1) Heavy rainfall events as normality; 2) Predictability of impact; 3) Tendency to “blame game”; 4) Lack of sanction options and controls; 5) Delay due to pandemic; 6) Focus on fire brigades.

1) Heavy rainfall events as normality

Heavy rainfall events occur relatively frequently and are part of everyday operations for local emergency response teams. They can almost always be dealt with using the resources of the local volunteer or professional fire brigades, even if, as there are often a large number of emergency sites, supra-local assistance is often required. The fire services therefore have a wide range of experience with these often technically not very demanding operations, which are, however, usually time-consuming and resource-intensive (Kutschker 2019). Special features or distinctions from a flood damage situation are rarely seen, and the RAEP Hochwasser for Rhineland-Palatinate does not provide for these either. A heavy rainfall situation with the corresponding advance warnings therefore did not in itself represent a worrying situation for local hazard prevention, especially as the specified water volumes and runoff calculations could hardly be interpreted or transferred to local contexts in some cases.

2) Predictability of impact

The interpretation of technical data in the context of weather warnings is a prerequisite. A corresponding precautionary heavy rain concept with a hazard and risk analysis is required in advance. This requires expertise and financial and human resources on the part of the civil protection actors. These are not available across the board at municipal or district level or at the level of independent cities. Here, the majority of civil protection work is based on voluntary work (see the section on voluntary work), or the weekly hours allocated to this by the relevant regulatory authorities are minimal. Nevertheless, the RAEP Floods and the State Disaster Protection Act in Rhineland-Palatinate, for example, require that such risk and hazard analyses be carried out at municipal level. This is the only place where the relevant local knowledge is available to adequately manage the situation. However, if you ask at the relevant local level (district/city/municipality), the responsibility or even the possibility for this type of impact-based prediction is sometimes denied:

“So if you look at the vegetation phase, one year I have a field with maize and the next year I have a field with wheat or rye. And depending on how much it has already grown, is it freshly planted, when are these thunderstorms coming, so you can’t weigh up everything from the outset in the assessment of how it will be reflected in the impact afterwards” (quote translated from expert interview HoWas21).

3) Tendency to “blame game”

As can be seen in the section above, there is a tendency among the various levels of civil protection to play the “blame game”, i.e. to assign blame or responsibility to one another. Although a lack of/unclear responsibilities is criticised regularly and also in the review process, the division of tasks between different players, which is sometimes laid down by law, can be used strategically to get rid of unpleasant tasks or tasks that cannot be completed for resource reasons. This can be seen very clearly in the aforementioned discussions about the creation of a coherent warning concept, which in Rhineland-Palatinate is to be located at the interface between the local authority and the district (“in coordination with …”) and is therefore the subject of negotiations:

“In the opinion of the local fire brigade leaders, warning the population in advance cannot be the task of the fire brigade” (Quote translated from German, VG Bitburg 2020: 86).

Another difficult situation arises for regions on the border with other federal states when the floodwaters come directly from the neighboring federal state. The warning system, as part of disaster control, is also federally organized, resulting in a lack of structured inter-state warning concepts:

“Yes, right here at the state border to North Rhine-Westphalia. We received the main bulk of water from North Rhine-Westphalia, where up in the heights, 220 liters per square meter fell, while down here with us, it was only 170 within 24 hours. You can imagine what arrives here. But due to the state border between Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia, there is no exchange of any messages or hints or anything else” (Quote translated from expert interview HoWas21).

4) Lack of sanction options and controls

Another problem is that the state does not have technical supervision over disaster control; it is the legal duty of municipal self-administration to take care of disaster control and local hazard prevention. If no control and sanction mechanisms are provided, in regions where local administrations are already underfunded, disaster control or local hazard prevention, which are relatively costly items, are not given high priority.

5) In progress/delayed

In some municipalities, as a result of initiatives by the state governments of Rhineland-Palatinate, heavy rain concepts were developed. This development process is a complex procedure, so the creation, including the necessary expert opinions and the involvement of the affected population, can take several years:

“There was a heavy rain concept created in the wake of the 2016 events, which has now been completely discarded. Because we saw that the water flowed in completely different ways than we had imagined. Actually, the presentation of it was delayed first by Corona. Then the flood came, and it was moot anyway, now we have to make a new one” (Quote translated from expert interview HoWas21).

This clearly shows that even the existence of a concept is no guarantee that damage will be prevented.

6) Focus on fire brigades

A fundamental issue in the field of local hazard prevention planning is that it falls solely within the jurisdiction of the fire departments. Due to their often very clear technical training and well-defined mission, they may have limited knowledge of social vulnerabilities and the contributions that the so-called “white” organizations could make in managing a situation. The dominance of the fire departments is also evident in the available reports and lessons learned, which rarely incorporate the perspective of other aid organizations such as the German Red Cross (DRK) or the Workers’ Samaritan Federation (ASB). Much criticism has also been directed at the fire departments in handling the situation. Although they are well-equipped both technically and personnel-wise, their involvement typically concludes with the completion of their work, whereas aid organizations may only enter the scene afterward.

4. Volunteering, spontaneous helpers, and civil society engagement

Sara T. Merkes; Theresa Zimmermann

The project ATLAS-ENGAGE, funded by the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance (BBK), explores, through a meta-analysis against the backdrop of changing societal conditions and trends, the various facets of engagement. It examines research- and practice-based concepts for incorporating different types of engagement, from traditional volunteering to acute spontaneous assistance, into civil protection.

Disaster relief in Germany relies heavily on volunteers: The actors collaborating in civil protection roughly count on about 2 million volunteers[8] nationwide. These volunteers are involved in the Federal Agency for Technical Relief (THW) and the volunteer fire departments, as well as the civil society aid organizations mentioned in the Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance Act (ZSKG 1997) – ASB (Workers’ Samaritan Federation), DLRG (German Life Saving Society), DRK (German Red Cross), Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe (St. John Accident Assistance), and Malteser Hilfsdienst (Malteser Aid Service). In the context of handling the heavy rainfall events of 2021, in the first weeks and months, more than 12,000 personnel from the aforementioned aid organizations were involved (BMI and BMF 2021). Furthermore, the THW, as a primarily volunteer-supported federal agency, was active until July 2022 with 17,000 THW members and approximately 2.6 million hours of operation (THW 2022). Additionally, numerous firefighters from professional and volunteer fire departments, more than 7,800 forces from the Federal Police and Federal Criminal Police Office, as well as over 2,300 Bundeswehr (German Armed Forces) members in official assistance, were involved (BMI and BMF 2022). They all are part of the official disaster response.

In addition to the official emergency services, according to estimates by the Federal Ministry of the Interior and the Federal Ministry of Finance, by the time their report was published in March 2022, about 100,000 private helpers, partly organized in initiatives, existing or newly founded networks, associations, and spontaneously formed support communities, were active (BMI and BMF 2022). This commitment, although most pronounced immediately following the heavy rain events – with up to 2,500 helpers per day being registered by the Helper Shuttle alone on summer weekends (SWR 2021) – extends far beyond immediate assistance and continues to contribute significantly to reconstruction: The Helper Shuttle, operating locally in the Ahr valley, counted more than 125,000 helpers [9] and almost one million working hours by the end of May 2022 (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2022). In short, voluntary commitment in the context of the heavy rain events – whether in officially organized operations or within civil society networks – was enormous and can be seen as an essential component of societal resilience to crises and disasters (cf. Krüger and Albris 2021).

A major challenge that still exists, despite individual efforts and intensive engagement with the topic by civil protection actors since at least the flood events of 2013, is the integration of these two strands of disaster management, i.e., the official, organizationally bound civil protection deployment and the private, civil-society, neighborhood-based, and/or spontaneously organized aid initiatives (cf. IM NRW 2022, 14). While the official deployment already requires the cooperation and coordination of a multitude of different deployment organizations, the more informal help is even more fragmented and diverse, although there are indeed also centralizing actors and networking offers (cf., for example, Helfer-Stab 2022): The Flood Wiki (2022) alone comprises more than 800 groups and pages, which is certainly also due to the large and cross-regional situation, because in addition to the supra-regional or professionally or sector-focused aid initiatives, a large number of locally anchored aid communities were established (as of March 2022, own count).

It is notable that the majority of at least recorded networks of private initiatives rely on social media as communication and coordination channels, making them accessible and communicable to a wider public beyond the local community. This means that resource pooling networks are deeply woven into the World Wide Web, allowing aid communities to act independently of location. Digitalization expands the possibilities and limits of missions and initiatives on the one hand, and on the other hand, internet-based activities develop into a second virtual site of deployment with its own needs, which civil protection organizations can no longer ignore, such as in terms of situation awareness, crisis communication, and public relations.

Another point is the hybridity of private actors: In the management of the flood situation in 2021, it was not uncommon for volunteers affiliated with civil protection organizations to get involved in situation management and assistance as private individuals with their knowledge and networks, in addition to or beyond their officially requested deployment. Aid actors use their resources and roles flexibly, drawing on both professional and private networks, including by adopting the most conducive role at the moment. For example, in an interview, we were told about the mayor of a small town who primarily contributed privately but issued donation receipts in his capacity as mayor when necessary. In another case, a member of the Bundeswehr took leave for private assistance but acquired resources through professional contacts, proved his expertise to the official response organizations with his service ID, and through his superior, psychosocial support was made available to him and other private helpers by Bundeswehr personnel.

The civil society response to the heavy rain events relied on both existing professional and private networks and associations – for example, thanks to their connections, farmers with their tractors and trailers were able to stand by for evacuations, such as that of the Eschweiler hospital, within a short time – and initiatives and aid communities developed from the situation itself, such as the establishment of the helper shuttle to address the traffic problem.

Based on our research, we assume that these hybrid and spontaneous forms of aid and networks are widely spread and, considering the tendency towards more complex, hybrid, and prolonged operational situations, will gain in importance. Given the existence of resources, opportunities for cooperation, and coordination channels, the innovative and creative development and coupling of civil society, private, and also corporate-based aid initiatives are not surprising and, if not concrete, still predictable in their likelihood of acting in a disaster situation. For example, a survey among the Berlin population showed that 88% of respondents would be willing to help in the event of a disaster, while 55% expressed their willingness to take in strangers into their homes in the event of a disaster, and 94% stated they would be willing to provide food and clothing (Lorenz et al. 2015).

Our thesis is that the societal management of disasters is as complex and diverse as society itself. It cannot be understood in isolation from official, institutionalized structures, informal social networks, or professional contexts. In recent years, society has undergone massive changes in its functional and operational mechanisms, which also shape engagement and sometimes require new solutions or the adaptation of governmental structures and disaster management institutions. Changes are becoming apparent in preferred forms of engagement, transnational dependencies, and consequently volatile, vulnerable conditions, societal conflicts, and the politicization of humanitarian concerns and areas of assistance, new and old patterns of vulnerability, as well as changes in the perception of dangers and one’s own opportunities for engagement, which could potentially have a long-term impact on disaster culture.

To understand and anticipate the developments of forms of engagement and networks, as well as the resulting opportunities and necessities for cooperation, it is also necessary to engage with societal developments, including: the aging but also diversification of society, spatial differences and increasing mobility (both in daily life and lifestyles), stressed ecosystems, and dangers changing due to climate and societal structures, new guidelines and protection regulations, technologization and digital networking of Critical Infrastructures beyond the national context, flexible work environments and transformations of knowledge, individualized living environments on one hand but also new forms of collective action on the other.

5. Case study: Hospital evacuation in Eschweiler (North-Rhine-Westphalia)

Nicolas Bock; Sidonie Hänsch; Anja Rüger

As a result of overflowing bodies of water, several hospitals threatened by the water had to be evacuated in the affected federal states, including in Leverkusen, Trier, and Eschweiler. For the research project RESIK, which investigates hazardous situations and evacuation processes in the critical social infrastructure of “hospital” and aims to increase the resilience of healthcare facilities against flood scenarios, the flood disaster of 2021 was therefore of particular investigative interest. Research on the complete evacuation of hospitals could until then be primarily conducted along the flood disaster of 2002 in Dresden. The events of the last year allowed the project to develop comprehensive, new insights into the research topic. The focus was on St. Antonius Hospital in Eschweiler, North Rhine-Westphalia, which had to be completely evacuated on July 15, 2021, due to the isolation of the building by floodwaters and a concurrent flooding of the lower floors as well as the supply and technical rooms.[10] Although the hospital had significantly better structural flood protection measures than those prescribed by the valid flood maps, the facility was flooded by the extreme high water, a scenario none of the respondents surveyed by KFS had previously considered conceivable.

Following the events, the KFS conducted interviews with hospital staff, Eschweiler emergency services, and representatives of the local population. Based on this, the KFS was able to model the events surrounding the hospital and draw conclusions regarding hospital emergency management, interfaces, and communication between the involved actors, and general evacuation processes.

Depending on their personal experience with flood situations, their place of work, and their specific focus of activity, assessments of the danger situation, the resources needed, and the measures to be taken varied significantly. For example, measures related to water rescue and the evacuation of intensive care patients were initially deemed more urgent by the hospital’s incident command than by the Eschweiler fire department, which, unlike the hospital, had to consider the distribution of resources across the entire urban area. Additionally, the late allocation of helicopters for the evacuation of intensive care patients by the crisis team of the Aachen city region caused incomprehension on the part of the hospital, even though here too, the extensive area affected and weather-related restrictions led to a scarcity of resources and options. The interviewees speculated that the different involved bodies, being spatially separate and having situational and operational differences, might have had diverging pictures of the situation due to technical communication difficulties, different professional focuses and idioms, and spatial distance between the decision-making bodies. It was only slowly that a common understanding of the situation at the hospital and the measures to be taken emerged. Employees who had knowledge of both the workings and structures in the hospital and in disaster relief organizations – e.g., emergency doctors and senior emergency physicians – proved extremely valuable in this situation as they could act as a kind of “interpreter” between the two groups of actors. The interviewees mentioned that the organization of the rescue service at the municipal level led to disadvantages in the situation, as the spatial-organizational limitation meant that overarching interfaces and structures, as well as communication possibilities, were little known.

Another coordination challenge was organizing transport: the evacuation of intensive care patients would have been advisable even before the hospital’s isolation, anticipated by local staff, occurred. However, efforts in this regard failed due to a lack of available ground and air transport. The search for destination hospitals for evacuated patients was mainly conducted by phone by the hospital – given the situation and not knowing the conditions beyond their immediate area of influence at the hospital, the responsible parties believed this task would have been more appropriately assigned to the crisis team of the city region, which would have had a better overview of the overall situation and capacities. Communication between the hospital and the rescue service also needed improvement, as not all patients could be transferred to suitable destination hospitals.

The evacuation of the hospital was swiftly executed through the collaboration of spontaneous volunteers, disaster relief services, and the hospital itself. The evacuation of patients not in intensive care was largely carried out using improvised transportation means provided by local farmers (tractors/trailers), which, unlike standard ambulances and emergency vehicles, had a certain level of water fording capability. The organization of transport and coordination of volunteers from the agricultural sector were mainly facilitated through established local social networks and improvised on-site coordination. However, from the perspective of unaffiliated volunteers, there was a lack of clear structure regarding responsibilities, hierarchy, and points of contact within the city/emergency services (see also the section on volunteering).

Another problem was bringing in rested personnel to relieve the forces from the hospital and disaster relief. Some key decision-makers were on-site for up to 70 hours. Alerting fresh forces and staff members, especially those from outside the area, proved to be systemically time-consuming and partly ineffective, particularly as command support units were scarcely available. Inducting new forces turned out to be extremely complex, as was accessing the hospital operation site due to the extensive area affected – a condition that persisted for weeks in some cases.

Since hospital operations are now subject to market economic principles, the management is under particular pressure to keep the hospital running as long as possible or to reopen it as quickly as possible. While investments in hospitals as critical infrastructure are a matter for the states, in the event of insolvency, the managers are solely liable. For example, resuming hospital operations as quickly as possible after cleanup, using emergency power generators, was extremely delicate from a bankruptcy law perspective and associated with enormous personal risk for the managing director.

Further challenges arose from general structural and architectural aspects. For instance, the architectural placement of critical operational facilities such as emergency power, server systems, and other vital installations in basements or ground floors is impractical for emergencies in clinics at risk of flooding or heavy rainfall. Likewise, the digitalization of patient records, medical letters, medication lists, etc., without the ability to extract these data from the system after a power failure or to have an analog fallback option, can prove to be extremely disadvantageous in such situations. The same applies to the communication equipment of the hospital incident command – a secured, uniformly accessible communication link to the “outside,” for example, to the crisis staff or fire department command, is necessary to coordinate a joint approach over a longer period – even in the event of power failures. In the situation of the Eschweiler hospital’s isolation, only the use of private mobile phones and power banks, as well as personal contacts between the actors and organizations, could keep the communication channels open.

In summary, it can be said: The water masses caused by heavy rainfall and the resulting flooding revealed cascading effects of interface deficiencies between different organizations, thereby increasing the physical and psychological strains on the involved actors.

Literature/Further Publications on the Topic

ADD Trier (2020): AG Starkregen. Einsatzhinweise Starkregen Sachstand. Available online at https://bks-portal.rlp.de/sites/default/files/og-group/35719/dokumente/2019_03_14_Hochwasser%20als%20Einsatzszenario%20in%20RLP.pdf, last checked on 15.07.2022.

Beinlich, Wilko (2021): Konzeptionsanalyse BayZBE: Lesson Learnt des Ahrtal Hochwassers Juli 2021. Bayerisches Zentrum für besondere Einsatzlagen gGmbH.

Bloch, Ernst (1973): Erbschaft dieser Zeit. Suhrkamp.

BMI; BMF (2021): Zwischenbericht zur Flutkatastrophe 2021: Katastrophenhilfe, Soforthilfen und Wiederaufbau. Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat; Bundesministerium der Finanzen.

BMI; BMF (2022): Bericht zur Hochwasserkatastrophe 2021. Katastrophenhilfe, Wiederaufbau und Evaluierungsprozesse. Bundesministerium des Inneren und für Heimat; Bundesministerium der Finanzen.

DKKV (2013): Das Hochwasser im Juni 2013. Bewährungsprobe für das Hochwasserrisikomanagement in Deutschland. DKKV.

DKKV (Hg.) (2003): Hochwasservorsorge in Deutschland. Lernen aus der Katastrophe 2002 im Elbegebiet. Deutsches Komitee für Katastrophenvorsorge. Deutsches Komitee für Katastrophenvorsorge e.V (Lessons learned, 29).

Flut-Wiki (2022): Hilfsplattformen. Available online at https://www.flut-wiki.de/w/Hilfsplattformen, last updated 22.03.2022, last checked on 30.03.2022.

Gerlach, Nicole (2018): Starkregenereignisse im Mai/Juni 2016 und 2018. Available online at https://lfu.rlp.de/de/infos-zum-herunterladen/fachveranstaltung-starkregen-und-hochwasserschutz/, last checked on 15.07.2022.

Helfer-Stab (2022): Helfer-Stab Hochwasser Ahr. Available online at https://helfer-stab.de/, last checked on 08.07.2022.

IM NRW (2022): Katastrophenschutz der Zukunft. Abschlussbericht des vom Minister des Innern berufenen Kompetenzteams Katastrophenschutz. Ministerium des Innern Nordrhein-Westfalen. Düsseldorf.

VG Bitburger Land (2020): Entwurf – Starkregen- und Hochwasservorsorgekonzept für die Ortsgemeinde Dudeldorf. Available online at https://dudeldorf.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Entwurf_Hochwasservorsorgekonzept_Dudeldorf.pdf, last checked on 15.07.2022.

Krüger, Marco; Albris, Kristoffer (2021): Resilience unwanted: Between control and cooperation in disaster response. In: Security Dialogue 52 (4), pp. 343–360.

Kutschker, Thomas (2019): Flächenlagen nach Starkregenereignissen – Die Feuerwehr an der Belastungsgrenze. In: BBK Bevölkerungsschutz 2, pp. 6–11.

Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen (2022): Zwischenbericht des Parlamentarischen Untersuchungsausschusses V (“Hochwasserkatastrophe”). Drucksache 17/14944. Available online at https://opal.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument/MMD17-16930.pdf.

Landtag Rheinland-Pfalz (2021): Hochwasserkatastrophe in Rheinland-Pfalz – Kommunikation, Warnung und Prävention. Antwort des Ministeriums des Inneren und für Sport auf die Große Anfrage der Fraktion der AfD – Drucksache 18/774.

LBKG (12.02.2022): Landesgesetz über den Brandschutz, die allgemeine Hilfe und den Katastrophenschutz (LBKG). Fundstelle: GVBl. 1981, 247. Available online at https://landesrecht.rlp.de/bsrp/document/jlr-Brand_KatSchGRPrahmen, last checked on 17.02.2022.

Lorenz, Daniel F.; Dittmer, Cordula. (2021): Disasters in the ‘Abode of Gods’—Vulnerabilities and Tourism in the Indian Himalaya. In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 55. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102054

Lorenz, Daniel F.; Schulze, Katja; Wenzel, Bettina; Voss, Martin (2015): Hilfsbereitschaft im Katastrophenfall. In: Notfallvorsorge 46 (3), pp. 12-19.

Manyena, Siambabala (2006): The concept of resilience revisited. In: Disasters 30 (4), pp. 434-450.

Ministerium des Innern und für Sport Rheinland-Pfalz (2020): Rahmen- Alarm und Einsatzplan Hochwasser. Available online at https://bks-portal.rlp.de/sites/default/files/og-group/57/dokumente/RAEP%20Hochwasser%20Stand%2018.08.2020_0.pdf, last checked on 15.07.2022.

Rüger, Anja; Bock, Nicolas; Dittmer, Cordula; Merkes, Sara T.; Voss, Martin (2022): Die Evakuierung des St.-Antonius-Hospitals Eschweiler während der Flutereignisse im Juli 2021. KFS Working Paper Nr. 25. Berlin: Katastrophenforschungsstelle (in preparation[SL19] ).

Schulze, Katja & Voss, Martin (2022). Weather Forecast and Weather Warning Preferences in Germany. Results of a national representative study. KFS Working Paper Nr. 24. Berlin: Katastrophenforschungsstelle. Download.

Schulze, Katja; Voss, Martin (2020): Sturm „Sabine“ – Wahrnehmung der Warnungen und Reaktionen. Ergebnisse einer deutschlandweiten Bevölkerungsbefragung. KFS Working Paper Nr. 18. Berlin: Katastrophenforschungsstelle. Download.

Spilcker, Axel (2021): Flutkatastrophe: Als Ermittler ins Brackwasser steigen, finden sie erste Leiche. In: FOCUS Online, 13.12.2021.

Süddeutsche Zeitung (2022): Online-Hilfe statt Helfershuttle im flutgeschädigten Ahrtal. Hochwasser – Grafschaft. Available online at https://www.sueddeutsche.de/panorama/hochwasser-grafschaft-online-hilfe-statt-helfershuttle-im-flutgeschaedigten-ahrtal-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-220505-99-166891, last updated on 05.05.2022, last checked on 08.07.2022.

SWR (2021): Viele Tausend Helfer im Ahrtal – doch Zahlen sinken vor dem Winter. Drei Monate nach der Flut. Südwestrundfunk. Available online at https://www.swr.de/swraktuell/rheinland-pfalz/koblenz/helfer-flut-vor-dem-winter-100.html, last updated on 06.10.2021, last checked on 08.07.2022.

THW (2022): Ein Jahr nach Starkregen „Bernd“. Größter Einsatz in THW-Geschichte. Technisches Hilfswerk. Available online at https://www.thw.de/SharedDocs/Meldungen/DE/Pressemitteilungen/national/2022/07/pressemitteilung_001_pm_starkregen_lang.html;jsessionid=6AE06CA6B652A3B85E7BF626EE9289BF.2_cid388?nn=7059670 , last updated on 01.07.2022, last checked on 08.07.2022.

Voss, Martin (2022): Zustand und Zukunft des Bevölkerungsschutzes in Deutschland – Lessons to learn. KFS Working Paper Nr. 20 (Version 4). Berlin: Katastrophenforschungsstelle. Download.

Voss, Martin; Dittmer, Cordula; Schulze, Katja; Rüger, Anja; Bock, Nicolas (2022): Katastrophenbewältigung als sozialer Prozess: Vom Ideal- zum Realverständnis von Risiko-, Krisen- und Katastrophenmanagement. In: Notfallvorsorge (1), pp. 22-32. Download.

ZSKG (1997): Gesetz über den Zivilschutz und die Katastrophenhilfe des Bundes. Zuletzt geändert durch Elfte Zuständigkeitsanpassungsverordnung vom 19.06.2020 (BGBl. I S. 1328).

[1] This blog post is a collective work of different authors from various projects. To make the attribution transparent for the readers as well, the individual sections are marked with different authors.

[2] In dealing with the “Himalayan Tsunami” in 2013 in Uttarakhand, India, interestingly, very similar developments were observed (Lorenz/Dittmer 2021).

[3] Warning processes and cultures, especially the warning of extreme weather events, are currently at the core of the WEXICOM III project as well as in HoWas21. The TsunamiRisk project is dedicated to the study of institutional warning processes. INCREASE plans an analysis of flood events in Germany. The goal is to draw insights from recent flood experiences in Germany and derive lessons learned for an integrated disaster risk management (IKRM). The ATLAS-ENGAGE project addresses how spontaneous volunteers, new and old forms of volunteer engagement, and overall societal developments in disaster situations like the heavy rainfall events of ’21 can be integrated and what concepts exist for involving and strengthening various forms of engagement in disaster response. The deployment of civil protection and disaster relief organizations in the preparation and management of the heavy rain events of ’21 is examined by the HoWas21 project. The RESIK project focuses on hospital evacuations and the importance of critical infrastructure in hospitals during flooding situations.

[4] The fact that the flood models and water level measurements were inadequate for such events, and that there were also massive problems with forecasting or at least with translating the purely technical data into local impacts, is not discussed in detail here, but is thoroughly examined in the HoWas21 project.

[5] The area of social media is not considered in the following, as it is very complex and diverse, and so far, no conclusive results are available.

[6] There are no official download numbers for the warning app “KatWarn.” However, the total number of users, as well as their distribution across individual counties, can be named in a major inquiry to the state parliament of Rhineland-Palatinate. Likewise, no download numbers can be provided for the warning app “NINA,” but users can be evaluated based on subscribed locations. In contrast, it is not possible to quantify users who were actually present on-site at the time of the warnings (State Parliament of Rhineland-Palatinate 2022).

[7] The Academy of the Disaster Research Center (AKFS), a non-profit spin-off from the KFS, is currently conducting a pilot project in the StädteRegion Aachen, in which the installation of sirens is accompanied by communication science research.

[8] The number of volunteers actually available and ready for deployment in civil protection is difficult to quantify but is overall significantly less than the estimated 2 million volunteers. This is also because volunteering in aid organizations is not limited to civil protection, and not all those recorded as volunteers possess deployment capability in terms of completed training, health protection, and valid certifications, such as first aid proofs.

[9] Multiple counts possible/likely

[10] A detailed account of this case study can be found in: Rüger, Anja; Bock, Nicolas; Dittmer, Cordula; Merkes, Sara T.; Voss, Martin (2022): The Evacuation of St. Antonius Hospital Eschweiler During the Flood Events in July 2021. Working Paper No. 25. Berlin: Disaster Research Center (in preparation).