French Colonialism in Indochina

Thi Trang Ha Nguyen (SoSe 2025)

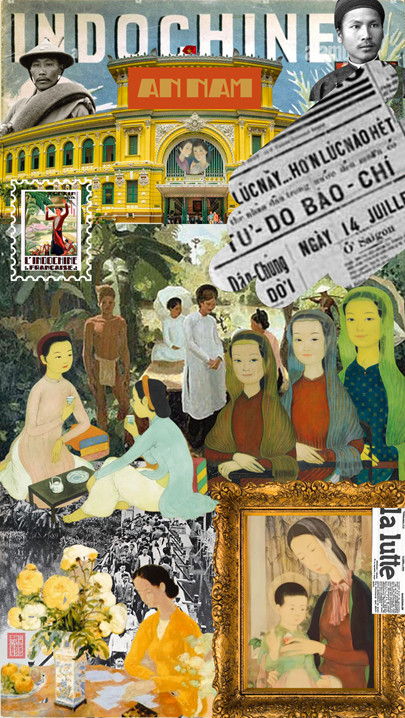

Illustration 1. Art as Colonial Resistance

1. Introduction

Through this essay and my collage, I seek to tell a part of my country’s colonial history—a history you may not have encountered before, or that might echo experiences of other colonized nations. Yet, as a Vietnamese, I feel compelled to narrate this story myself, from the perspective of a generation that still lives close to those memories. My great-grandparents and grandparents lived through French colonial rule and fought for independence; my parents grew up under its lingering influence while also resisting those cultural impositions. My generation has been described as the last that will have direct access to war veterans and witnesses of that period, people whose stories still bridge the past and present.

This project is also an intervention in what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has described as “the danger of a single story”—the risk of reducing complex histories to simplified narratives of domination and passivity.[1] Colonial archives and French accounts of Indochina have long presented such one-sided versions of Vietnamese history. In contrast, my collage seeks to recover and reframe voices, images, and symbols that speak of resilience, resistance, and cultural transformation, situating Vietnamese identity within a broader conversation on colonialism and its legacies.

The collage “Art as Colonial Resistance” (Illutration 1) is not just a collection of visual elements but a deliberate presentation of a view. It presents a combination of Vietnamese artworks by Lê Phổ, Mai Trung Thứ, and Lê Thị Lựu, along with colonial-era images, newspaper clippings, and fragments from French Indochina. The visual composition enables me to examine how art evolved into an understated form of rebellion alongside cultural preservation tools and colonial resistance mechanisms.

2. Visual Layers of Resistance: Reading the Collage

To analyze the visual and symbolic elements of my collage, ‚Art as Colonial Resistance,‚ Stuart Hall’s idea of representation provides a strong theoretical framework for understanding the visual elements used in the collage. In his view, “representation is not a passive reflection of reality, but an active process that constructs meaning within a social and political context”. Meaning is produced through language, images, and cultural codes, and is shaped by who holds power over that production. In colonial contexts, representation becomes a tool of domination: the colonizer defines the colonized subject, culture, and history in ways that sustain colonial rule. Hall believes that resistance is possible by disrupting these representations, reappropriating symbols, and creating new meaning. This is especially relevant to the field of visual art, where images both reflect and shape ideologies. Applied to colonial Vietnam, this means that while French art institutions encoded European techniques, Vietnamese artists re-decoded them by painting traditional themes on silk, giving new meaning to borrowed forms.

I will analyze the collage from top to bottom, from left to right. The top portion of the collage displays a French newspaper headline that announces „Indochine“. At the same time, this term consolidated Vietnam with Cambodia and Laos under a single colonial name that erased their unique cultural identities.[2] The term „Annam“ appears above the Saigon Central Post Office – designed by Gustave Eiffel, which is located below the headline „Indochine“ – started as a reference to Vietnam, and colonial authorities used it to label Vietnamese individuals as „Annamites“ while keeping racist and hierarchical elements intact. To call someone Annamite was not just to refer to their origin but to locate them within a hierarchy that justified colonial domination and racial inferiority.

A Vietnamese soldier appears in the left section wearing both a nón lá hat[3] and a French military uniform as a member of the French colonial army’s lính tập[4] conscripted force. Most of these soldiers originated from rural regions before being forced to serve in the position of enforcing French colonial control over their fellow Vietnamese citizens while being treated as second-class subjects by their French superiors. The dual nature of colonial identity becomes visible through this representation because resistance and cooperation frequently coexisted.

The right side of the collage features a portrait of Emperor Hàm Nghi, one of the last sovereigns of the Vietnamese Nguyễn dynasty before French domination, who refused to submit to French control. French authorities took him into captivity before deporting him to Algeria, where he spent 56 years in exile, not allowing him to return to Vietnam even after his death. Despite his exile, Hàm Nghi never relinquished his identity—he continued to wear traditional Vietnamese garments, braided his hair in the old style, and raised his children to speak Vietnamese and cherish the customs of a country they would never see. The inclusion of both the soldier and the emperor demonstrates how colonialism fragmented the Vietnamese identity, which expressed both forced submission and active resistance through personal actions.

2.1. Colonial Gaze vs. Vietnamese Self-Representation

Continues to the middle section of the collage features Haiphong[5] (Illustration 2), a painting by French artist Gaston Roullet. The scene Gaston Roullet painted depicts a jungle landscape with figures dressed in áo dài[6], mostly women, casually drinking tea or chatting under the trees. What seems idyllic at first glance becomes more troubling on closer inspection: a male figure in tribal clothing stands off to the side, gazing outward beyond the frame, and, though not visible in my collage, a naked boy playing on the ground in the foreground of the painting. The man in tribal garb, with his bare legs, woven sash, and bare chest, adds to the imagined „wildness“ of the Indochinese environment. A further noticeable presence is the background or the scenery of the painting. All the figures are gathered and placed in the middle of a jungle, next to a river or a lake, and not in the garden of a house, or even a community yard. Though the scenery might truly be from a rural village, the French colonial perspective, as depicted in this artwork, is typical of Orientalist stereotypes, presents Vietnam as an inactive and exotic territory, reinforcing the colonial narrative of European superiority and the ‚otherness‘ (footnote about Bhabha’s theory) of non-Western cultures: wildest, uncivilised and dynamic.

Illustration 2. Gaston Roullet, Haiphong, source: Saigoneer.

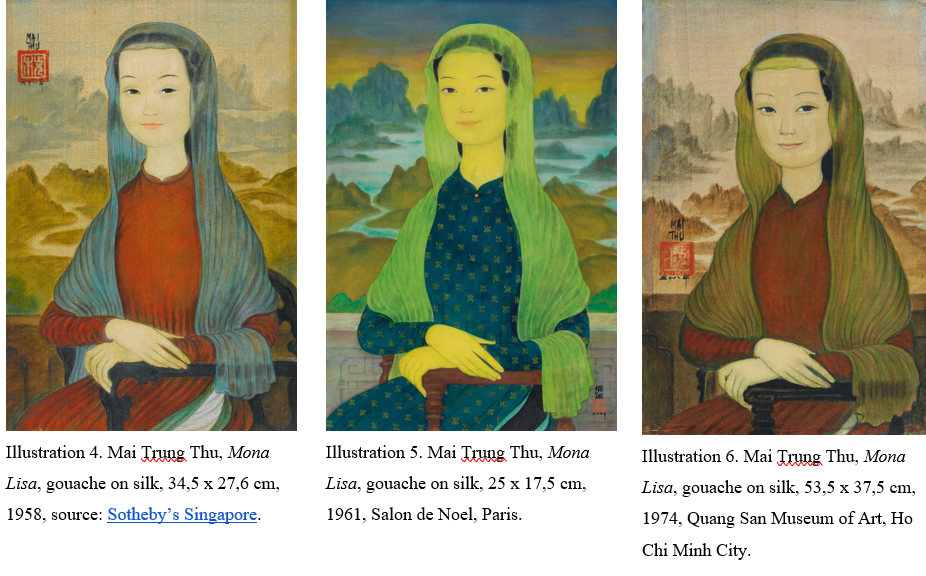

Gaston Roullet’s artwork contrasts with that of Mai Trung Thứ,[7] a Vietnamese artist who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine (the Indochina College of Fine Arts). The artist Mai Trung Thứ employed European artistic methods to portray Vietnamese people with both respect and a deep personal connection. With the same context of enjoying tea and chatting between women, Mai Trung Thứ’s female figures in the painting The tea time (Illustration 3) are depicted in a close-up view facing one another. Their facial features are also more visible and vibrant than those in Haiphong. The female figures both wear the traditional áo dài, both in pastel colors – one pink and the other blue – and are resting, leaning on gối trái dựa[8] cushion while enjoying tea. In this artwork, it is clear that the artist demonstrates both cultural continuity and national pride. Besides these two figures, there are three female figures, drawn from separate paintings of the same woman by Mai Trung Thứ (Illustration 4-6), depicting women wearing áo dài, accompanied by khăn voan[9] and khăn vấn[10]headscarves, which represent the femininity of women from the upper class of the Red River Delta region. While their poses and every placement of gestures, clothing, and scenery recreate the frontal symmetry of the famous Mona Lisa, their attire is distinctly Vietnamese in style. Their eyebrows are finely arched, and their eyes are almond-shaped, capturing a Vietnamese ideal of beauty that differs from European portrait norms. While Gaston Roulette’s depiction is filtered through a colonial gaze, rendering women as decorative ethnographic objects within an exoticized landscape, Mai Trung Thứ female figures exude an inner aura and dignified calmness that can only be seen in high-class women. They dressed in elegant áo dài with high-quality headwear, surrounded by gentle scenes featuring traditional motifs often found in classical East Asian scroll paintings, which emphasized harmony and serenity.

Below these figures is a painting by Lê Phổ[11], titled The Present from Mother (Illustration 7), in which he reimagined the Madonna and Child composition by integrating Christian symbols into Vietnamese clothing and cultural aspects, while maintaining local cultural expressions. The mother figure wears a simple black áo tứ thân[12] and brown áo dài with a white khăn vấn wrapped in layers. In contrast, her child wears a yếm (a traditional baby vest). The mother’s gentle posture, hand on the child’s back, and slightly leaning forward express Vietnamese maternal tenderness — subtle but deeply emotional. This reinterpretation not only domesticated the foreign iconography but also rooted it back into Vietnamese familial values and aesthetics. Through these artworks, I explore how Vietnamese artists, particularly Mai Trung Thứ and Lê Phổ, challenged the colonial image of „Annam“ not through violent resistance but through aesthetic subversion. They accepted the tools of European art rather than transforming them, but only to use them as a tool to visualise “annamites” beauty, tradition, and culture. In their hands, brushstrokes, the use of colours, highlights, and shadows became a reclamation of beauty, of identity, of dignity. By dressing their figures in fabrics, scarves, and silhouettes rooted in Vietnamese history, they offered viewers a counterimage: one that did not need validation from the colonial gaze.

Illustration 3. Mai Trung Thu, The tea time, Ink and gouache on silk laid onto cardboard, source: Sotheby’s Hong Kong.

Illustration 7. Le Pho, The present from mother, ink and colour on silk, 50,5 x 63,5 cm, ca. 1935-1945, source: V.artview.

2.2. Cultural Memory and Continuity Through Art

The Impressionist painting by Lê Phổ, located in the lower left corner, is another depiction of a woman wearing an áo tứ thân as she sits in contemplation, and is titled „The Beauty in a Sunshine Shirt“ (Illustration 8). Lê Phổ’s use of light and texture – impressionistic yet restrained – seems to preserve an intimate memory of Vietnam, untouched by colonial spectacle: soft and dreamlike. The brushwork does not impose narrative; it allows for emotion and cultural interiority. The pattern of the flower vase and the fruit plate is a traditional Vietnamese motif commonly found on ceramic and porcelain wares, especially those rendered in blue ink on a white porcelain base. Common motifs include mythical animals, such as the dragon, phoenix, or carp, as well as floral arrangements. Lê Phổ applied modernist artistic methods to preserve emotional and cultural heritage rather than conforming to colonial tastes.

Illustration 8. Le Pho, The beauty in a ‘sunshine’ shirt, source: hanoitimes

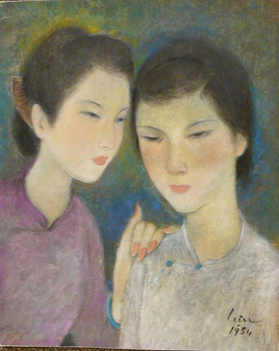

Further up on the Saigon Central Post Office is a circular frame in the center-right section of the collage, which showcases the artwork of Lê Thị Lựu, who became one of the leading female painters of her generation. Her painting Nhị kiều (Illustration 9) depicted female characters from Truyện Kiều[13]. The subjects embody Confucian virtues and national literary themes through their modern áo dài attire and makeup, as well as their body language and facial expressions. Thúy Kiều wears a purple áo dài, while Thúy Vân wears one in ash gray. The two sisters possess a unique blend of Chinese-Vietnamese beauty, characterized by slightly slanted almond-shaped eyes and an oval face. Their hair is styled in a bare coiled bun, revealing elegant, long necks reminiscent of Hà Nội’s beauties in the 1930s–1940s. The rounded framing, resembling a medallion or memory locket, reinforces their symbolic status as protectors of cultural identity. This circular motif also overlaps with the Saigon Central Post Office, a colonial architectural landmark. In doing so, it visually suggests that even within colonial structures – both physical and ideological – Vietnamese culture persists, encoded in literature, art, and feminine imagery.

Illustration 9. Le Thi Luu, Nhị Kiều, silk mounted on paper, 41,5 x 33,4 cm, 1954, source: tapchimythuat

2.3. Women as Keepers of Cultural Identity

Picture 1. Photograph of a bridge across Hoàn Kiếm Lake to Ngọc Sơn Temple in Hanoi. Source: Dannaud, J. P., L’Indochine Profonde, 1954.

In the collage, near the left edge and as the background of Lê Phổ’s painting, is a sepia-toned colonial photograph of Hanoi (Picture 1), depicting, at first glance, it appears like a typical street scene – but a closer look reveals the men wearing Western attire and sporting European hairstyles as they demonstrate their assimilation into colonial culture. In contrast, the women retain traditional áo dài, wear their hair long and parted or wrapped in scarves, and move with a grace that seems untouched by the colonial world growing around them. This gendered visual dichotomy is no coincidence — it reflects a broader cultural tension that ran through colonized Vietnam. The French colonial regime targeted Vietnamese men through the education system, political co-optation, and economic roles. They were expected to assimilate into French modernity: to speak the language, adopt the style, and embody the „civilizing mission“ on the surface. Meanwhile, women were often left out of this assimilation project — either deliberately excluded or silently resisting — and thus became the carriers of tradition in both public image and private life. This is why so many Vietnamese artists of the colonial period chose to depict women and children.

These depictions should not be misunderstood as passive or apolitical. They represent a quiet, visual form of resistance. At a time when the colonial state was reshaping the identity of Vietnamese men, these images of women stood as emblems of cultural continuity. They were not merely aesthetic subjects — they were symbols of national memory, protectors of the intangible customs being threatened with erasure. By drawing attention to these gendered dynamics, my collage highlights how resistance can manifest in various forms — not just in protests or armed struggle but also in choices about what to paint, how to dress, and which memories to preserve. In the face of violent change, Vietnamese women — and the artists who painted them — offered the country something quietly powerful: the reassurance of something deeply familiar.

2.4. Words as Weapons: Print Culture and the Politics of Language

In the collage lie two critical fragments from the historical newspaper La Lutte and Dân Chúng. The clipping of La Lute is in the lower right of the collage, and the clipping of Dân Chúng is in the upper right corner. Though small in size, their symbolic weight is immense. They speak to a war fought not only with weapons but with words, language, and the right to speak freely.

La Lutte, meaning „The Struggle,“ was a revolutionary French-language newspaper published during the 1930s. At first glance, the use of the colonizer’s language might seem paradoxical. However, its existence highlights the complexity of colonial domination and resistance. Under French rule, Vietnamese students were forbidden to learn Han-Nôm, the traditional writing system that had long been used in Vietnam’s court and literary culture. Instead, French language and culture were imposed through schools, street signs, administrative documents, and even the names of cities and public squares. La Lutte was written in French, but using the very language that sought to erase Vietnamese identity to denounce injustice and call for independence: adopting the colonial voice not to assimilate but to undermine it.

Alongside this sits a fragment from the Vietnamese-language newspaper Dân Chúng („The People“), which published calls for democratic freedoms and labor rights. The visible headline in the collage reads: “Lúc này … Hơn lúc nào hết!” („Now or never!“) and “TỰ-DO BÁO-CHÍ” – a bold declaration for the freedom of the press, of speech, of thought. This is not merely a cry for abstract ideals; it is a historical demand, shouted under the surveillance of colonial censorship. Crucially, it is written in quốc ngữ, the modern Vietnamese writing system developed in the 17th century by missionaries but later transformed by Vietnamese intellectuals into a powerful tool of communication and national awakening.

By layering these newspaper pieces into my collage, I wanted to honor this history of resistance through literacy. These were not just publications; they were lifelines. They show us that colonialism was not only resisted on battlefields but also in classrooms, on street corners, in art and painting, and inside the cramped printing presses of underground journalists. In a world where every Vietnamese word was policed, every publication was an act of courage.

3. Conclusion

In reflecting on this essay and the collage I created, I have come to see how deeply colonial histories are woven into everyday life—even when they remain invisible or unacknowledged. While working on our group presentation in the Decolonize! seminar about the Ermelerhaus, the Friedrichsgracht, and the Deutsches Kolonialhaus, I was surprised by how much evidence of colonial history surrounds us in Berlin, yet so little information about these legacies is publicly available. This realization made me more attentive to how colonial traces endure not only in archives but also in urban landscapes, architecture, and cultural memory.

The Vietnamese case that my collage engages with demonstrates a similar persistence. The French-built École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine was originally an attempt to colonize Vietnamese art and culture, imposing European techniques and aesthetic values. Yet, artists such as Lê Phổ, Mai Trung Thứ, and Lê Thị Lựu appropriated those techniques to paint Vietnamese textures, themes, and cultural life, thereby transforming a colonial tool into a site of resistance and hybridity. This process mirrors Stuart Hall’s idea that cultural identity is not fixed but is constantly being negotiated and re-articulated through history, power, and representation.

Beyond the realm of art, the presence of colonial architecture remains visible in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, where Indochine buildings and interior design have become a distinctive part of Vietnamese identity. What was once a colonial imposition has been reimagined, re-appropriated, and integrated into cultural expression—demonstrating again how colonial legacies can be subverted and given new meaning.

Through the seminar, the collage, and this writing process, I have realized that decolonial work is less about “erasing” colonial traces than about critically engaging with them: uncovering silenced histories, making their structures visible, and recognizing how marginalized voices transform them into acts of resilience and creativity. This essay has therefore been both an academic and a personal journey, linking my own heritage and memories of Vietnam to broader questions of how colonialism continues to shape—and be challenged in—our everyday lives.

Bibliography

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

Brettell, Caroline B. 1945. “French Indo-China: Demographic Imbalance and Colonial Policy.” Population Index 11, no. 2 (1945): 68–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/2730333.

Hall, Stuart. 1997. “The Work of Representation” in REPRESENTATION: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. SAGE Publisher. https://eclass.aueb.gr/modules/document/file.php/OIK260/S.Hall%2C%20The%20work%20of%20Representation.pdf.

Said, Edward W. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage.

[1] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, The Danger of a Single Story, TED Talk, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg.

[2] The French had three different pronouns to indicate Vietnam|s territories: Tonkin China as Northen Vietnam, Annam as Central Vietnam, and Cochin China as Southern Vietnam, but the term “Annam” was later on widely used to indicate Vietnam. Besides these three ‘countries’ that the French administered in the French Indochina, there were also Combodia and Laos. (“French Indo-China”, p. 68-69)

[3] Is a traditional Vietnamese conical hat made of palm leaves. It serves as both a practical item, protecting the wearer from sun and rain, and a cultural symbol of Vietnam.

[4] were soldiers of several regiments of local ethnic Indochinese infantry organized as Tirailleurs by the French colonial authorities (“Tirailleurs indochinois”, Wikipedia, last modified June 20, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tirailleurs_indochinois)

[5] Name of a port city and industrial center in north Vietnam during the French Colonize. Nowadays, Hai Phong still holding the same important position in Vietnam’s economic and trade.

[6] Vietnamese traditional and national garment

[7] He was one of the four most important painters of Vietnamese modern art that worked and lived in Europe – the Phổ-Thứ-Lựu-Đàm. He was one of the graduates of the first class of the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine. He is famous for his silk painting with gouache about Vietnames women, children, scenery, and architecture. (Mai Trung Thứ, Wikipedia, last modifined June 20, 2025, https://vi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mai_Trung_Th%E1%BB%A9)

[8] Leaning pillows (also known as gối xếp or gối tựa) is a traditional Vietnamese cushion made of 4–5 stacked pillow layers, used for back, arm, or head support when sitting on the floor. Popular among royals and scholars in the past, it was essential during activities like reading, reciting poetry, drinking tea, or relaxing. The cover is made of luxurious brocade with imperial motifs, while the firm, box-shaped inner pillows are tightly stuffed for stability and comfort.

[9] Means veil

[10] Vấn tóc refers to a traditional Vietnamese hairstyle in which the hair is neatly twisted and coiled into a bun using a piece of fabric. It looks like hairband or headband. It was commonly worn by women in northern and central Vietnam, especially during the 1930s–1940s, symbolizing elegance and refinement. (Tóc vấn trần, Vietnamese Encyclopedia, last modifined June 20, 2025, https://bktt.vn/T%C3%B3c_v%E1%BA%A5n_tr%E1%BA%A7n)

[11] Lê Phổ was a Vietnamese and internationally renowned master painter known for his romantic style and many highly valued works. Often called the „Vietnamese Master Painter in France,“ he is regarded as a towering figure in Vietnamese art. Lê Phổ is also recognized as one of the „Four Masters in Europe“ of modern Vietnamese painting, alongside Mai Trung Thứ, Lê Thị Lựu, and Vũ Cao Đàm. (Lê Phổ, Wikipedia, last modifined June 20, 2025, https://vi.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%AA_Ph%E1%BB%95)

[12] A traditional dress that was worn widely by women in Nothern Vietnam before the áo dài. Its name means four-pieced shirt with long flowing outer tunic, reaching almost to the floor. It is open at the front, like a jacket. At the waist the tunic splits into two flaps: a full flap in the back (made up of two flaps sewn together) and the two flaps in the front which are not sewn together but can be tied together or left dangling.

[13] Truyện Kiều (The Tale of Kiều) is a Vietnamese epic poem written by Nguyễn Du in the early 19th century. Comprising over 3,200 verses in lục bát (six-eight) meter, it tells the tragic love story of Thúy Kiều, a talented and virtuous young woman who sacrifices herself to save her family, enduring hardship and injustice. The work is celebrated for its poetic beauty, emotional depth, and philosophical reflections on fate, morality, and resilience. Nguyễn Du is considered one of Vietnam’s greatest literary figures, and Truyện Kiều a masterpiece of Vietnamese literature. (Truyện Kiều, Wikipedia, last modified June 20, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tale_of_Kieu)

Quelle: Thi Trang Ha Nguyen, Decolonize! Art as Colonial Resistance – French Colonialism in Indochina, in: Blog ABV Gender- und Diversitykompetenz FU Berlin, 10.12.2025, https://blogs.fu-berlin.de/abv-gender-diversity/?p=527