Im Mittelpunkt des zweiten Stakeholder-Workshops des Projektes Open4DE standen die Herausforderungen und Chancen der Umsetzung von Open Access aus Perspektive der Fachgesellschaften

Das Projekt Open4DE, Stand und Perspektiven für eine Open-Access-Strategie für Deutschland erhebt auf der Grundlage einer qualitativen Auswertung von Policy-Dokumenten den Umsetzungsstand von Open Access in Deutschland. Im zweiten Schritt entwickelt das Projekt im Dialog mit den wichtigsten Stakeholdern im Feld Empfehlungen für eine bundesweite Open Access-Strategie. Bereits im Januar fand in diesem Rahmen ein Workshop mit dem scholar.led-network Netzwerk statt. Am 24. Mai 2022 waren Vertreter*innen der Fachgesellschaften zu einer gemeinsamen Diskussion eingeladen.

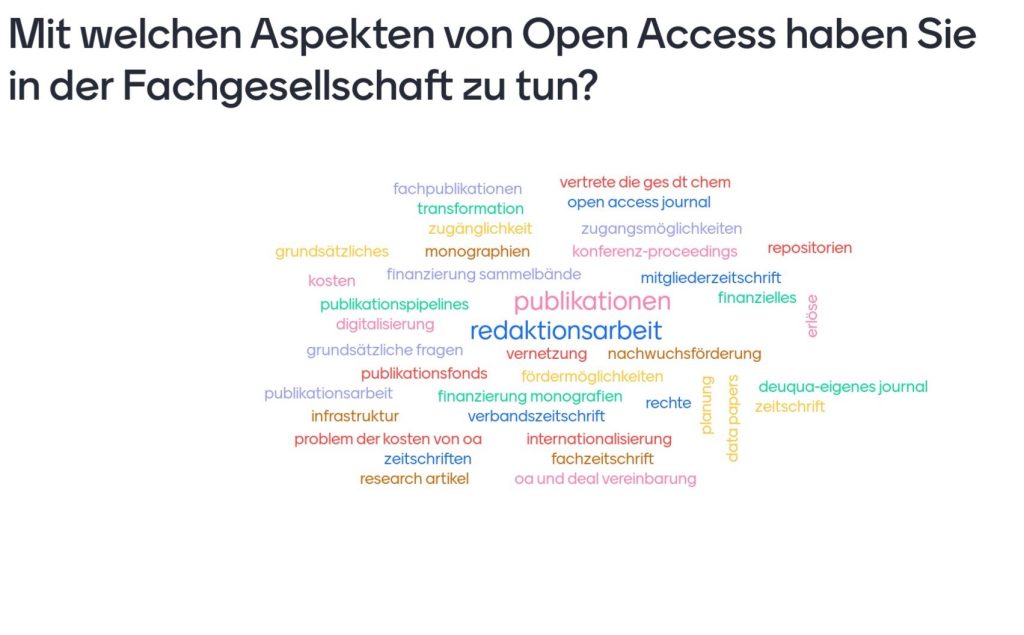

Rund zwanzig Fachgesellschaftsvertreter*innen aus geistes-, sozial-, und naturwissenschaftlichen Organisationen waren der Einladung von Open4DE gefolgt, darunter viele, die insbesondere mit den organisationseigenen Publikationen befasst sind, aber auch Mitarbeiter*innen der Geschäftsstellen und Vorstandsmitglieder. Im ersten Teil des Workshops stellte das Projekt Open4DE seine Ergebnisse aus der Untersuchung des Umsetzungs- und Diskussionsstandes von Open Access und Open Science in den Fachgesellschaften vor.

Umsetzungsstand von Open Access in den Fachgesellschaften

Open Access setzt sich, verbunden mit unterschiedlichen fachlichen Publikationskulturen, in wissenschaftlichen Disziplinen ungleich durch (vgl. z.B. Severin et al. 2022). Während die Physik bereits in den frühen 1990er Jahren eigene Publikationsinfrastrukturen für die fachinterne Zirkulation von Preprints aufbaute (arXiv), spielt in anderen wissenschaftlichen Disziplinen bis heute die Monographie eine zentrale Rolle.

Förderlich für die Aufgeschlossenheit gegenüber Open Access ist ein hoher Nutzen des offenen Zugangs zu digitalisierten Daten (wie z.B. in der Archäologie). Auch die transnationale Vernetzung von Fachdisziplinen mit ärmeren Ländern fördert die Akzeptanz von Open Access. Teilweise sind es eher die kleinen Fächer, die Vorreiter von Open Access und Open Science sind, da sie besonders von einer höheren Sichtbarkeit und einer freien Dissemination ihrer Daten profitieren (vgl. Arbeitsstelle kleiner Fächer 2020).

Policy-Papiere mit konkreten Handlungsanleitungen zur Umsetzung von Open Access haben Fachgesellschaften nicht verabschiedet. Einige Fachgesellschaften bringen sich aber mit Stellungnahmen in die Diskussion um Open Access und Open Science ein. Insbesondere Plan S löste Debatten aus (vgl. DMV et al. 2019). Dabei steht die Sorge um die Zukunft des wissenschaftlichen Publikationswesens an erster Stelle.

Weitere Diskursanlässe sind die Transformation fachgesellschaftseigener Publikationen in Open Access (vgl. DGSKA 2021) sowie der Umgang mit (offenen) Forschungsdaten (vgl. DGfE 2017; DGfE/GEBF/GFD 2020; DGV 2018; Schönbrodt/Gollwitzer/Abele-Brehm 2017; Abele-Brehm et al. 2017; Gollwitzer et al. 2018, 2021). Letzteres zeigt auch, wie fachwissenschaftliche Selbstverständigungsprozesse von außen evoziert werden, hier durch die Aufforderung der DFG, disziplinäre Richtlinien im Forschungsdatenmanagement zu formulieren (vgl. DFG 2015).

Trotz dieser zahlreichen Einzelinitiativen bleibt festzustellen, dass sich die Fachgesellschaften insgesamt – von einigen bedeutsamen Ausnahmen abgesehen – eher wenig sicht- und hörbar in die Diskussion und Aushandlung von Open Access in Deutschland eingebracht haben. Unter den rund 750 Unterzeichner*innen der Berliner Erklärung von 2003 sind zahlreiche Universitäten und Forschungseinrichtungen aber nur vier Fachgesellschaften (Stand: 28. Juni 2022). Die Gelegenheit, die Open-Access-Transformation als Anlass zu nutzen, um wissenschaftliche Standards vor dem Hintergrund eines grundlegenden Wandels von Wissenschaft durch die Digitalisierung innerhalb der eigenen Fachcommunity zu diskutieren und damit diese Transformation aktiv mitzugestalten (vgl. z.B. Ganz 2020), wird bislang nur in wenigen Fachgesellschaften aktiv ergriffen. Das überrascht, da Fachgesellschaften Orte der Selbstorganisation und der Selbstverständigung fachlicher Communities sind (vgl. Wissenschaftsrat 1992). Finden in den Fachcommunities keine Diskussionen über Open Access und Open Science statt oder sind diese lediglich nicht sichtbar, weil sie nicht in öffentlichen Stellungnahmen münden? In jedem Fall bleibt festzustellen, dass die Entwicklung des Themas Open Access in den Fachgesellschaften noch viel Potential besitzt. „Fachcommunities könnten eine Vorreiterrolle einnehmen“, sagte ein Teilnehmende in Hinblick auf die gegenwärtige Situation und benannte damit sowohl die Chancen als auch die Herausforderungen der wissenschaftsnahen Entwicklung des Themas Open Access.

Im Anschluss an diese Gegenwartsdiagnose wurden in unserem Workshop folgende Handlungsfelder identifiziert:

- Die Ausgestaltung des wissenschaftlichen Publikationswesens in der Open-Access-Transformation (Geschäftsmodelle, Finanzierung, Publikationsformate).

- Qualitätssicherung, wissenschaftliche Anerkennungsverfahren und Reputationssysteme

- Die Definition der Rolle fachwissenschaftlicher Communities in der Open-Access-Transformation als Vertreter*innen und Sprachrohr ihrer Community in Governance-Prozessen.

Aus diesen Handlungsfeldern wurden im Anschluss in Arbeitsgruppen weitere Fragen, Maßnahmen und Empfehlungen abgeleitet:

Reputationssysteme

Ausgangspunkt der Diskussion in einer der beiden Arbeitsgruppen war die Beobachtung, dass Wissenschaftler*innen in erster Linie in möglichst angesehenen Zeitschriften und Verlagen publizieren wollen. Open Access sei demgegenüber eine nachgeordnete Frage, es bestünden zum Teil Vorbehalte bezüglich der Qualität. Angesichts des starken Drucks, sich durch Artikel in High Impact Journals zu etablieren, bleibe Open Access ein marginales Thema. Damit Open Access mehr Gewicht bekomme, müsse das Reputationssystem reformiert werden. Ob und wie Fachgesellschaften diesbezüglich eine Rolle übernehmen können, diskutierte die eine Arbeitsgruppe intensiv, während in der anderen Arbeitsgruppe die Meinung vorherrschte, dass Wissenschaftler*innen und ihre Organisationen selbst diese Veränderung aktiv betreiben müssten.

Die Bedeutung der Monographie

Ein wichtiger Faktor in der Open Access-Transformation ist insbesondere für die Vertreter*innen von geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Fachgesellschaften die Bedeutung der Monographie. Bisher lagen die Schwerpunkte konsortialer Transformationsabkommen aber im Bereich der Zeitschriften. Mit Blick auf die Entwicklungspotentiale der Transformation des Monographienmarktes wurde unter anderem diskutiert, welche Rolle Verlage im Bereich der Qualitätssicherung haben. Bei genauerem Hinsehen, so die vorherrschende Meinung, seien es aber nicht ausschließlich die Verlage, die Qualität sichern, sondern häufig im selben Maße die Herausgeber*innen, die mit ihrem Namen für Qualität einstehen. Bemerkt wurde zusätzlich, dass Mittel für Open-Access-Bücher oft knapp seien. So stellte sich abschließend die Frage, welche fairen Lösungen für eine Finanzierung entwickelt werden können. Müssten Fachgesellschaften letztendlich selbst Repositorien und andere Infrastrukturen für die Publikation von Monographien aufbauen? Letzteres sei kaum leistbar. Als möglicher Weg, sich als Fachgesellschaft einzubringen, wurde schließlich die Publikation eigener Open-Access-Buchreihen benannt, die durch anerkannte Wissenschaftler*innen eines Fachgebietes herausgegeben werden.

Best Practices

In Bezug auf die eigene Rolle als Herausgeber*in von Zeitschriften wurden positive Erfahrungen und Handlungsmöglichkeiten geteilt: so durchläuft die Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Kulturanthropologie (DGSKA) aktuell einen Transformationsprozess: auf APCs wird dabei verzichtet, die Finanzierung der Zeitschrift erfolgt durch die Fachgesellschaft, deren Mitglieder an der Entscheidung über die Umstellung beteiligt wurden und diese überwiegend positiv aufnehmen. Dies zeigt, dass jenseits von APCs auch andere Geschäftsmodelle möglich sind, z.B. durch konsortiale Finanzierungen, wie sie etwa in der Open Library of Humanities praktiziert oder in KOALA angestrebt werden. Über diese unterschiedlichen Möglichkeiten müsse das Bewusstsein bei den Autor*innen deutlich gestärkt werden.

Anreize zur Offenheit

Um eine Kultur der Offenheit im Publikationswesen – und dort insbesondere in der Qualitätssicherung – zu fördern, bedarf es also häufig einer verstärkten Informationsinitiative unter den Mitgliedern. Der Kenntnisstand zum Thema Offene Wissenschaft ist je nach Fachkultur unterschiedlich stark ausgeprägt. Einige Teilnehmende sprachen diesbezüglich auch von einem Generationenkonflikt unter den Mitgliedern, wobei jüngere Wissenschaftler*innen oft aufgeschlossener gegenüber Open Science und Open Access seien. Anreizsysteme können in einer solchen Situation den Kulturwandel befördern.

Ideen und Vorschläge für ein stärkeres Commitment zu offener Wissenschaft gab es viele in der Diskussion; teilweise wurde auf bereits praktizierte Maßnahmen hingewiesen. Insgesamt entstand auf diese Weise ein umfassendes Bild bereits existierender und geplanter Leistungen der Fachgesellschaften im Feld Open Access. Genannt wurde die Einrichtung von Publikationsfonds durch Fachgesellschaften, das Aussprechen von Empfehlungen für Qualitätskriterien für Zeitschriften oder die Vergabe von Preisen für Open-Access- und Open-Science-Projekte. Auch die Entwicklung von Konzepten für den Umgang mit personenbezogenen Daten sowie von Ethik-Leitlinien für Forschungsdaten könne Anreize für den Kulturwandel hin zu mehr Offenheit setzen.

Synergien schaffen

Im Allgemeinen äußerten viele den Wunsch, Konzepte und Leitlinien gemeinsam zu erarbeiten, denn finanzielle und personelle Ressourcen seien auch in den Fachgesellschaften knapp. Der Wunsch, Publikationsinfrastrukturen übergeordnet zu finanzieren, wurde mehrfach zum Ausdruck gebracht.

Gerechtigkeits- und Nachhaltigkeitsfragen

Diskutiert wurde auch, dass inzwischen zwar viele reputationsreiche Zeitschriften open access seien, die von ihnen verlangten Article Processing Charges stellten jedoch ein Problem für Autor*innen außerhalb gut ausgestatteter Forschungseinrichtungen dar. Deshalb stelle sich die Frage, wie nachhaltig die Finanzierung von APC/BPC-basiertem Open Access angesichts steigender Kosten und Publikationszahlen sein könne. Im Rahmen der DEAL-Verträge werden auch Open-Access-Publikationen in hybriden Zeitschriften finanziert. Davon profitieren z.T. auch Fachgesellschaften, die Herausgeber wissenschaftlicher Journals sind, wie die anwesende Gesellschaft deutscher Chemiker (GDCH). Doch auch dieses Modell wird kritisch diskutiert (vgl. Oberländer/Tullney 2021).

Die Rolle der Politik und der Forschungsförderer

Bezüglich der Empfehlungen an die Politik äußerten die Teilnehmenden den Wunsch, dass Forderung und Förderung (beispielsweise durch die Entwicklung vorhandener Infrastruktur) Hand in Hand gehen müssten: Teilweise sei es so, dass Fördereinrichtungen Vorgaben machten, während gleichzeitig die notwendigen (finanziellen und technischen) Rahmenbedingungen, um diese zu erfüllen, nicht bestünden. Hier sei erforderlich, dass mehr Rückkopplung stattfinde. Überhaupt sei es wünschenswert, dass Fachgesellschaften analog zur Nationalen Forschungsdaten-Infrastruktur (NFDI) auch im Bereich Open Access an einer Koordinationsstelle beteiligt seien. Hilfreich wäre es auch, wenn Verantwortliche in Politik und Fördereinrichtungen Checklisten aufstellten, anhand derer Open-Science-Standards abgeglichen und entwickelt werden könnten. Grundlegend müsse es darum gehen, Nachhaltigkeit im Wissenschaftssystem zu garantieren und transparente Kostenmodelle für das Publikationswesen zu entwickeln.

Die Rolle der Fachgesellschaften in der der Transformation

Immer wieder wurde im Laufe des Workshops das Selbstverständnis der Fachgesellschaften im Prozess der Transformation thematisiert. Brauchen (kleine) Fachgesellschaften angesichts der Open-Access-Transformation eine Strategie? Zumindest stellte sich die Frage, wie sie ihre Rolle angesichts der grundlegenden Veränderungen im Wissenschaftssystem (neu) definieren. Dies kann bedeuten, eine wissenschaftspolitische Rolle einzunehmen oder wiederzuentdecken. Zunächst ginge es aber, so einige der Anwesenden, darum, einen Überblick über die Entwicklungen im eigenen Fach zu erlangen und eine eigene Expertise zu entwickeln, um dann einen Verständigungsprozess mit den Mitgliedern anzustoßen. Zur Diskussion stand somit auch, wie Beteiligungs- und Verständigungsprozesse gestaltet werden könnten. Ferner wurde wiederholt diskutiert, ob Fachgesellschaften in der Lage seien, selbst verlegerisch tätig zu werden und welche administrativen und technischen Fragen sich daraus ergeben würden?

Den Abschluss des Workshops bildete der Ausblick auf den weiteren Projektverlauf. Dabei wurden die Teilnehmer*innen eingeladen, sich an einem im Herbst geplanten Strategieworkshop anlässlich des Projektabschlusses weiter an der Diskussion zu beteiligen. Dieser Aufforderung nachkommen zu wollen, erklärten sich in einer abschließenden Umfrage alle Anwesenden bereit.

Literaturangaben

- Abele-Brehm, Andrea; Antoni, Conny; Bölte, Jens; Gollwitzer, Mario; Hellmann, Deborah; Horz, Holger; Schönbrodt, Felix; Schröder, Annette; Spinath, Birgit (2017). „Kommentar des Vorstands der DGPs und der Autoren der Empfehlungen zum Kommentar des Fachkollegiums Psychologie und der Geschäftsstelle der DFG zu den Empfehlungen des DGPs-Vorstands zum Umgang mit Forschungsdaten“ In: Psychologische Rundschau, Jg. 67, 1, S. 36-38.

- Arbeitsstelle kleiner Fächer (2020). „Dokumentation des Informations-und Vernetzungsworkshops Digitalisierung in Lehre und Forschung kleiner Fächer“. https://www.kleinefaecher.de/beitraege/blogbeitrag/dokumentation-des-informations-und-vernetzungsworkshops-digitalisierung-in-lehre-und-forschung-kle.html (Zugriff: 31. Mai 2022)

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (2015). „Leitlinien zum Umgang mit Forschungsdaten“. https://www.dfg.de/download/pdf/foerderung/grundlagen_dfg_foerderung/forschungsdaten/leitlinien_forschungsdaten.pdf (Zugriff: 30. Mai 2022)

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft (DGfE); Gesellschaft für empirische Bildungsforschung (GEBF); Gesellschaft für Fachdidaktik (GFD) (2020). „Empfehlung zur Archivierung, Bereitsstellung und Nachnutzung von Forschungsdaten in den Erziehungs- und Bildungswissenschaften und Fachdidaktiken“. https://www.dgfe.de/fileadmin/OrdnerRedakteure/Stellungnahmen/2020.03_Forschungsdatenmanagement.pdf (Zugriff: 30. Mai 2022)

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft (DGfE) (2017). „Stellungsnahme der DGfE zur Archivierung, Bereitstellung und Nachnutzung qualitativer Forschungsdaten in der Erziehungswissenschaft“. https://www.dgfe.de/fileadmin/OrdnerRedakteure/Stellungnahmen/2017.09_Archivierung_qual._Daten.pdf (Zugriff: 30. Mai 2022)

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sozial-und Kulturanthropologie (DGSKA) (2021). „Die ZfE/JSCA auf dem Weg zum Open Access“. https://www.dgska.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Open_Access_InfoText-Mitglieder.pdf (Zugriff: 31. Mai 2022)

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Volkskunde (DGV) (2018). „Positionspapier zur Archivierung, Bereitstellung und Nachnutzung von Forschungsdaten“. https://www.d-g-v.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/dgv-Positionspapier_FDM-1.pdf (Zugriff: 30. Mai 2022)

- Deutsche Mathematiker Vereinigung (DMV), Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft (DPG), Dachverband der Geowissenschaften (DVGeo), Gedellschaft deutscher Chemiker (GDCH), Verband Bio, Biowissenschaften und Biomedizin in Deutschland (VBio) (2019). „Plan S. Joint statement of learned societies in mathematics and science in Germany“. https://wissenschaft-verbindet.de/gemeinsame-aktivitaeten/download/190208_plan-s_fin.pdf (Zugriff: 31. Mai 2022)

- Ganz, Kathrin (2020). „Die Open-Access-Politik des Plan S: Eine Chance für Publikationsmodelle im Dienst der Wissenschaft“. https://www.soziopolis.de/die-open-access-politik-des-plan-s/dossier-open-access.html (Zugriff: 30. Mai 2022)

- Gollwitzer, Mario; Abele-Brehm, Andrea; Fiebach, Christian J.; Ramthun, Roland; Scheel, Anne; Schönbrodt, Felix; Steinberg, Ulf / DGPs-Kommission ‚Open Science‘ (2021). „Management und Bereitstellung von Forschungsdaten in der Psychologie. Überarbeitung der DGPs-Empfehlungen“ In: Psychologische Rundschau, Jg. 72,2,S.132-146.

- Gollwitzer, Mario; Schönbrodt, Felix; Abele-Brehm (2018). „Die Datenmanagement-Empfehlungen der DGPs. Ein Zwischenstand“ In: Psychologische Rundschau, Jg. 69,4, S. 366-373

- Oberländer, Anja; Tullney, Marco (2021). „Gemeinschaftliche Open-Access-Finanzierung als Aufgabe für Bibliotheken“ DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4730883

- Schönbrodt, Felix; Gollwitzer, Mario; Abele-Brehm, Andrea (2017). „Der Umgang mit Forschungsdaten im Fach Psychologie. Konkretisierung der DFG-Leitlinien. Im Auftrag des DGPs-Vorstands (17.9.2016)“ In: Psychologische Rundschau Jg. 68, 1, S. 20-35

- Severin, Anna; Egger, Matthias; Eve, Martin Paul; Hürlimann, Daniel (2020). „Discipline-specific open access publishing practices and barriers to change: an evidence-based review (Version 2)“. DOI: 10.12688/f1000reserch.17328.2

- Wissenschaftsrat (1992) „Zur Förderung von Wissenschaft und Forschung durch Fachgesellschaften“. https://www.wissenschaftsrat.de/download/archiv/0823-92.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (Zugriff: 31. Mai 2022)